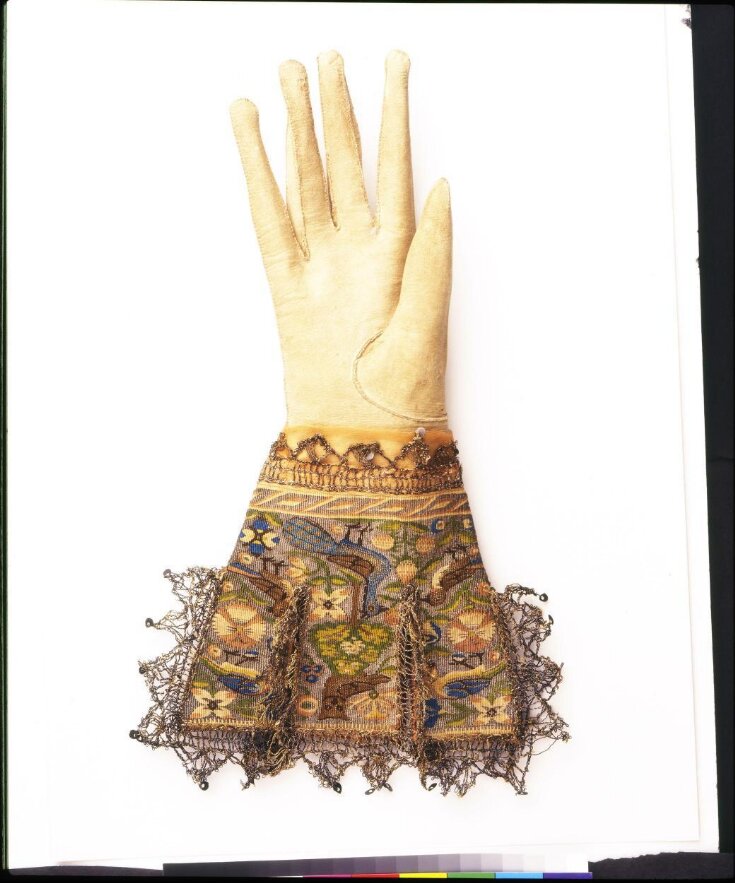

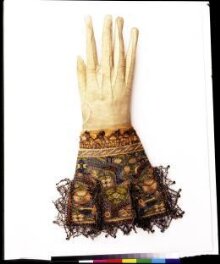

Pair of Gloves

1590-1610 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

Gloves in the 16th and early 17th centuries were much more than just an accessory to fashionable dress. The wearing or carrying of gloves by either sex was a conspicuous mark of rank and ostentation. They were worn in the hat or belt, as well as carried in the hand. Gloves were popular as gifts and were often given by a young gallant to his favourite mistress. In combat, a glove was thrown down as a gage, or challenge.

Subjects Depicted

The range of motifs on the glove, particularly the types of flowers, mixed with strawberries and birds, gives a good indication of the burgeoning interest in gardens and other natural subjects at the period.

Materials & Making

Gloves required a fine and supple leather. Doeskin and kid were the main types used. Although embroidery was the principal form of decoration for accessories, tapestry was also used. Small tapestry- woven articles, including gloves, were made by professional workshops for direct sale to the public in London shops.

Gloves in the 16th and early 17th centuries were much more than just an accessory to fashionable dress. The wearing or carrying of gloves by either sex was a conspicuous mark of rank and ostentation. They were worn in the hat or belt, as well as carried in the hand. Gloves were popular as gifts and were often given by a young gallant to his favourite mistress. In combat, a glove was thrown down as a gage, or challenge.

Subjects Depicted

The range of motifs on the glove, particularly the types of flowers, mixed with strawberries and birds, gives a good indication of the burgeoning interest in gardens and other natural subjects at the period.

Materials & Making

Gloves required a fine and supple leather. Doeskin and kid were the main types used. Although embroidery was the principal form of decoration for accessories, tapestry was also used. Small tapestry- woven articles, including gloves, were made by professional workshops for direct sale to the public in London shops.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Leather, tapestry-woven in silk and gold threads, metal bobbin lace, spangles |

| Brief description | Pair of leather gloves tapestry-woven in silks and metal threads, metal bobbin lace, probably made in Sheldon Tapestry Workshops, probably in Warwickshire, 1590-1610 |

| Physical description | Pair of gloves of white leather with gauntlet tapestry woven in silk and gold on woollen warps. 33 warp threads per in (13 per cm). With a pattern of trees, floral sprigs, strawberries with peacocks, parrots, owl and other birds. Trimmed with metal bobbin lace, vandyked and with spangles. The thumb and fork between 2nd and 3rd fingers of the left glove, A, are missing. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | Possibly made at the Sheldon tapestry workshops at Bordersley, Worcestershire or Barcheston, Warwickshire |

| Summary | Object Type Gloves in the 16th and early 17th centuries were much more than just an accessory to fashionable dress. The wearing or carrying of gloves by either sex was a conspicuous mark of rank and ostentation. They were worn in the hat or belt, as well as carried in the hand. Gloves were popular as gifts and were often given by a young gallant to his favourite mistress. In combat, a glove was thrown down as a gage, or challenge. Subjects Depicted The range of motifs on the glove, particularly the types of flowers, mixed with strawberries and birds, gives a good indication of the burgeoning interest in gardens and other natural subjects at the period. Materials & Making Gloves required a fine and supple leather. Doeskin and kid were the main types used. Although embroidery was the principal form of decoration for accessories, tapestry was also used. Small tapestry- woven articles, including gloves, were made by professional workshops for direct sale to the public in London shops. |

| Bibliographic reference | This pair of gloves was one of 13 objects investigated from 2015-2019 as part of ‘Gender, Power and Materiality in Early Modern Europe’ and ‘Gendering Interpretations’: two collaborative projects between the V&A, University of Plymouth, Vasa Museum (Stockholm), Lund University, Leiden University and the University of Western Australia. These projects aimed to recover the complex gender dynamics that made objects meaningful to early modern people, and to increase the visibility of women and LGBTQ people in museum collections.

Research on gloves as a material locus of gender and power was carried out by Professor James Daybell, Professor Svante Norrhem, Professor Susan Broomhall, Professor Jacqueline Van Gent and Dr Nadine Akkerman. Research on the V&A objects was carried out by Dr Kit Heyam.

The ubiquity of gloves as an early modern fashion accessory in Europe resulted in demand for North American deerskins, from which leather was made. The deerskin trade reshaped gender relations among the Creek Native Americans who supplied the skins: it changed men’s hunting practices, separating men from women for longer periods, and encouraged European men to seek marriage with Native American women for its strategic trade advantages.

Since all genders wore gloves in early modern Europe, and floral decoration like this was not gender-specific, it is particularly difficult to work out which gender a pair of gloves was made for. Gloves were often scented, and the smell would have had gendered connotations which are lost to us today.

Gloves enabled people to make significant gestures, which differed depending on gender. Women could seduce by dropping gloves, and men could challenge each other by throwing down a glove or using it to strike an opponent across the face. Similarly, the wearing or removal of gloves affected the erotic dynamics of male-female relationships.

These gloves have tapestry-woven gauntlets. Although they have been historically attributed to the Sheldon tapestry workshops, it may be more likely that they were produced by one of the many small weaving workshops operated in London by Flemish weavers, who were refugees from religious violence. Women were excluded from the weaving of cloth with large looms on the basis of their size and strength, but would still have been able to weave small-scale tapestry decoration like these gauntlets.

The materials with which gloves were decorated relied on women’s labour, often poorly paid. Early modern commentators were aware that the cost-effectiveness of the silk industry, which supplied embroidery thread, was enabled by the cheap labour of women and children, who harvested and unwound the cocoons. Similarly, wool-spinning enabled women to make a meagre living, but also carried ideological significance: women were encouraged to spin whether or not they needed to financially, since it was associated with virtuous productivity. However, wealthier women such as Catherine de Medici and Anne of Denmark were important investors in the silk industry.

Women were officially excluded from glovemaking guilds across Europe, though exceptions were made for widows as in other trades, and evidence suggests that some girls were apprenticed as glovers. However, the tapestry-woven gauntlets of these gloves may have provided another outlet for women’s work. Hilary L. Turner’s extensive research on the Sheldon tapestry workshops argues convincingly that the large number of attributions to these workshops – including these gloves – is often unreliable and rarely evidence-based. Instead, many of the ‘Sheldon’ tapestry items were likely produced by Flemish emigrés in small London workshops. The presence of these weavers is mainly detectable through baptism and marriage records, meaning that women are largely only visible as mothers and wives. However, there are exceptions: for example, Margaret Knutte employed three men in a weaving workshop, and Thomas the Fleming, left his weaving business and tools to his wife and two daughters. The male weavers also developed homosocial bonds with each other, as shown by Thomas White’s bequest to ‘his gossips’, Thomas Clarke and Richard Lokes.

Among the uses of gloves mentioned elsewhere, gloves also functioned as gifts at court and at weddings, and could be used as receptacles for secret messages. In one notable 1582 example, Lady Fernihurst delivered a letter concealed in her gloves to James VI of Scotland. The letter was one of a series sent by Esmé Stuart, Earl of Lennox, with whom contemporaries accused James of being in a sexual and romantic relationship: while some writers condemned this, others presented their relationship sympathetically using the tropes of medieval romance.

(Dr Kit Heyam, August 2019)

References:

Key references

· James Daybell, Svante Norrhem, Susan Broomhall, Jacqueline Van Gent and Nadine Akkerman, ‘The Gendered Power of Materiality in Early Modern English Gloves’ (forthcoming)

· John F. Richards, The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 2005)

Further reading

· Alice Clark, Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century (London: Routledge, 1919)

· Susan Frye, Pens and Needles: Women's Textualities in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010)

· Hilary L. Turner, ‘The Tapestry Trade in Elizabethan London: Products, Purchasers, and Purveyors’, The London Journal, 38:1 (2013), 18-33

· Hilary L. Turner ‘Finding the Sheldon Weavers: Richard Hyckes and the Barcheston Tapestry Works Reconsidered’, Textile History, 33:2 (2002), 137-161

· Hilary L. Turner, ‘Tapestries Once At Chastleton House And Their Influence On The Image Of The Tapestries Called Sheldon: A Reassessment’, The Antiquaries Journal, 88 (2008), 313-46

· A.J.B.Wace, ‘A pair of gloves with tapestry-woven gauntlets’, Embroideress, 42 (1932), 990-994 |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | T.145&A-1931 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 27, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest