Clock Case

1756-1757 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The historical information about the Strasbourg factory is from the published work of Dorothée Guillemé Brulon.

This extraordinary faïence (tin-glazed earthenware) clock case was made in Strasbourg at the manufactory of Paul Hannong from about 1754-61. Paul and his brother Balthazar had taken over the pottery following the retirement of their father, Charles-François Hannong in 1732. Charles-François, of Dutch origin, started as a humble pipe manufacturer in the city in 1709 and went on to found a dynasty of three generations producing high quality faience and porcelain. His faïence factory started in 1721 when he joined forces with a German faïencier, Henri Wachenfeld. The following year however, Wachenfeld returned to Germany to establish his own factory at Durlach.

The Strasbourg enterprise went from strength to strength and in 1724 a branch was established 40 kms to the north in Hagenau. By 1737, Charles-François’ eldest son, Paul, was in sole charge of both sites. The continuing success of the factory was assured when between 1745-1748 he perfected the technique of ‘petit feu’ decoration, using a second low temperature firing in a muffle kiln to produce the rich pinks and purples (derived from purple of Cassius) for which Strasbourg is famed today. The development of this wider palette was essential in order to compete with the new French porcelains being produced and was particularly important for the popular theme of flower painting at this time.

The success of his factory attracted workers from all over Germany. The first notable recruit was the Meissen painter Christian-Wilhelm Lowenfinck in 1748. He was soon followed by his brother Adam-Friederich and his wife Maria-Seraphia, an accomplished painter of flowers and landscapes. Paul Hannong went on to produce hard-paste porcelain in 1751 or 1752 with the aid of the former Meissen chemist, Jacob Ringler. This infringed the monopoly of the Vincennes factory and Hannong was forced to move this side his porcelain production beyond the Rhine to the Palatinate, establishing the Frankenthal factory in 1755.

His new concern obliged Paul Hannong to spend long periods away from Strasbourg, and in addition many of his original staff died or moved away, making it difficult for him to control the quality of the work. In 1754 in an attempt to safeguard his wares from inferior copies, he started to use the PH mark found on this clock. In 1759 Paul died and his two sons took over: Pierre-Antoine at Strasbourg and Hagenau, Joseph at Frankenthal. Pierre-Antoine however, proceeded to sell the secret of hard-paste porcelain production to the French royal factory of Sèvres, an action which provoked his co-legatees (his brother Joseph and his five sisters) to disinherit him. In Frankenthal, after suffering financial difficulties, Joseph sold out to the Elector Karl-Theodore and returned to Strasbourg to assume the direction of both factories.

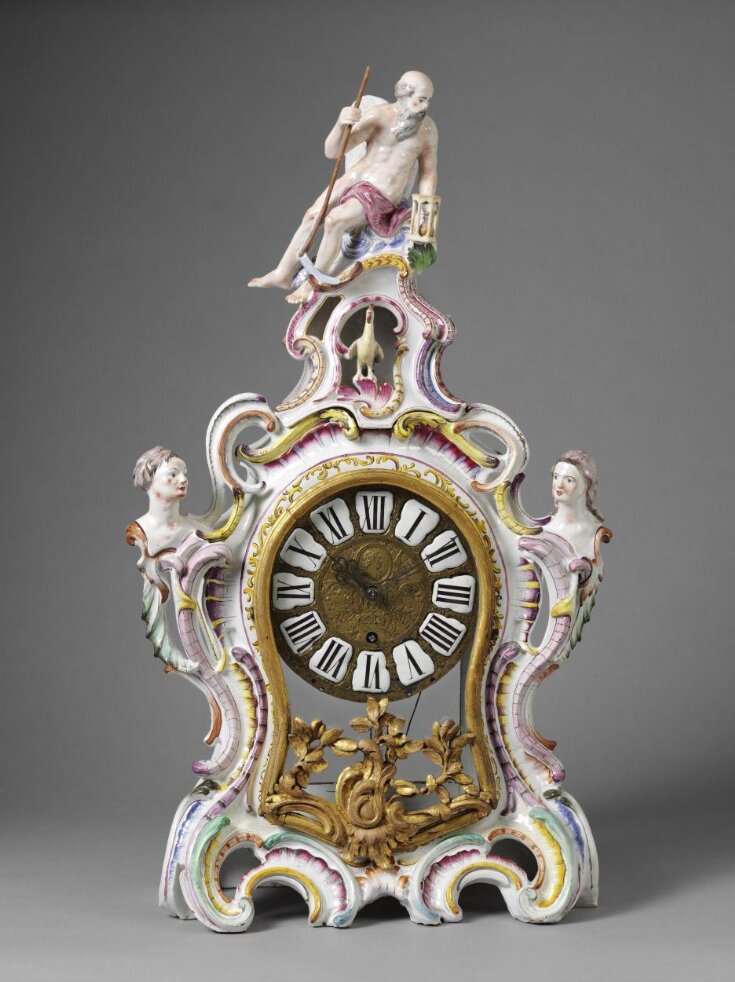

The basic design of this wall clock case takes as its theme the fleeting passage of time, embodied by 'Old Father Time', the standing classical figure at the top holding an hour glass. He is there as a reminder to the young couple, represented by male and female busts, not to dawdle or waste time, while the crowing cockerel in the centre is a further encouragement to 'seize the day'. Allegorical figures of 'Time' and other symbols are often found in gilt-bronze clocks of the late 17th and early 18th century Baroque period, particularly those of the influential cabinet maker and bronze smith André-Charles Boulle. By the 1750s however, lightness, frivolity, asymmetry and colour were all popular design elements in the decorative arts, usually referred to by the term 'Rococo' today. In this clock case, the modeller has shown his mastery of these elements, using the wonderful plasticity of the clay to create bold asymmetrical scrolls and shell-like forms. It is possible he was influenced by the work of local Strasbourg sculptor, Jean-Guillaume Lanz, who is credited with popularising the new style in his work.

This extraordinary faïence (tin-glazed earthenware) clock case was made in Strasbourg at the manufactory of Paul Hannong from about 1754-61. Paul and his brother Balthazar had taken over the pottery following the retirement of their father, Charles-François Hannong in 1732. Charles-François, of Dutch origin, started as a humble pipe manufacturer in the city in 1709 and went on to found a dynasty of three generations producing high quality faience and porcelain. His faïence factory started in 1721 when he joined forces with a German faïencier, Henri Wachenfeld. The following year however, Wachenfeld returned to Germany to establish his own factory at Durlach.

The Strasbourg enterprise went from strength to strength and in 1724 a branch was established 40 kms to the north in Hagenau. By 1737, Charles-François’ eldest son, Paul, was in sole charge of both sites. The continuing success of the factory was assured when between 1745-1748 he perfected the technique of ‘petit feu’ decoration, using a second low temperature firing in a muffle kiln to produce the rich pinks and purples (derived from purple of Cassius) for which Strasbourg is famed today. The development of this wider palette was essential in order to compete with the new French porcelains being produced and was particularly important for the popular theme of flower painting at this time.

The success of his factory attracted workers from all over Germany. The first notable recruit was the Meissen painter Christian-Wilhelm Lowenfinck in 1748. He was soon followed by his brother Adam-Friederich and his wife Maria-Seraphia, an accomplished painter of flowers and landscapes. Paul Hannong went on to produce hard-paste porcelain in 1751 or 1752 with the aid of the former Meissen chemist, Jacob Ringler. This infringed the monopoly of the Vincennes factory and Hannong was forced to move this side his porcelain production beyond the Rhine to the Palatinate, establishing the Frankenthal factory in 1755.

His new concern obliged Paul Hannong to spend long periods away from Strasbourg, and in addition many of his original staff died or moved away, making it difficult for him to control the quality of the work. In 1754 in an attempt to safeguard his wares from inferior copies, he started to use the PH mark found on this clock. In 1759 Paul died and his two sons took over: Pierre-Antoine at Strasbourg and Hagenau, Joseph at Frankenthal. Pierre-Antoine however, proceeded to sell the secret of hard-paste porcelain production to the French royal factory of Sèvres, an action which provoked his co-legatees (his brother Joseph and his five sisters) to disinherit him. In Frankenthal, after suffering financial difficulties, Joseph sold out to the Elector Karl-Theodore and returned to Strasbourg to assume the direction of both factories.

The basic design of this wall clock case takes as its theme the fleeting passage of time, embodied by 'Old Father Time', the standing classical figure at the top holding an hour glass. He is there as a reminder to the young couple, represented by male and female busts, not to dawdle or waste time, while the crowing cockerel in the centre is a further encouragement to 'seize the day'. Allegorical figures of 'Time' and other symbols are often found in gilt-bronze clocks of the late 17th and early 18th century Baroque period, particularly those of the influential cabinet maker and bronze smith André-Charles Boulle. By the 1750s however, lightness, frivolity, asymmetry and colour were all popular design elements in the decorative arts, usually referred to by the term 'Rococo' today. In this clock case, the modeller has shown his mastery of these elements, using the wonderful plasticity of the clay to create bold asymmetrical scrolls and shell-like forms. It is possible he was influenced by the work of local Strasbourg sculptor, Jean-Guillaume Lanz, who is credited with popularising the new style in his work.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 3 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Tin-glazed earthenware painted in enamels |

| Brief description | Clock with case, tin-glazed earthenware, in three parts, the case surmounted by a separately formed figure of Time, Paul Hannong's pottery factory, France, c.1756-1757 |

| Physical description | Case: Clock with case, tin-glazed earthenware, in three parts: bracket and case, the latter surmounted by a separately formed figure of Time. Of rococo scrollwork form, the case with flanked by demi-figures emerging from scrolls. The front of the case has a shaped and glazed door, with applied cast and chased gilt mounts to the lower half. To either side are glazed rectangular panels, with a rectangular opening to the back. Dial: The dial is brass, 21.2cm diameter, cast and chased, with an outer minute ring, numbered 1 to 60 (with flat-topped 8 numerals). The Roman hours are black on white inset plaques of slightly irregular shape. The inner ring of engraved quarter hours are also marked. The centre of the dial has a bust of a cartouche surrounded by trophies, leaves and scrolls, with a crown to the bottom. There is a single winding hole above VI. The hour and minute hands are pierced steel. Movement: The movement plates are 14x10.8cm. The going train has a large going barrel of an estimated 14 day duration, with an intermediate wheel between the great and centre wheels. The escapement is a tic-tac type, with an escape wheel of 30T, the pallets spanning 2T. The pendulum full-length is 27.2cm, with a steel rod and lenticular bob resting on a rating nut. The pendulum hangs from a loop of cord. There is a pull-repeat mechanism on one bell, giving hours, followed by pairs of blows for quarters. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Object history | Bought from the Aigoin Collection When cleaned in 2014 by Francis Brodie, the movement was found to be signed: 'A. Vincent, aux ponts de martel conté de neuf chatel' and on the opposing side dated: 'M11 1757' Les Ponts-de-Martel is today a municipality in the district of Le Locle in the canton of Neuchâtel in Switzerland. |

| Production | Dated by Arthur Lane (French Faïence, 1948, pl. 69) to 1749-60. However, according to Dorothée Guillemé Brulon (Strasbourg & Niderviller - Sources et rayonnement, Histoire de la Faïence Francaise, Paris, 1999, p. 13) the mark was introduced in 1754 and continued to be used after Paul Hannong's death in 1760. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | The historical information about the Strasbourg factory is from the published work of Dorothée Guillemé Brulon. This extraordinary faïence (tin-glazed earthenware) clock case was made in Strasbourg at the manufactory of Paul Hannong from about 1754-61. Paul and his brother Balthazar had taken over the pottery following the retirement of their father, Charles-François Hannong in 1732. Charles-François, of Dutch origin, started as a humble pipe manufacturer in the city in 1709 and went on to found a dynasty of three generations producing high quality faience and porcelain. His faïence factory started in 1721 when he joined forces with a German faïencier, Henri Wachenfeld. The following year however, Wachenfeld returned to Germany to establish his own factory at Durlach. The Strasbourg enterprise went from strength to strength and in 1724 a branch was established 40 kms to the north in Hagenau. By 1737, Charles-François’ eldest son, Paul, was in sole charge of both sites. The continuing success of the factory was assured when between 1745-1748 he perfected the technique of ‘petit feu’ decoration, using a second low temperature firing in a muffle kiln to produce the rich pinks and purples (derived from purple of Cassius) for which Strasbourg is famed today. The development of this wider palette was essential in order to compete with the new French porcelains being produced and was particularly important for the popular theme of flower painting at this time. The success of his factory attracted workers from all over Germany. The first notable recruit was the Meissen painter Christian-Wilhelm Lowenfinck in 1748. He was soon followed by his brother Adam-Friederich and his wife Maria-Seraphia, an accomplished painter of flowers and landscapes. Paul Hannong went on to produce hard-paste porcelain in 1751 or 1752 with the aid of the former Meissen chemist, Jacob Ringler. This infringed the monopoly of the Vincennes factory and Hannong was forced to move this side his porcelain production beyond the Rhine to the Palatinate, establishing the Frankenthal factory in 1755. His new concern obliged Paul Hannong to spend long periods away from Strasbourg, and in addition many of his original staff died or moved away, making it difficult for him to control the quality of the work. In 1754 in an attempt to safeguard his wares from inferior copies, he started to use the PH mark found on this clock. In 1759 Paul died and his two sons took over: Pierre-Antoine at Strasbourg and Hagenau, Joseph at Frankenthal. Pierre-Antoine however, proceeded to sell the secret of hard-paste porcelain production to the French royal factory of Sèvres, an action which provoked his co-legatees (his brother Joseph and his five sisters) to disinherit him. In Frankenthal, after suffering financial difficulties, Joseph sold out to the Elector Karl-Theodore and returned to Strasbourg to assume the direction of both factories. The basic design of this wall clock case takes as its theme the fleeting passage of time, embodied by 'Old Father Time', the standing classical figure at the top holding an hour glass. He is there as a reminder to the young couple, represented by male and female busts, not to dawdle or waste time, while the crowing cockerel in the centre is a further encouragement to 'seize the day'. Allegorical figures of 'Time' and other symbols are often found in gilt-bronze clocks of the late 17th and early 18th century Baroque period, particularly those of the influential cabinet maker and bronze smith André-Charles Boulle. By the 1750s however, lightness, frivolity, asymmetry and colour were all popular design elements in the decorative arts, usually referred to by the term 'Rococo' today. In this clock case, the modeller has shown his mastery of these elements, using the wonderful plasticity of the clay to create bold asymmetrical scrolls and shell-like forms. It is possible he was influenced by the work of local Strasbourg sculptor, Jean-Guillaume Lanz, who is credited with popularising the new style in his work. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 465 to B-1870 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 7, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest