Mirror Frame

ca. 1475-1500 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This idealised face once presided over a small, round mirror. Long-standing optical theories described how the eye received impressions from the objects it gazed upon. Since beauty was thought to be a sign of virtue, just looking at a beautiful face would inspire the viewer to virtue.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Cast in painted cartapesta (papier mâché) |

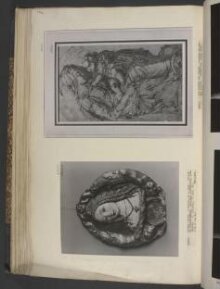

| Brief description | Mirror frame showing a female head, created in relief in painted cartapesta (papier mâché), workshop of Neroccio de' Landi, Italy (Siena), about 1475-1500 |

| Physical description | Mirror frame, created in relief in painted and gilded cartapesta (papier mâché). The frame comprises two putti hanging head-downwards with arms outstretched, holding a circular moulded border for the mirror (lost). Their torsoes emanate from floriated tails with interlacing stems. Above them, in an irregular space, is the head of a girl with elaborately dressed brown hair decorated with a jewel, wearing a gold dress with a white edge and a coral necklace and pendant. The flesh parts are painted naturalistically, and the head is set on a dull blue ground. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Historical context | The female figure in this frame closely resembles the Mary Magdalen in Neroccio's painting of a Madonna and Child in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. She has the same hairstyle and the same features - even the inclination of the head and the slant of the eyes are identical. There are also strong similarities with the Portrait of a Lady by Neroccio in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Both of these paintings date from last quarter of the 15th century and it seems likely that all three were produced after the same model and close in time. This theory was advanced by Gertrude Coor, who also suggested that the mirror frame was a squeeze (or cast) in cartapesta from a model by Neroccio, probably of clay. Coor also mentions that the iconography of Putti emerging from acanthus leaves was applied later by Neroccio on the Virgin’s chair in an altarpiece of 1496. Ellwood and Braun point out that children's heads with leaf mouldings were very a very popular border for picture frames, and Coor mentions Francesco di Giorgio's bronze candlesticks from Siena Cathedral, which also sport a design of leaves and putti. All this indicates that the this mirror frame presents fashionable and popular features, and it may have been one of a series. There has been some debate as to whether the figure is a portrait of a real person, or an idealised woman. The three similar depictions in very different contexts indicate that the latter is more likely. This is supported by Pope-Hennessy who argues against the portrait idea, firstly by pointing out the medium of the cartapesta , which he says, was an indication that several examples were produced, and secondly by connecting this frame with other mirror frame reliefs, one in cartapesta, three in maiolica and a fourth in wood which show idealised heads. Door Dia Peleen suggests that such mirrors were appropriate for a chamber, a bed chamber or camera, and indeed the iconography belongs to the female private sphere. Ajmar and Thornton argue that the belle donne on maiolica plates were gifts exchanged as part of betrothal or wedding rituals., partly because many of them have been found with piercing to allow wall-hanging. the link between the belle donne iconography and this mirror, may indicate that such mirrors were gifts from the groom to the bride., exchanged at the wedding or earlier in the courtship process., and then hung on the wall to commemorate the event. The image of idealised woman may be linked to the contemporary understanding of the face as the mirror of the soul. This theory had a tradition extending back to Greek civilisation where heroes were given an epithet meaning beauty. Renaissance viewers also connected outer signs of beauty with the inner beauty and goodness of the immortal soul. Such associations related to the growing interest in physiognomy, whereby traits such as courage or melancholy were believed to be reflected in facial features. In this context, women were expected to compare their own reflection with the idealised image above, and also, perhaps, to meditate on their own inner beauty, and to be encouraged to improve themselves, both inside and out, in emulation of the ideal woman depicted. Created from paper and cloth frayings, cartapesta was not in itself a valuable material, but this mirror frame was not necessarily destined for the low end of the market. As with other similar replicated sculptures in cheaper materails, the artistry of the painting would have added significant value, and it would have appealed to the noble and wealthy merchant classes. The painted and gilded surface on this example is substantially original, as revealed during cleaning in 1957 (Pope-Hennessy, p.270). Furthermore, objects created in cartapesta were not necessarily unusual. An inventory made in 1500 shows that they were a staple product of Neroccio's workshop. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This idealised face once presided over a small, round mirror. Long-standing optical theories described how the eye received impressions from the objects it gazed upon. Since beauty was thought to be a sign of virtue, just looking at a beautiful face would inspire the viewer to virtue. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 850-1884 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 20, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest