Panel

1296 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

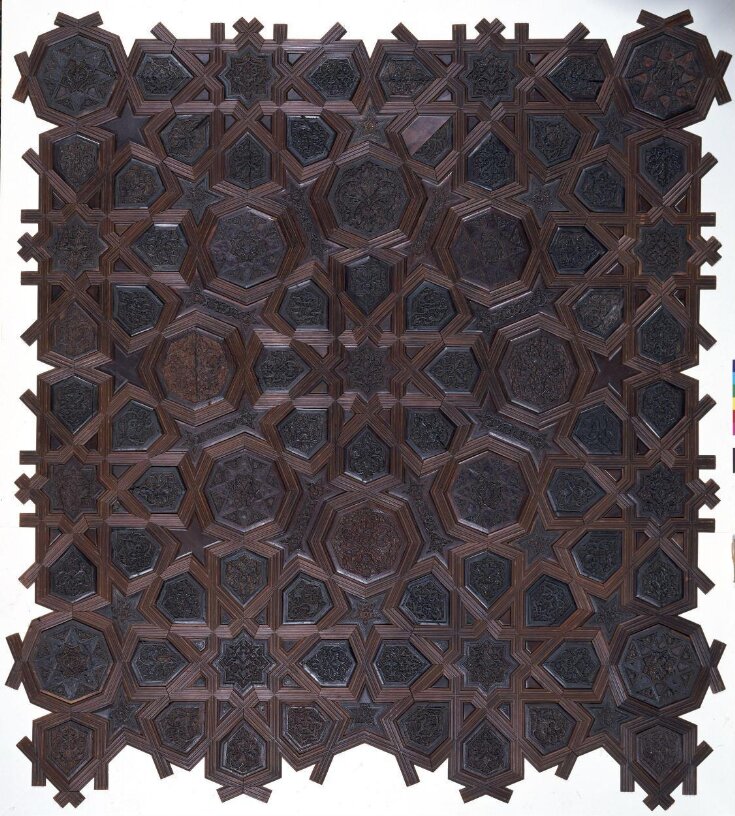

This panel with carved geometric decoration forms most of one flank of a minbar or mosque pulpit. It was presented to the 9th-century mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo by the Mamluk Sultan Lajin (ruled 1296-1299) as one element in an extensive restoration. In 1294, when he was a Mamluk officer, the Sultan hid from his enemies in the ruined mosque. He vowed to restore it should his circumstances improve. He kept his vow.

Most Islamic ornament was governed by principles of geometry. This panel reflects the elegant use of straight lines and regular patterns, seen here in a religious context.

Most Islamic ornament was governed by principles of geometry. This panel reflects the elegant use of straight lines and regular patterns, seen here in a religious context.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Carved wood |

| Brief description | Geometric panels, carved wood, forming an interlocking radial pattern, from the side panel of a minbar made for Mamluk Sultan Lajin, Cairo, Egypt, 1296, rearranged in this formation c.1869 |

| Physical description | Part of the side of a minbar composed of plaques carved from different woods and set into a modern geometric framework. The minbar from which these plaques originally came was presented to the 9th-century mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo by the Mamluk Sultan Lajin (1296-99), as one element in an extensive restoration programme. The plaques are delicately carved with 'arabesque' motifs, in two levels of relief. This style was characteristic of early Mamluk carving, and no two designs are identical. This minbar is also notable for containing no ivory plaques: ivory inlay became popular on later Mamluk furniture (for example, on Sultan Qa'itbay's minbar, Museum no.1050-1869), but here the colour contrast is provided by the use of different woods. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | Purchased in Paris as part of "Dr Meymar's Collection", a group of historic objects sent to France by the Egyptian government, for display at the international exhibition of 1867. "Dr Meymar" was Husayn Fahmi (c.1827-1891), also called Husayn Pasha al-Mi`mar or al-Mi`mari (transliterated as "Meymar", meaning architect), a senior official in the Egyptian administration. He was (in 1864) the chief architect of the Majlis al-Tanzim wa'l-Urnatu, a committee in charge of public works in Cairo, and later (1882-5) a member of the Comite de conservation des monuments de l'Art arabe, which oversaw Cairo's historic heritage. Throughout his career, he was responsible for salvage and removal of historic architectural fittings, and for the construction of modern monuments and streets in the Egyptian capital. Reporting on the 1867 Paris exhibition, Adalbert de Beaumont noted that "Dr Meymarie" had recovered many decorative woodwork fragments from the mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, damaged during renovations to the mihrab area. This comment indicates the means by which these and other panels (in the V&A, as well as in other museum collections) were removed from the Lajin minbar during the second half of the nineteenth century. The following is extracted from Stanley Lane-Poole, Art of the Saracens in Egypt (1886), pp.111-117: “The removal [of this minbar from the mosque of Ibn Tulun] must have been effected in comparatively recent times, for when Mr James Wild, the present Curator of Sir John Soane’s Museum, was in Cairo, about 1845, the older pulpit was still standing; and he made a drawing of the geometrical arrangement of the panels, which is still preserved in his sketch-books, and which was turned to advantage some years ago, when the fragments of the pulpit-sides were acquired by the South Kensington Museum from M. Meymar. This sketch shows that the side included one large circular geometric arrangement (comprising 8 large octagonal panels, carved alternately with stars and arabesques round a central star), and 4 half-systems of the same plan, 2 of which were placed so that their diameters coincided with the edge of the balustrade or border of the pulpit, while the other two touched the back. The balustrade was of open lattice work, something like the narrow open panels in the Kâït Bey pulpit engraved in fig.34, and the length of the base and back of the triangular portion of the side, occupied by the carved panels, was 15 feet 9 inches. The doors were filled with carved geometrical panels, with the usual arrangement of 2 horizontal panels, filled with Arabic inscriptions, one above and one below each door, and a longer inscription on the lintel. The pulpit did not arrive in England in its original shape, but consisted merely of a collection of loose panels, which Mr Wild, with the help of his sketch, arranged in a square, which now hangs on the walls of the Museum (no.1051); with the exception of a few pieces which remained over, and some of the horizontal panels, 2 of which contain the name of Sultan Lajin and the date of the erection of the pulpit, AH 696, while others are filled with scrollwork. Two of these are engraved in figs 39 and 40; one has an arabesque scroll, and the other the inscription ‘Al-Malik al-Mansur Husam al-Dunya wa al-Din Lajin’, ‘The victorious king, sword-blade of the State and Church, Lajin’. When the Museum acquired the magnificent collection of M. de St Maurice, in 1884, I was able to identify the fine panels [also from the Lajin minbar] which the late owner had fitted into the framework of a modern and ill-proportioned door as portions of the same pulpit, and some of these are engraved in figs 37 and 38. [...] The panels of Lajin’s pulpit show Cairene carving in its boldest and finest style. Later arabesques may be more delicate and graceful, but no carvers in Egypt excelled those who made this pulpit, in freedom of design and skill of execution. As is usual in the best Saracenic work, no two designs of this pulpit are absolutely identical: some fresh turn, some ingenious variation in the lines of the arabesque, show the independence of the artist from servile copying. The panels are enclosed by two thin lines of light-coloured wood inlaid in the darker wood of the panel, but the borders are not carved in the manner usual in later work, nor is there any ivory inlay.” |

| Historical context | The plaques are delicately carved in two levels of relief, a characteristic of early Mamluk carving, and no two designs are identical. This panel is also notable for containing no ivory plaques: ivory inlay became popular on later Mamluk furniture, but here the colour contrast is provided by the use of different woods. |

| Production | Made for the restoration of the mosque of Ibn Tulun by Sultan Lajin (r. 1297-9). Dated 1296. |

| Subject depicted | |

| Associations | |

| Summary | This panel with carved geometric decoration forms most of one flank of a minbar or mosque pulpit. It was presented to the 9th-century mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo by the Mamluk Sultan Lajin (ruled 1296-1299) as one element in an extensive restoration. In 1294, when he was a Mamluk officer, the Sultan hid from his enemies in the ruined mosque. He vowed to restore it should his circumstances improve. He kept his vow. Most Islamic ornament was governed by principles of geometry. This panel reflects the elegant use of straight lines and regular patterns, seen here in a religious context. |

| Associated objects |

|

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 1051-1869 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 1, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest