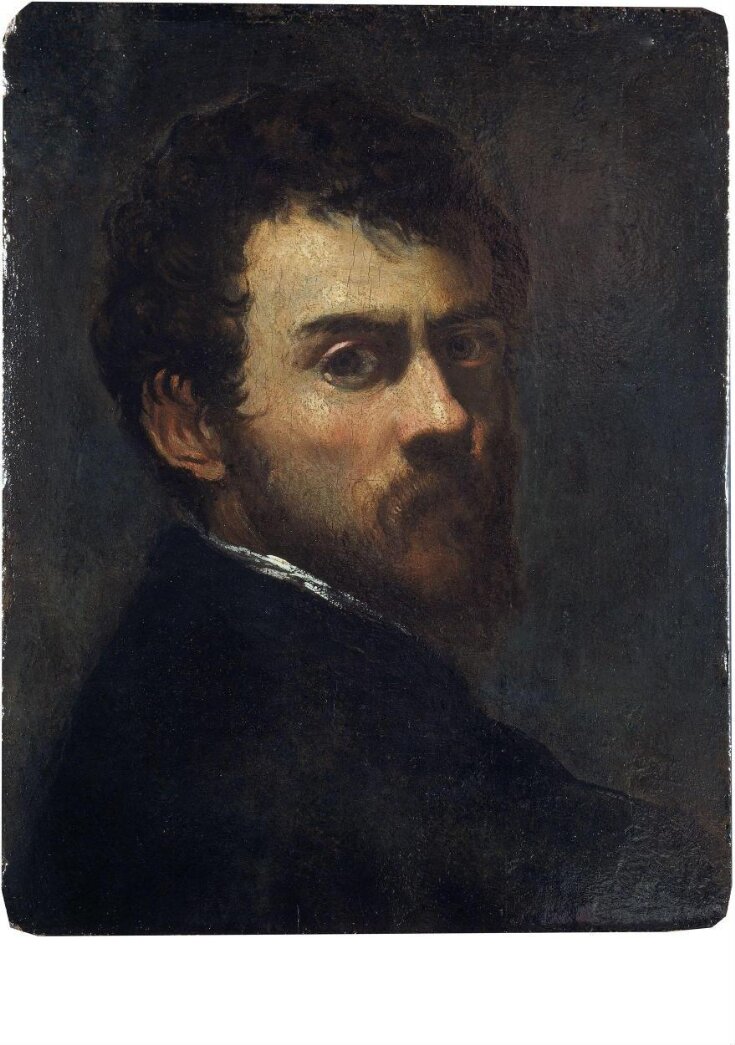

Self-Portrait as a Young Man

Oil Painting

ca. 1548 (painted)

ca. 1548 (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This early and forceful self-portrait, by one of the greatest Venetian painters, was done with the aid of a mirror. Portraits of artists became popular with collectors during the Renaissance. Ionides bought this work in the belief that it was by Titian.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Titles |

|

| Materials and techniques | oil on pine panel |

| Brief description | Portrait of a man's head and shoulders, head turned to the right, as if looking in a mirror. Oil on pine panel. Self-portrait by Tintoretto, about 1548. |

| Physical description | A bust-length painted portrait of a young man standing perpendicular to the picture plane, head turned over his shoulder to the right |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Bequeathed by Constantine Alexander Ionides |

| Object history | Provenance: Perhaps in the collections of Alessandro Vittoria (1525-1608) and/or Nicolo Crasso, Venice; Christie's, 20th Jan. 1883, lot 52 as 'Titian, Head of a Man; and a portrait'; bought by Constantine Alexander Ionides for £2.2s.0d.; his inventory (private collection) 20 January 1883 at a valuation of £80; bequeathed by C.A. Ionides in 1900. It was published by Detlev, Baron von Hadeln, not only as an original work by Tintoretto, but as an early self-portrait, perhaps the one that belonged to the sculptor Alessandro Vittoria. [Burlington Magazine xliv 1924 p.93.] Historical significance: Jacopo Tintoretto (1519-1594) was the most prolific painter working in Venice in the later 16th century. His father was a cloth-dyer, a common and respectable occupation in Renaissance Venice and Jacopo’s adopted nickname ‘tintoretto’ meaning ‘the little dyer’ advertised his artisan background. We know little of his artistic training, although early sources report that he was expelled from Titian’s workshop after a short period, as a result either of the jealousy or incomprehension of his master. He worked in a quick, abbreviated style and his intentional the lack of conventional finish was seen by some as careless and caused controversy among his contemporaries. This self-portrait was presumably painted with the aid of a mirror, and is customarily dated around 1546/8 when the artist was 30 years old. There is an autograph, near identical composition of similar dimensions (canvas, 45.7 x 38.1cm), with a Venetian provenance, in the Philadelphia Museum of Art which also appears to have been painted from life. While Tintoretto apparently painted several other self-portraits, the only other identified work is the much later Louvre half-length portrait (ca. 1588, canvas, 63 x 52cm) in which he is represented frontally. According to the 1608 posthumous inventory of Alessandro Vittoria, the collector posessed a small Tintoretto self-portrait as a young man which may refer to CAI 103 or the Philadelphia portrait. The existence of a Flemish copy suggests that one of these versions may be identified with that recorded in Rubens’ collection by 1640. While many artists depict themselves with the tools of their trade, or wearing the finery of gentleman, Tintoretto represents himself with an intense penetrating gaze, perhaps suggestive of peering into a mirror, and omits his hands, the very means by which the work was created. |

| Historical context | In order to creat self-portraits in this period, artists used circular convex mirrors as represented in Franco-Flemish illuminated manuscripts of the early fifteenth century. Artists made drawings of themselves as a routine exercise, and their portraits sometimes appear in group compositions, especially in fifteenth century Florence. The two principal centres of mirror-manufacture in Europe were Nuremberg and Venice, and Albrecht Dürer, who lived in the former city and frequented the latter, was arguably the first artist to excel in self-portraiture. Flat mirrors began to become available by the early sixteenth century, but the older type remained more usual. Artists customarily adjusted likenesses to compensate for the distortions which occurred at the periphery of their convex field, while Parmigianino spectacularly exploited this characteristic in his famous self-portrait of 1524, now in Vienna. Renaissance self-portraiture appears symptomatic of the growing aspirations of artists to emphasise the intellectual content of their activity, and enhance their social status. (Joanna Woods-Marsden, Renaissance Self-Portraiture, New Haven & London 1998) Sketching in oils was increasingly practiced from the early sixteenth century, especially by Northern Italian artists. Tintoretto made few preparatory drawings. According to his 17th century biographer Carlo Ridolfi, Tintoretto painted a self-portrait and a likeness of his brother, presumably for speculative sale, as they were displayed in the Merceria, the principal shopping street in Venice. One of the earliest known collections of artists’ portraits, assembled by the Venetian sculptor Alessandro Vittoria (1525?-1608), included a likeness of Tintoretto, Titian, Veronese, Palma Giovane and the celebrated self-portrait of Parmigianino. In 1664, the Florentine Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici (1617-75) inaugurated the major collection of self-portraits, continued by his successors, now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. |

| Production | Acquired by Ionides in 1883 as Titian 'Head of a Man; and a portrait' |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | This early and forceful self-portrait, by one of the greatest Venetian painters, was done with the aid of a mirror. Portraits of artists became popular with collectors during the Renaissance. Ionides bought this work in the belief that it was by Titian. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | CAI.103 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | May 13, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest