Perfume Flask

1671-1672 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This flask, one of a pair, was almost certainly part of a toilet service. Toilet services comprised items for grooming and breakfasting (such as combs, ointment pots, a mirror, candlesticks and bowls for broth), and the fashion for them originated in France. Flasks like this one are referred to in seventeenth-century inventories as 'ferrières', and held water scented with oranges for handwashing.

The marks on the flasks suggest the complexity of the French marking system and, perhaps, the subterfuges practised by goldsmiths. Both flasks bear the marks of different Paris goldsmiths. The very worn maker's mark on the base of one flask (V&A 806A & C-1892) is probably that of René Delacourt, a Paris goldsmith punished by the French authorities for fraud and pardoned in 1635. Jean Leroy, whose mark appears on the base of the other flask (V&A 806 & B-1892) was recorded in the London borough of Westminster in 1655 and was still resident in the city in the early 1670s. He was a contemporary of a third goldsmith, Geneviève Cabarin, whose mark appears on the sides of both flasks. Cabarin was the widow of the goldsmith Pierre Danet, and she took over his workshop after 1671. The location of these different goldsmiths' marks on the flasks appears to suggest that Cabarin's workshop made the cast side panels and soldered them to bases recycled from works made by the other two goldsmiths. Yet other scenarios are also possible. Cabarin and Leroy were contemporaries living in different cities. Did they know one another? Did Leroy, in fact, import silver made by Cabarin to London and add this to pieces made in his own workshop? This aside, the assay and tax marks struck on the base of both flasks are inconsistent. Both flasks bear a tax mark for 1672-74, which coincides with Cabarin's activity, but the assay letters on the flasks are for different, earlier, dates. If Cabarin did indeed assemble the flasks, this suggests some form of fraudulent activity on her part. Her workshop may have used substandard silver for the cast sides of the flasks and deliberately retained the worn assay marks on the recycled silver bases to make this appear legitimate.

The marks on the flasks suggest the complexity of the French marking system and, perhaps, the subterfuges practised by goldsmiths. Both flasks bear the marks of different Paris goldsmiths. The very worn maker's mark on the base of one flask (V&A 806A & C-1892) is probably that of René Delacourt, a Paris goldsmith punished by the French authorities for fraud and pardoned in 1635. Jean Leroy, whose mark appears on the base of the other flask (V&A 806 & B-1892) was recorded in the London borough of Westminster in 1655 and was still resident in the city in the early 1670s. He was a contemporary of a third goldsmith, Geneviève Cabarin, whose mark appears on the sides of both flasks. Cabarin was the widow of the goldsmith Pierre Danet, and she took over his workshop after 1671. The location of these different goldsmiths' marks on the flasks appears to suggest that Cabarin's workshop made the cast side panels and soldered them to bases recycled from works made by the other two goldsmiths. Yet other scenarios are also possible. Cabarin and Leroy were contemporaries living in different cities. Did they know one another? Did Leroy, in fact, import silver made by Cabarin to London and add this to pieces made in his own workshop? This aside, the assay and tax marks struck on the base of both flasks are inconsistent. Both flasks bear a tax mark for 1672-74, which coincides with Cabarin's activity, but the assay letters on the flasks are for different, earlier, dates. If Cabarin did indeed assemble the flasks, this suggests some form of fraudulent activity on her part. Her workshop may have used substandard silver for the cast sides of the flasks and deliberately retained the worn assay marks on the recycled silver bases to make this appear legitimate.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Silver, cast, chased, matted and gilded |

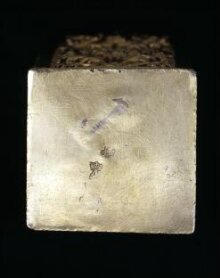

| Brief description | Perfume flask, with foliate decoration, silver-gilt, marks of Geneviève Cabarin, widow of Pierre Danet, and René Delacourt, Paris, around 1672. |

| Physical description | Of square section, with moulded base, and top corners rounded. Each side has a slightly recessed panel cast and chased in bold relief with a low base of auricular ornament from which rises a plant with spreading stems and curling foliage and a single large flower. It is closed by a single screw stopper with floral scrolls and topped by a trefoil handle. The chain that secured the lid to the loop soldered to the shoulder is missing. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Marks on the base:

The letter 'A' crowned by a closed (imperial) crown and surrounded by three fleurs-de-lys, the 'poinçon de charge' or tax mark for the tax official Vincent Fortier for the years 1672-74.

The letter 'A', crowned, the 'poinçon de jurande' or Paris assay mark for the year 1669-70 (according to Lightbown: 1978) or the year 1644-45 (Bimbenet-Privat: 2002).

A maker's mark, partly legible as a crown and, below, the letter 'R'. Tentatively identified by Lightbown (1978) as a maker's mark; identified by Bimbenet-Privat as the mark of René Delacourt (for identification see e-mail of 23/12/2013 in object file, Metalwork section, and for Delacourt see Bimbenet-Privat 2002: I, p. 302).

The gilding on the base has also been rubbed away in one part, and the trace of a zig-zag assay mark is faintly visible.

On the sides:

The letters 'PDN' over the letter 'V', between two pellets and below a bunch of grapes crowned by a fleur-de-lys, the mark of Genèvieve Cabarin, widow of Pierre Danet. This mark stamped once on one side of the flask and twice on the opposite side. Identified by Bimbenet-Privat (2002). |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | This flask and another like it, together with a two-handled cup and a broken candelabrum, were dug up by Edward Barrington Haynes, aged three, in July 1892 on Parliament Hill Fields between Hampstead and Highgate. A short report on the find featured in the 'Home and Foreign News' section of the Illustrated London News in August 1892, together with a photograph of the treasure. The flasks have French marks, the cup English ones, but despite this all the pieces probably came from a single toilet service. If so, the set may have been made up by another goldsmith, who obtained some of its pieces from the stock of his colleagues. A pair of Paris perfume flasks of 1670-71, with the mark of Pierre Prévost, with side panels of closely similar design, are now in the Metropolitan Museum (see Dennis: 1960, I, fig. 284J, p. 195). |

| Association | |

| Summary | This flask, one of a pair, was almost certainly part of a toilet service. Toilet services comprised items for grooming and breakfasting (such as combs, ointment pots, a mirror, candlesticks and bowls for broth), and the fashion for them originated in France. Flasks like this one are referred to in seventeenth-century inventories as 'ferrières', and held water scented with oranges for handwashing. The marks on the flasks suggest the complexity of the French marking system and, perhaps, the subterfuges practised by goldsmiths. Both flasks bear the marks of different Paris goldsmiths. The very worn maker's mark on the base of one flask (V&A 806A & C-1892) is probably that of René Delacourt, a Paris goldsmith punished by the French authorities for fraud and pardoned in 1635. Jean Leroy, whose mark appears on the base of the other flask (V&A 806 & B-1892) was recorded in the London borough of Westminster in 1655 and was still resident in the city in the early 1670s. He was a contemporary of a third goldsmith, Geneviève Cabarin, whose mark appears on the sides of both flasks. Cabarin was the widow of the goldsmith Pierre Danet, and she took over his workshop after 1671. The location of these different goldsmiths' marks on the flasks appears to suggest that Cabarin's workshop made the cast side panels and soldered them to bases recycled from works made by the other two goldsmiths. Yet other scenarios are also possible. Cabarin and Leroy were contemporaries living in different cities. Did they know one another? Did Leroy, in fact, import silver made by Cabarin to London and add this to pieces made in his own workshop? This aside, the assay and tax marks struck on the base of both flasks are inconsistent. Both flasks bear a tax mark for 1672-74, which coincides with Cabarin's activity, but the assay letters on the flasks are for different, earlier, dates. If Cabarin did indeed assemble the flasks, this suggests some form of fraudulent activity on her part. Her workshop may have used substandard silver for the cast sides of the flasks and deliberately retained the worn assay marks on the recycled silver bases to make this appear legitimate. |

| Associated objects | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 806A, C-1892 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 5, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest