Door and Doorway

ca. 1500-1530 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

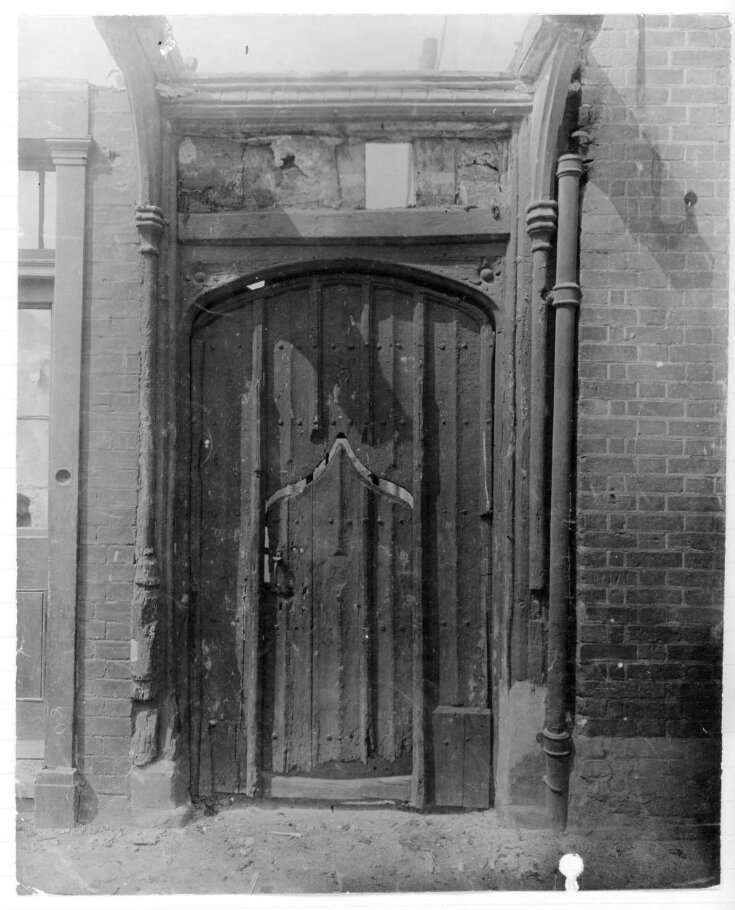

The strength of this massive door lies in its construction. It has thick, broad planks that are strengthened by carved uprights and studded with stout iron nails. Decoration is minimal, just foliage in the corners of the doorpost. The door came from a house in Ipswich in Suffolk and opened onto the street. The inner or wicket door was more convenient for regular access.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 4 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Oak |

| Brief description | Door and doorway, oak with carved acanthus leaves, England, ca. 1500-1530 |

| Physical description | Doorway and door set within a larger structural framework with two brackets above (originally supporting a jetty), and three blocks jointed between the lintel and above a beam with dentil front edge. The jambs are moulded and have superimposed small circular columns with moulded capitals and bases and are surmounted by carved brackets. The doorway has a depressed arch with narrow spandrels filled with conventional foliage. The door appears to be constructed with butted vertical planks nailed onto a sub-support. On its front it is reinforced by vertical timber moulded braces. Early Museum descriptions say that it is carved with a simple linenfold pattern. Within the main door a smaller door, or wicket, with an ogee-shaped head has been cut, and supplied with a modern metal latch. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Given by Sir George Donaldson |

| Object history | From a house formerly in Key Street, Ipswich (Suffolk). Given by Sir George Donaldson, Thornwood Lodge, Campden Hill, London and later of 2, Eastern Terrace Brighton (who was in the process of converting a large house in Hove into a museum in 1912, and interested in obtaining a wood copy of the Museum carved oak ceiling, then in room 7 but otherwise unidentified, and a plaster copy of the Sizergh Castle room reproduction plaster ceiling), who purchased it on May 24th 1913 from Frederick Tibbenham of Ipswich (apparently a firm) for £50 incl. delivery to the Museum. Donaldson wrote to Sir Cecil Smith on May 28th 1913 "A house in Key Street Ipswich is coming down in a few weeks and I have bought the Tudor doorway. Herein [?] a sketch [on RF, copy in FWK file] and the vendor has promised to send a photograph shortly [on FWK file]....PS Shall I tell the owners to send the drawing direct to the Museum?" It is clear that when it was given to the Museum it was stripped of paintwork: Eric Maclagan wrote (about the problem of finding space for the doorway) on a Museum memo 24/6/1913 "With the paint off, I daresay this door of Sir George Donaldson's would be attractive in its way, but the period is rather well represented" The pencil drawing of the doorway (apparently made before removal) shows it within a timber framed building, set on a brick course about 90cm off the ground. However it does not show the deterioration along the bottom of the wicket door, nor the iron latch and handle visible in early Museum photographs. A drawing dated Sept 1st 1888 by J.S.Corder in his ‘Old Ipswich’ (1898), titled ‘Quay Street, Ipswich. ‘ [annotated] Taken down 1913-14’ shows the V&A doorway in situ, opening inwards on a paved area, the lighting of which may suggest a courtyard. An inset drawing captioned ‘The House’ shows the door (and another, smaller door) to the right of a twin-gabled, three storey house with the second floor jettied, and a brick chimney, with adjoining properties either side (ie not a corner property). It is possible that the VA door came from the Bull Inn on Key Street. Ogilby’s 1672 map of Ipswich shows Key Street running E-W behind the quay, on which the Customs house and crane are easily identifiable, and a large courtyard property facing the quay, just behind (off to one side) the Customs House, which seems to represent the Bull Inn (personal communication from David Jones, curator, Ipswich Museum). A detail of John Cleveley the Elder’s View of Ipswich (Wolsey Art Gallery), c.1754 shows the quay, crane, Customs house, and the Bull Inn. It shows the latter as a twin-gabled, three-storey building, the fenestration of which however differs from the Corder view made 140 years later. Two factors should be taken into account before attempting to match the Corder and Cleveley properties: Cleveley’s townscape is a very small part of the whole picture and may well show typical town houses without attempting architectural accuracy at the level of individual properties; besides the Bull Inn in Key street, which was known for the residences of wealthy merchants, other properties would have had similar doorways to the Museum’s example. Without further evidence, it is not possible to say that the VA doorway came from the Bull Inn. Key street was an important area of Ipswich, whose proximity to the quay led to wealthy merchants owning substantial properties there, which would have provided warehousing for goods, and the means to accommodate visitors and deliveries. There was a considerable trade in antique woodwork in Ipswich before 1913 (personal communication from David Jones, curator, Ipswich Museum). Tibbenhams was a firm of furniture restorers who specialised in making "Jacobethan" furniture and house restoration using genuine and made up panelling, along with at least two others frederick Fish and Sons, Titchmarsh and Goodwin. In theory it would be possible but time-consuming to identify the owner as Entries Upon the Rolls and the Dogget Rolls for Ipswich survive giving details of all property transactions in the parish of xx the south head bordering on the highway the north on tenement in the possession of " " all that principal messuage now x late ys" . These have been transcribed in mss. form. It was clearly a major property and thus the owner is likely to have had a career (also documented) on the Town Council. |

| Historical context | See - Salzman, Building in England down to 1540 (Oxford 1952) Medieval building was emphatically in oak. Scarcity of good quality was remarked on by 13c and by mid 15c the price of timber had risen enormously: for timbers, laths (5' x 1"[or 2"] x ½" or ) and boards (of various names, planks the thickest), averaging 10' x 1 ½" x 1 ½". From late 13c imports of timber to England came from Baltic and north sea ports of Hanseatic League - via all the East coast ports from Newcastle to Dover. Such imported timber was used all over England, and is referred to in documents as 'bord de Alemain', (1275), or more usually 'Estland' or 'Estreche', reckoned by the long hundred, ie 120, a standard length of 10'. Common sorts of timber were Dutch wainscot (probably derived from the word used originally for wains or wagons) or German Righolts from Riga, being larger and more expensive. Imported timber was better seasoned than the local stuff, and sometimes therefore specified for doors and screens. Chapter XVII Doors, Shutters, Panelling, Screens pp.253-261 Doors, provided by the carpenter were obviously an essential element of medieval buildings. In a stone-built edifice, the door frames were usually of stone; in a timber frame they were usually of wood but constructionally similar. Doors were usually supported by braces (square sectioned bars) known as ledges (often written as ‘legges’) crossing at right angles or diagonally. Large gates or doors were often provided with a smaller ‘wicket’ in, or beside it, which might be provided with its own lock. Margaret Wood, The English Medieval House (London 1965) cites surviving medieval doors at Athelhampton Hall, Dorset (1495-1500) and Yanwath Hall, Westmoreland (late 15th century). |

| Production | Ipswich, Suffolk |

| Summary | The strength of this massive door lies in its construction. It has thick, broad planks that are strengthened by carved uprights and studded with stout iron nails. Decoration is minimal, just foliage in the corners of the doorpost. The door came from a house in Ipswich in Suffolk and opened onto the street. The inner or wicket door was more convenient for regular access. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.25:1, 2-1913 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | October 6, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest