Scissors

1760-1780 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

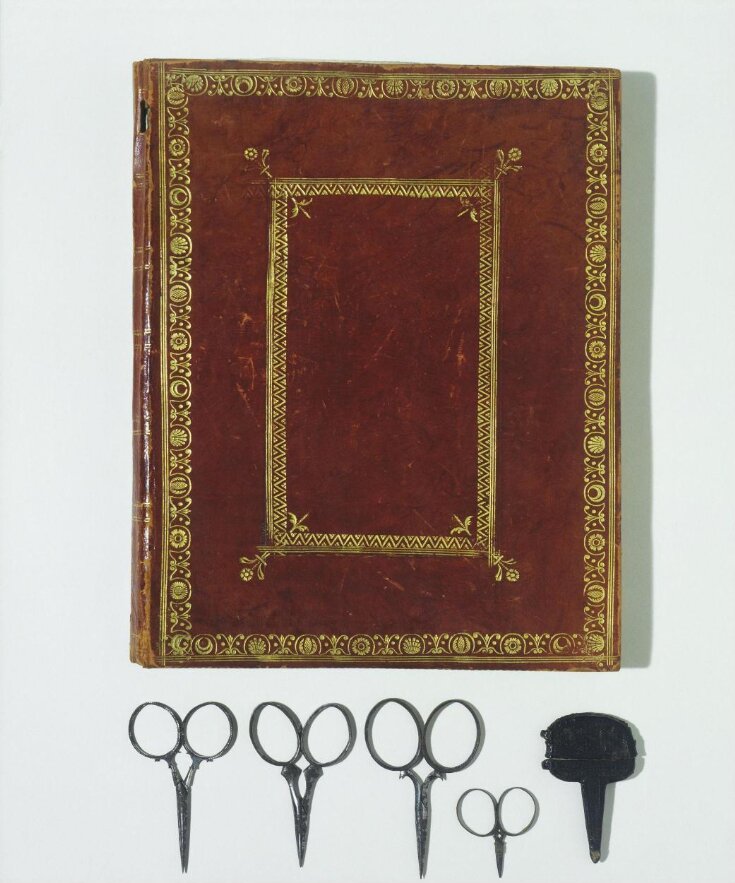

This little pair of steel scissors was found with three other small pairs housed at the back of an album containing cut-paper works. Such scissors would not have been made especially for cut-paper work, which could also be done with a knife, but were probably manufactured for needlework.

Ownership & Use

Cut-paper work was a common pastime from the late 17th century, requiring time, skill and patience in the use of small scissors such as these, knives and even pins to cut texts or images. The art was practised by the most modest of people up to the grandest in the country, including Queen Anne and Queen Victoria. A paper cutter would have needed small hands to use such scissors, and in this case they were probably used by a child, or possibly by a woman. Paper cutting was considered a suitable pastime for children and women since, like needlework, it required patient concentration. The subjects were often devotional or morally uplifting texts, but young amateurs were likely to choose less difficult subjects, such as a simple still-life or articles of household furniture. A more skilled practioner could cut animals and figures and even intricate landscapes. Interestingly, such close work was also believed to improve eyesight rather than further strain the eyes.

This little pair of steel scissors was found with three other small pairs housed at the back of an album containing cut-paper works. Such scissors would not have been made especially for cut-paper work, which could also be done with a knife, but were probably manufactured for needlework.

Ownership & Use

Cut-paper work was a common pastime from the late 17th century, requiring time, skill and patience in the use of small scissors such as these, knives and even pins to cut texts or images. The art was practised by the most modest of people up to the grandest in the country, including Queen Anne and Queen Victoria. A paper cutter would have needed small hands to use such scissors, and in this case they were probably used by a child, or possibly by a woman. Paper cutting was considered a suitable pastime for children and women since, like needlework, it required patient concentration. The subjects were often devotional or morally uplifting texts, but young amateurs were likely to choose less difficult subjects, such as a simple still-life or articles of household furniture. A more skilled practioner could cut animals and figures and even intricate landscapes. Interestingly, such close work was also believed to improve eyesight rather than further strain the eyes.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Steel |

| Brief description | Pair of paper-cutting scissors. |

| Physical description | Pair of scissors |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label | British Galleries:

Until about 1770, most paper-cuts were made with knives. Towards the end of the 18th century, miniature scissors, probably intended for needlework, came into use. The most esteemed paper cutters worked freehand, without preliminary outlines or sketches.(27/03/2003) |

| Object history | Possibly made in Woodstock, Oxfordshire |

| Summary | Object Type This little pair of steel scissors was found with three other small pairs housed at the back of an album containing cut-paper works. Such scissors would not have been made especially for cut-paper work, which could also be done with a knife, but were probably manufactured for needlework. Ownership & Use Cut-paper work was a common pastime from the late 17th century, requiring time, skill and patience in the use of small scissors such as these, knives and even pins to cut texts or images. The art was practised by the most modest of people up to the grandest in the country, including Queen Anne and Queen Victoria. A paper cutter would have needed small hands to use such scissors, and in this case they were probably used by a child, or possibly by a woman. Paper cutting was considered a suitable pastime for children and women since, like needlework, it required patient concentration. The subjects were often devotional or morally uplifting texts, but young amateurs were likely to choose less difficult subjects, such as a simple still-life or articles of household furniture. A more skilled practioner could cut animals and figures and even intricate landscapes. Interestingly, such close work was also believed to improve eyesight rather than further strain the eyes. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | E.192:39-1976 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | April 7, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest