The Stein Collection

Textile

9th century to 10th century (made)

9th century to 10th century (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

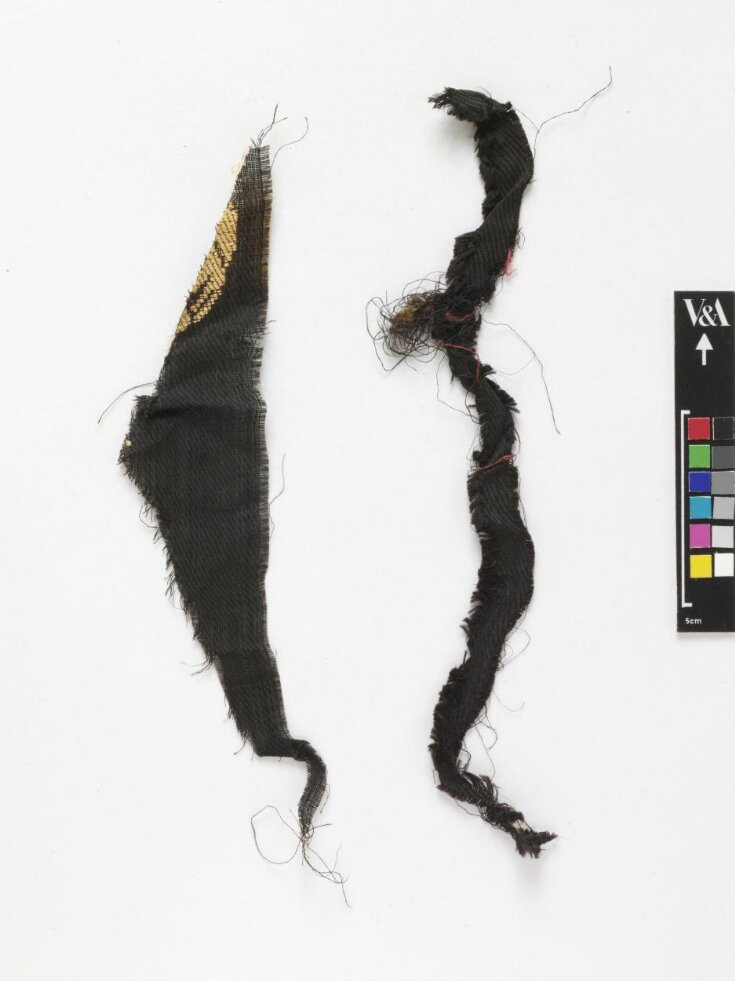

These two textile pieces are of black silk with the remains of coloured patterns evident. It is unclear what they would have been used for although they are likely to have had a decorative purpose.

This textile was brought back from Central Asia by the explorer and archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943). It was recovered from Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes. This shrine site is one of China’s great Buddhist pilgrimage complexes and is situated near the oasis town of Dunhuang. The shrines were carved out of the gravel conglomerate naturally occurring in the region. The insides of each cave-shrine were painted with coloured murals, some of which survive to this day. By the Tang dynasty (618-906 AD), from which this textile dates, there were a thousand caves decorated with religious scenes.

Most of the textiles from this site would have been used as banners or wrappers for religious texts. The site is also part of an area of Central Asia we now call the Silk Road. This term was first used by the German scholar Ferdinand von Ricthofen (1833-1905) and it refers to a series of overland trade routes that crossed Asia from China to Europe. The most notable item traded was silk. Camels and horses were used as pack animals and merchants passed the goods from oasis to oasis. The Silk Road was also important for the exchange of ideas. While silk textiles travelled west from China, Buddhism entered China from India in this way.

This textile was brought back from Central Asia by the explorer and archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943). It was recovered from Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes. This shrine site is one of China’s great Buddhist pilgrimage complexes and is situated near the oasis town of Dunhuang. The shrines were carved out of the gravel conglomerate naturally occurring in the region. The insides of each cave-shrine were painted with coloured murals, some of which survive to this day. By the Tang dynasty (618-906 AD), from which this textile dates, there were a thousand caves decorated with religious scenes.

Most of the textiles from this site would have been used as banners or wrappers for religious texts. The site is also part of an area of Central Asia we now call the Silk Road. This term was first used by the German scholar Ferdinand von Ricthofen (1833-1905) and it refers to a series of overland trade routes that crossed Asia from China to Europe. The most notable item traded was silk. Camels and horses were used as pack animals and merchants passed the goods from oasis to oasis. The Silk Road was also important for the exchange of ideas. While silk textiles travelled west from China, Buddhism entered China from India in this way.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Stein Collection (named collection) |

| Materials and techniques | Pattern-woven silk |

| Brief description | Two silk fragments with roundel, brocaded on twill (zhuang hua ling), found in Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, 800-1000 |

| Physical description | Two pieces; one triangular piece and one strip of polychrome patterned weave both with black silk ground. Triangular piece shows incomplete roundel design in orange silk. The strip piece has a number of threads of different colours entangled. Weave structures: Warp: silk, S twisted, single, black, 65 warps/cm; Main weft: silk, black, 22 wefts/cm; Supplementary weft: wilk, yellow, 22 passes/cm. Pass 1 main and 1 supplementary weft. Weave structure: 5/1S twill for foundation and 1/5S twill for brocade |

| Dimensions |

|

| Styles | |

| Credit line | Stein Textile Loan Collection. On loan from the Government of India and the Archaeological Survey of India. Copyright: Government of India |

| Object history | Attached to one fragment is a circular sticky label showing Stein number possibly in Stein's handwriting or that of his assistant Miss F.M.G. Lorimer. |

| Historical context | Dunhuang is at the eastern end of the southern Silk Road, in present-day Gansu Province. It lies between the western reaches of China and the Tarim Basin. When China began to expand into Central Asia during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), Dunhuang served as a base for military operations and trade. In the succeeding centuries, Buddhist shrines were established southeast of Dunhuang in a series of man-made caves called Qianfodong, "Caves of the Thousand Buddhas" (today also known as the Mogao Grottoes). Here spectacular cave temples were cut out of the cliffs, beginning in the fourth century AD. Over a period of several centuries, communities of Buddhist monks filled the caves with splendid sculpture and wall paintings. These included colossal Buddha statues, painted clay sculptures of deities, elaborate murals of Buddhist legends, and thousands of tiny painted Buddha images; all of which gave the site its name, Qianfodong. Buddhist cave temples had first been established in at Bamiyan (Afghanistan) and Gandhara (formerly in India, now Pakistan). At Qianfodong, Stein found paintings of graceful figures in the Gandharan style among landscapes and buildings that were distinctly Chinese; a fusion of Indian and Chinese art, which he had noted elsewhere along the Silk Road. In 1900, a Daoist monk named Wang Yuanlu discovered a secret cave at Qianfodung, which contained thousands of documents and paintings. Stein purchased a significant amount of this material from Wang during his visit to the Dunhuang in 1907. Among the many religious works were Buddhist, Jewish, Nestorian, Daoist and Confucian texts; all of which dated from approximately 400 to 1000 A.D. Numerous languages were represented as well, including Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan and Hebrew. Stein also acquired many textile pieces. Most of these were silk, for Dunhuang lay on the main trade route between silk-growing regions of China and Central Asia. Elaborate embroideries depicted Buddhist legends and processions of donors. Patterned silks included Chinese and Sassanian (Persian) designs. From China came floral and geometric patterns, combined with figures of animals and birds. Sassanian motifs included pairs of confronted ducks, lions, and other beasts, combined with medallions and quatrefoils. Stein also found undecorated silks used as processional banners and valances for decorating bases of statues. The cave was sealed soon after 1000 A.D., apparently to protect the contents from invading armies. The V&A holds, on loan, a large number of textiles from Dunhuang, including plain and pattern woven silks in many colours, painted Buddhist banners and canopies, and wrappers for Buddhist texts. |

| Production | Found in Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes (Caves of the Thousand Buddhas). |

| Association | |

| Summary | These two textile pieces are of black silk with the remains of coloured patterns evident. It is unclear what they would have been used for although they are likely to have had a decorative purpose. This textile was brought back from Central Asia by the explorer and archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943). It was recovered from Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes. This shrine site is one of China’s great Buddhist pilgrimage complexes and is situated near the oasis town of Dunhuang. The shrines were carved out of the gravel conglomerate naturally occurring in the region. The insides of each cave-shrine were painted with coloured murals, some of which survive to this day. By the Tang dynasty (618-906 AD), from which this textile dates, there were a thousand caves decorated with religious scenes. Most of the textiles from this site would have been used as banners or wrappers for religious texts. The site is also part of an area of Central Asia we now call the Silk Road. This term was first used by the German scholar Ferdinand von Ricthofen (1833-1905) and it refers to a series of overland trade routes that crossed Asia from China to Europe. The most notable item traded was silk. Camels and horses were used as pack animals and merchants passed the goods from oasis to oasis. The Silk Road was also important for the exchange of ideas. While silk textiles travelled west from China, Buddhism entered China from India in this way. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Other number | Ch.00364 - Stein number |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | LOAN:STEIN.419 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 4, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest