Study from life

Photograph

1863-1864 (made)

1863-1864 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

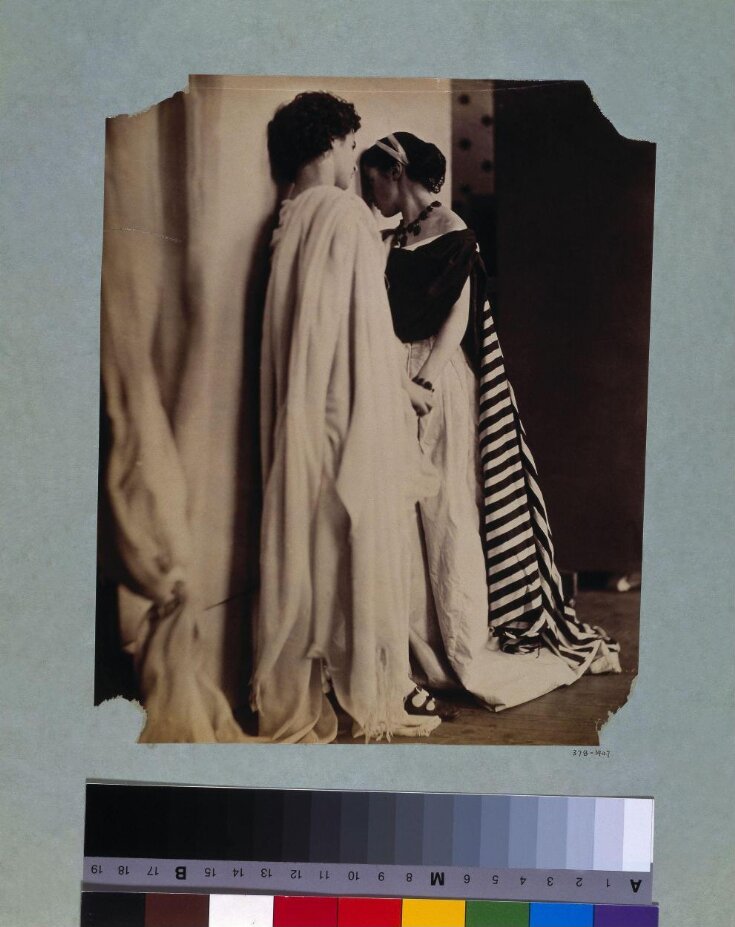

This photograph is the only known surviving print of this image, made by one the pioneers of early fine art photography. Clementina, Lady Hawarden (1822-1865) entitled her works simply Photographic Study or Study from Life.

Materials & Making

Hawarden used seven different cameras in her work, culminating in one which took plates of approximately 10x10 inch format. The photographs are albumen prints (light sensitive silver salts in an emulsion of egg white) printed from wet collodion (gun-cotton in ether) on glass negatives. A wet collodion negative consists of a sheet of glass hard-coated with a thin film. Hawarden's photographs were probably pasted into albums and torn out before entering the Museum's collections. This is why many of the corners of the pictures are irregular and torn.

Subjects Depicted

Hawarden's favoured subjects were her children, two of her daughters in particular.

Ownership & Use

The Museum has 775 photographs by Hawarden in its collection all from the donation given in 1939 by her descendant, Lady Clementina Tottenham.

Places

In 1859 Hawarden established a studio and darkroom on the first floor of her newly-built London house at 5 Princes Gardens (now demolished). It was a few hundred yards north of the South Kensington (later Victoria and Albert) Museum.

This photograph is the only known surviving print of this image, made by one the pioneers of early fine art photography. Clementina, Lady Hawarden (1822-1865) entitled her works simply Photographic Study or Study from Life.

Materials & Making

Hawarden used seven different cameras in her work, culminating in one which took plates of approximately 10x10 inch format. The photographs are albumen prints (light sensitive silver salts in an emulsion of egg white) printed from wet collodion (gun-cotton in ether) on glass negatives. A wet collodion negative consists of a sheet of glass hard-coated with a thin film. Hawarden's photographs were probably pasted into albums and torn out before entering the Museum's collections. This is why many of the corners of the pictures are irregular and torn.

Subjects Depicted

Hawarden's favoured subjects were her children, two of her daughters in particular.

Ownership & Use

The Museum has 775 photographs by Hawarden in its collection all from the donation given in 1939 by her descendant, Lady Clementina Tottenham.

Places

In 1859 Hawarden established a studio and darkroom on the first floor of her newly-built London house at 5 Princes Gardens (now demolished). It was a few hundred yards north of the South Kensington (later Victoria and Albert) Museum.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Study from life (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Albumen print from a wet collodion on glass negative |

| Brief description | Photographic Study - Clementina and Isabella Grace |

| Physical description | 5 Princes Gardens, interior: first floor, front: screens (with drapes): starred wall-paper: floor-boards: Clementina (right profile, face nearly turned away), standing, right hand holding left hand of Isabella Grace (left profile), who is standing, resting forehead on screen. Both in fancy dress (Orientalist or classical). Clementina is wearing a short curly wig. The mantelpiece, with ?pictures on it, is visible between the screens in the background. Inscriptions (verso): 10 (written over) No 226 Inscription (verso of mount): (X614-)226 |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Given by Lady Clementina Tottenham, granddaughter of the photographer |

| Object history | Photograph taken in London by Clementina, Lady Hawarden (born in Cumbernauld, near Glasgow, 1822, died in London, 1865) |

| Historical context | From departmental notes 'Clementina, Lady Hawarden (Untitled) Photographic Study (or) Study from Life (D.658) c.1863-c.1864 5 Princes Gardens, interior: first floor, front: screens (with drapes): starred wall-paper: floor-boards: Clementina (right profile, face nearly turned away), standing, right hand holding left hand of Isabella Grace (left profile), who is standing, resting forehead on screen. Both in fancy dress (Orientalist or classical). Clementina is wearing a short curly wig. The mantelpiece, with ?pictures on it, is visible between the screens in the background. Inscriptions (verso): 10 (written over) No 226 Inscription (verso of mount): (X614-)226 236 x 192 mm PH 378-1947 Literature: ed. Mark Haworth-Booth, The Golden Age of British Photography, 1984, p.123.Microfilm: 3.18.92; V&A Picture Library negativE no. GG 4954 (reference no. 42464). The Golden Age of British Photography (travellir exhibition), Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984-8~ This comment applies to photographs D.640 to D.667 and D.699 to D.705. As seen in these photographs, Lady Hawarden and her daughters appear to have been fond of Oriental costumes and settings. The exotic dress and tent-like atmosphere (an artful conversion of the drawing room) lend to the suggestion of harem scenes and add a frisson of eroticism to the tableaux. In painting and in photography, Orientalist genre made it possible to depict sensuality on the premise of presenting quasi-ethnographic information about the customs of the East. In Britain the popularity of this genre was well-established by the 1850s, particularly through the work of John Frederick Lewis, who painted many harem scenes featuring beautiful young women who, in spite of their exotic costumes, were essentially the 'English rose' type. [With thanks to Harley Preston, formerly National Maritime Museum, London, and Kathy McLauchlan, Education Services, V&A Museum.] The photographer Roger Fenton also used non-Oriental models in his 'Nubian Series', exhibited at the Photographic Society of London in 1859, which may have prompted Lady Hawarden's variations on this theme. [See Valerie Lloyd, Roger Fenton: Photographer of the 1850's, London 1988 for reproductions.]As seen in these photographs, Lady Hawarden and her daughters appear to have been fond of Oriental costumes and settings. The exotic dress and tent-like atmosphere (an artful conversion of the drawing room) lend to the suggestion of harem scenes and add a frisson of eroticism to the tableaux. In painting and in photography, Orientalist genre made it possible to depict sensuality on the premise of presenting quasi-ethnographic information about the customs of the East. In Britain the popularity of this genre was well-established by the 1850s, particularly through the work of John Frederick Lewis, who painted many harem scenes featuring beautiful young women who, in spite of their exotic costumes, were essentially the 'English rose' type. [With thanks to Harley Preston, formerly National Maritime Museum, London, and Kathy McLauchlan, Education Services, V&A Museum.] The photographer Roger Fenton also used non-Oriental models in his 'Nubian Series', exhibited at the Photographic Society of London in 1859, which may have prompted Lady Hawarden's variations on this theme. [See Valerie Lloyd, Roger Fenton: Photographer of the 1850's, London 1988 for reproductions.]The exotic dress and tent-like atmosphere (an artful conversion of the drawing room) lend to the suggestion of harem scenes and add a frisson of eroticism to the tableaux. In painting and in photography, Orientalist genre made it possible to depict sensuality on the premise of presenting quasi-ethnographic information about the customs of the East. In Britain the popularity of this genre was well-established by the 1850s, particularly through the work of John Frederick Lewis, who painted many harem scenes featuring beautiful young women who, in spite of their exotic costumes, were essentially the 'English rose' type. [With thanks to Harley Preston, formerly National Maritime Museum, London, and Kathy McLauchlan, Education Services, V&A Museum.] The photographer Roger Fenton also used non-Oriental models in his 'Nubian Series', exhibited at the Photographic Society of London in 1859, which may have prompted Lady Hawarden's variations on this theme. [See Valerie Lloyd, Roger Fenton: Photographer of the 1850's, London 1988 for reproductions.]In painting and in photography, Orientalist genre made it possible to depict sensuality on the premise of presenting quasi-ethnographic information about the customs of the East. In Britain the popularity of this genre was well-established by the 1850s, particularly through the work of John Frederick Lewis, who painted many harem scenes featuring beautiful young women who, in spite of their exotic costumes, were essentially the 'English rose' type. [With thanks to Harley Preston, formerly National Maritime Museum, London, and Kathy McLauchlan, Education Services, V&A Museum.] The photographer Roger Fenton also used non-Oriental models in his 'Nubian Series', exhibited at the Photographic Society of London in 1859, which may have prompted Lady Hawarden's variations on this theme. [See Valerie Lloyd, Roger Fenton: Photographer of the 1850's, London 1988 for reproductions.]The photographer Roger Fenton also used non-Oriental models in his 'Nubian Series', exhibited at the Photographic Society of London in 1859, which may have prompted Lady Hawarden's variations on this theme. [See Valerie Lloyd, Roger Fenton: Photographer of the 1850's, London 1988 for reproductions.]' |

| Summary | Object Type This photograph is the only known surviving print of this image, made by one the pioneers of early fine art photography. Clementina, Lady Hawarden (1822-1865) entitled her works simply Photographic Study or Study from Life. Materials & Making Hawarden used seven different cameras in her work, culminating in one which took plates of approximately 10x10 inch format. The photographs are albumen prints (light sensitive silver salts in an emulsion of egg white) printed from wet collodion (gun-cotton in ether) on glass negatives. A wet collodion negative consists of a sheet of glass hard-coated with a thin film. Hawarden's photographs were probably pasted into albums and torn out before entering the Museum's collections. This is why many of the corners of the pictures are irregular and torn. Subjects Depicted Hawarden's favoured subjects were her children, two of her daughters in particular. Ownership & Use The Museum has 775 photographs by Hawarden in its collection all from the donation given in 1939 by her descendant, Lady Clementina Tottenham. Places In 1859 Hawarden established a studio and darkroom on the first floor of her newly-built London house at 5 Princes Gardens (now demolished). It was a few hundred yards north of the South Kensington (later Victoria and Albert) Museum. |

| Bibliographic reference | Literature: ed. Mark Haworth-Booth, The Golden Age of British Photography, 1984, p.123.Microfilm: 3.18.92; V&A Picture Library negativE no. GG 4954 (reference no. 42464). |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 378-1947 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 27, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest