Textile Fragment

700-900 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

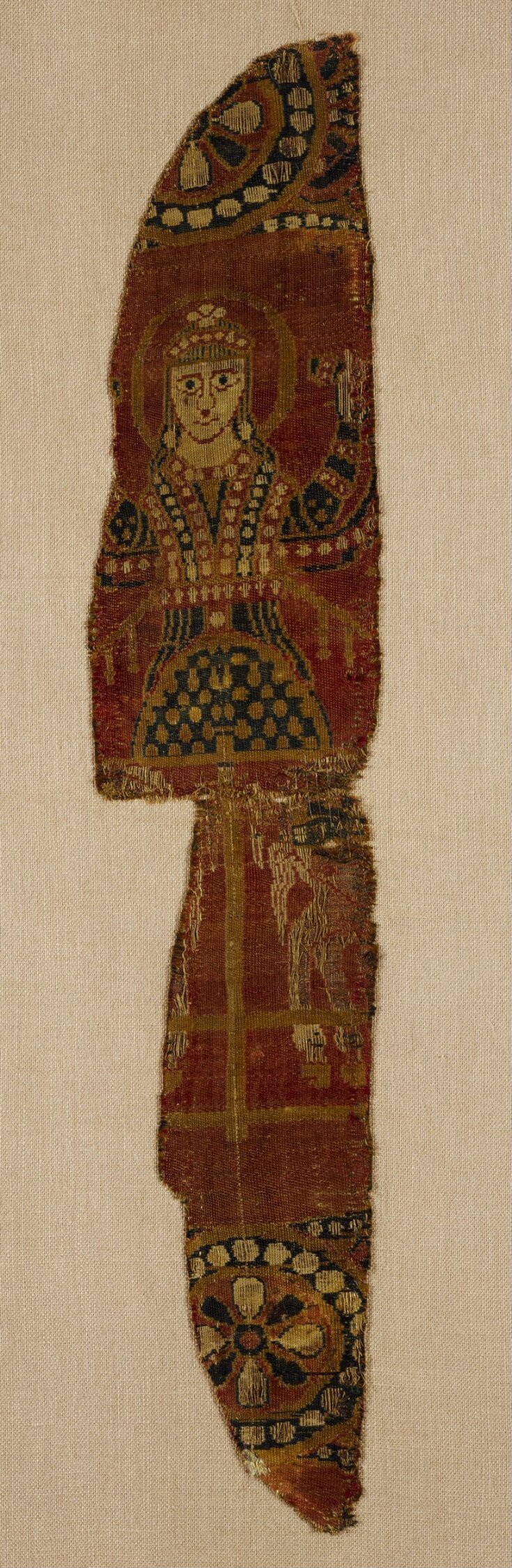

This textile fragment shows part of a scene of a triumphant Byzantine emperor in a quadriga (four horsed chariot). The halo denotes his imperial status. This is one of a group of 'charioteer' silks of the period, and by referring to more complete textiles of the type which survive, the original design can be reconstructed. One particularly notable piece is divided between the Cluny Museum in Paris and the Cathedral at Aachen, Germany (known in French as Aix la Chapelle), which is associated with the tomb of the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne.

The emperor with arms uplifted in triumph would originally have been seated or standing in a chariot with two rearing horses to either side of him, (part of one can be seen below him to the right). The bars forming part of the construction of the chariot can be seen running down the centre from beneath the emperor. The scene was framed within a roundel with rosettes at the junctions (one can be seen at the top and another at the bottom of the fragment) and repeated over the whole textile. The pattern would have been grand in scale, with a diameter of about 41 cm, and suggests that the textile may have been the product of an imperial workshop in Constantinople.

The emperor with arms uplifted in triumph would originally have been seated or standing in a chariot with two rearing horses to either side of him, (part of one can be seen below him to the right). The bars forming part of the construction of the chariot can be seen running down the centre from beneath the emperor. The scene was framed within a roundel with rosettes at the junctions (one can be seen at the top and another at the bottom of the fragment) and repeated over the whole textile. The pattern would have been grand in scale, with a diameter of about 41 cm, and suggests that the textile may have been the product of an imperial workshop in Constantinople.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Silk cloth with compound weave |

| Brief description | Woven silk with part of the scene of an emperor in a chariot;700-899; Turkey |

| Physical description | Two fragments of purple red silk, joined together: compound twill weave in green, white and yellow (1/2 weft faced twill, paired main warps) depicting a triumphant Byzantine Emperor in a quadriga, or four-horsed chariot, surrounded by a circle. Visible is part of the Emperor who wears a diadem with a cross and a halo and raises his arms in a victorious gesture, parts of the horses, the reins and the chariot. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Object history | Bought from Monsieur Stanislas Baron, rue Grange-Batelière 28, Paris for £30 (there were two pieces at this stage, both accessioned as this number). In the Accession Register, the precise wording with regard to this piece is 'Said to have at one time enveloped the relics of a bishop of Verdun in a chasse', so there is some doubt around the provenance. Historical significance: Significant as an example of a piece of Byzantine silk with a relatively complex figurative pattern, with an apparently firm provenance in a European religious centre. |

| Historical context | Silk production 'Byzantine' silks were made in the east of the Roman Empire, the capital being Constantinople, long before the Latin West developed its own silk-weaving workshops. Raw silk was originally imported from China via Persia, but from the fifth century there are records of sericulture being practised in Byzantine Syria. Silk weaving was already established there by the 4th century and continued even after the fall in 1204 AD. This piece belongs to second phase of pre-thirteenth century weaving, a period after the Islamic conquests of Byzantine territory in the seventh century, including Egypt and Syria, when imperial production was centralised in Constantinople, and private workshops began to take root there also. In the city's guild regulations (The Book of the Prefect ) in the tenth century, five private silk guilds were represented. Only the imperial workshops were, however, allowed to make up certain shades of imperial purple, and certain types of tailored silk garments reserved for the imperial house. Use and trade In the tenth century, The Book of Ceremonies described the place of silk vestments and furnishings in the life of the court: imperial purple, golden, green, blue and red silks; plain silks and silks decorated with eagles, griffins, bulls and hornets or foliate motifs. This magnificence reached foreign nations via diplomatic channels and the sending of silks as gifts to foreign courts.The demand for these silks was great as the Latin West did not make silks of its own, and the Italians, the Bulgars and the Russians defended with military force the Byantine territories in exchange for silk-trade concessions and silken gifts. The Venetians and the German emperors had a particularly close relationship right through the eighth to twelfth centuries. Not surprisingly, most of the silks that survive from this period are to be found in ecclesiastical treasuries. Bibl: Anna Muthesius, 'Byzantine Silks' in 5000 Years of Textiles. London: British Museum Publications, 1995, pp. 75-80. The pattern Although the complete pattern on this silk is not available, it may be reconstructed by reference to other comparable silks. The whole image depicts either a chariot race or the state image of the Emperor in his chariot; it was probably repeated within adjacent circles, with rosettes. The rosettes can be seen at the top and bottom of the fragment, at the junction of the roundels; they seem to have a diameter of approx. 41 cm. The bands were filled with a guilloche pattern. Combinations of bright reds, blues, greens and yellows were prevalent in the eighth to ninth centuries in paritcular. Depiction of clothing The figure is dressed as Byzantine ruler in a pearled costume. The image of the Emperor in his chariot appears on Byzantine coins from the time Constantine, and the racing chariot is depicted on Roman and Byzantine ivories. Such a particular image, though popular in other media, appears only a few extant textiles and must presumably have been specially commissioned. The best-known image of the Byzantine emperor is in the mosaics at Ravenna. Similar pieces One notable piece, which is divided between the Cluny Museum in Paris and the Cathedral at Aachen is associated with the tomb of Charlemagne, who died in 814. Illustrations of similar subjects in the Freiburger Münsterblätter, 2 Jahrgang, 1. Heft, p. 12 and in L'Epopée Byzantine, Vol. II, p. 36 (Collection of M. F. Liénard). |

| Production | Found in a shrine at Verdun in France |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This textile fragment shows part of a scene of a triumphant Byzantine emperor in a quadriga (four horsed chariot). The halo denotes his imperial status. This is one of a group of 'charioteer' silks of the period, and by referring to more complete textiles of the type which survive, the original design can be reconstructed. One particularly notable piece is divided between the Cluny Museum in Paris and the Cathedral at Aachen, Germany (known in French as Aix la Chapelle), which is associated with the tomb of the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne. The emperor with arms uplifted in triumph would originally have been seated or standing in a chariot with two rearing horses to either side of him, (part of one can be seen below him to the right). The bars forming part of the construction of the chariot can be seen running down the centre from beneath the emperor. The scene was framed within a roundel with rosettes at the junctions (one can be seen at the top and another at the bottom of the fragment) and repeated over the whole textile. The pattern would have been grand in scale, with a diameter of about 41 cm, and suggests that the textile may have been the product of an imperial workshop in Constantinople. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 762-1893 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 17, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest