Rapier

ca. 1600 (assembled)

| Place of origin |

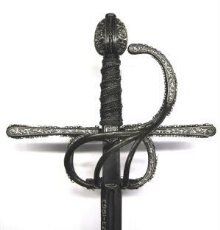

This rapier is composed of a hilt made in France, possibly by Claude Savigny of Tours, who was renowned for encrusting his hilts with silver chains, and a blade made in Toledo, by Francisco Ruiz, who was part of a famous family of bladesmiths.

Rapiers were civilian weapons with long slender blades designed to pierce clothing rather than armour. They were worn in a scabbard at the left hip, often matched with a dagger on the right hip for fighting in close. Swords were not just weapons but important decorative elements in masculine costume. They were symbols of honour and rank for their owners throughout Europe.

The classic rapier of the period 1570-1630 had a 'swept' hilt like this one. This was made up of interlinked bars and rings in front of and behind the guard sweeping in an elegant curve from the rear of the hilt to the knuckle guard.

Sword blades were articles of international trade, made in a few important centres and shipped all over Europe where they were fitted with hilts in the local fashion.

Rapiers were civilian weapons with long slender blades designed to pierce clothing rather than armour. They were worn in a scabbard at the left hip, often matched with a dagger on the right hip for fighting in close. Swords were not just weapons but important decorative elements in masculine costume. They were symbols of honour and rank for their owners throughout Europe.

The classic rapier of the period 1570-1630 had a 'swept' hilt like this one. This was made up of interlinked bars and rings in front of and behind the guard sweeping in an elegant curve from the rear of the hilt to the knuckle guard.

Sword blades were articles of international trade, made in a few important centres and shipped all over Europe where they were fitted with hilts in the local fashion.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Brief description | Rapier of ca. 1600, the French hilt encrusted with silver and inset with silver chains, the long slender blade signed by Fransisco Ruiz of Toledo, Spain. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Object history | Formerly in the collection of Mr Boldo de Bertodano of Malmesbury and sold at Sotheby's London, 7th july 1922. Subsequently in the collection of the dealer Andrade. The Museum bought the sword in 1953 from C. Falkiner for £125. |

| Historical context | Swords were not just weapons but important decorative elements in masculine costume. They were symbols of honour and rank for their owners throughout Europe. They remained an indispensible feature of outdoor dress of any person with pretensions to status until the late 18th century in Europe. The most common sword worn by gentlemen with their civilian dress from the middle of the 16th century onwards was the rapier. From 1560 it was applied almost exclusively to a fencing sword for civilian use. It was usual for rapiers to be accompanied by matching daggers. The rapier was a thrusting and slashing weapon with a slender light blade, while the dagger was more robust, used primarily for parrying and for thrusting in close. Rapier scabbards were suspended from a belt in a form of sling while the dagger was generally worn in a sheath on the left hip. In England rapiers were subject to sumptuary laws determining levels the of ostentation in which one might dress according to status. John Stow (ca. 1525- 1605) wrote of 'grave citizens' positioned by Royal decree at the gates of London who job it was 'to break the Rapier's poynts of all passengers that exceeded a yeard in length of their Rapier.' The classic rapier of the period 1570-1630 had a 'swept' hilt like this one. This was made up of interlinked bars and rings in front of and behind the guard sweeping in an elegant curve from the rear of the hilt to the knuckle guard. It afforded much more protection for the hand than the older straight quillons but was still not immune from the thrust of a thin rapier blade. Sword hilts became more and more elaborate after the introduction of firearms. Prior to that swords were used against armour primarily as cutting and thrusting weapons while the hand was protected by a gauntlet or by mail. Improvements to firearms made much armour redundant and so freedom of movement became more of a priority particularly as swords became more part of civilian dress. Civilians were unlikely to wear hand protection in the way a soldier would and a forward thrust would expose the hand to danger. Hilts became more elaborate as a result. Fencing as a training activity became increasingly codified and a standard part of male education. The most expensive hilts received the richest ornament that could be applied without impairing the sword's function. Sword blades were articles of international trade, made in a few important centres and shipped all over Europe where they were fitted with hilts in the local fashion. During the 16th and 17th centuries the sword blades of Toledo (such as on this example), Valencia and Milan were the most sought after but the largest centre of production was the German town of Solingen. The finest hilts were usually equipped with a Spanish blade but if not available a German blade (sometimes with a spurious Spanish inscription) was fitted instead. The most prosperous swordmakers in Toledo were concentrated in an area bordered by a road called Calle de Armas (Weapon Street) where there were also ironsmiths, crossbow makers, knife and axe makers. Guild regulations in Toledo were strict. Those seeking to practise as swordmakers had to pass strict tests of quality stipulated by the King. The King also protected the Spanish trade by issuing a decree in 1567: "... do not allow or permit to import any kind of sword in our kingdom from the exterior, and the ones made in Toledo wear the mark and signal of the master who made it and manufactured it, and the place where they are made, and whoever violates this they will be condemned as false." The maker of this blade, Francisco Ruiz, was from a family that for several generations produced high quality blades that were traded around Europe. |

| Summary | This rapier is composed of a hilt made in France, possibly by Claude Savigny of Tours, who was renowned for encrusting his hilts with silver chains, and a blade made in Toledo, by Francisco Ruiz, who was part of a famous family of bladesmiths. Rapiers were civilian weapons with long slender blades designed to pierce clothing rather than armour. They were worn in a scabbard at the left hip, often matched with a dagger on the right hip for fighting in close. Swords were not just weapons but important decorative elements in masculine costume. They were symbols of honour and rank for their owners throughout Europe. The classic rapier of the period 1570-1630 had a 'swept' hilt like this one. This was made up of interlinked bars and rings in front of and behind the guard sweeping in an elegant curve from the rear of the hilt to the knuckle guard. Sword blades were articles of international trade, made in a few important centres and shipped all over Europe where they were fitted with hilts in the local fashion. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.73-1953 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 23, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest