| Bibliographic references | - Calloway, Stephen. Aubrey Beardsley. London: V & A Publications, 1998. 224pp, illus. ISBN: 1851772197.

- Victoria & Albert Museum Department of Prints and Drawings and Department of Paintings, Accessions 1932. London: HMSO, 1933

- Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley : a catalogue raisonne. New Haven : Yale University Press, [2016] 2 volumes (xxxi, [1], 519, [1] pages; xi, [1], 547, [1] pages) : illustrations (some color) ; 31 cm. ISBN: 9780300111279

The entry is as follows:

908

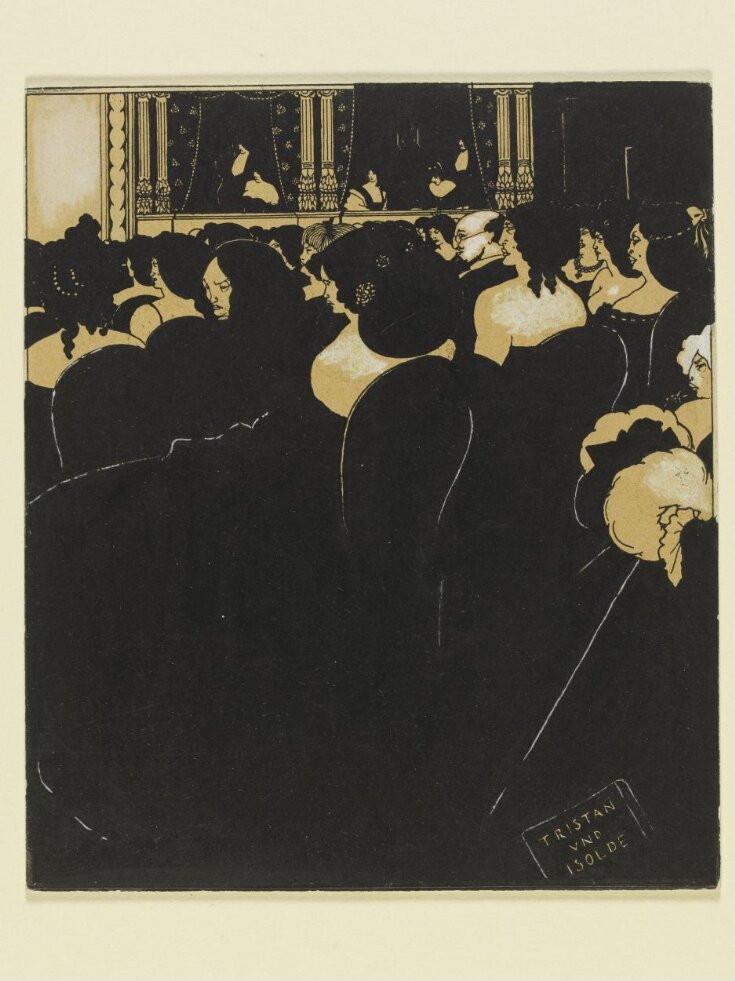

The Wagnerites

May 1893 - late June 1894

Victoria and Albert Museum (E.136-1932)

Pen, brush and Indian ink over traces of pencil with touches of white gouache laid down on (discoloured) artist’s board secured to backing with slotted hinges; 8 1/8 x 7 inches (206 x 178 mm).

INSCRIPTIONS: Recto inscribed by artist in pencil and kept in reserve: TRISTRAM / UND / ISOLDE [white gouache highlighting on downstroke of the R and the Ns.]

FLOWERS: Stylised rose (love, passion).

PROVENANCE: Given by the artist to Joseph Pennell; bequeathed to Elizabeth Pennell; Sotheby’s sale 15-17 February 1932 (500); bt. Hardie; bt. Victoria and Albert Museum in 1932.

EXHIBITION: Paris 1960-1 (17); London 1966-8 (405, London only), 1971 (291); Tokyo 1983 (64); Munich 1984 (159); Rome 1985 (17.4); London 1993 (106).

LITERATURE: ‘World’ 18 November 1894 (p. 26); ‘Courrier Francais’ 10 February 1895 (Supplement, p. 13); ‘Book Buyer’ February 1895 (p. 28); Vallance 1897 (p.206); Shaw 1898 (p. v); Blanche 25 March 1898 (p. 8); Vallance 1909 (no. 89.xx); Pennell 1921b (pp. 12, 16); king 1924 (pp. 40-1); Pennell 1925 (pp. 214, 217); Burdett 1925 (p.117); Gallatin 1945 (no. 915); Mix 1960 (p. 127); Reade 1967 (p. 347, n. 364); Brophy 1969 (p. 32); ‘Letters’ 1970 (pp. 71, 75); Brophy 1976b (p. 67); Clark 1979 (pp. 29-30); Gray ‘La Revue Blanche’ 1980 (n.p.); Furness 1982 (pp. 38, 53); Wilson 1983 (plate 22); Heyd 1986 (pp. 173-7); Fletcher 1987 (p.105); Hefting 1989 (p. 10); Cowling 1989 (pp. 82, 333); Zatlin 1990 (pp. 87, n. 3); Samuels Lasner 1995 (no. 65); Snodgrass 1995 (pp. 263, 266); Jempson 1996 (p. 66); Zatlin 1997 (p. 79); Samuels Lasner 1998b (no. 118); Sutton 2002 (pp. 19, 20, 27, 44, 90-103, 106, 108, 109-15); Sturgis 2005 (pp. 147-9, 155-8).

REPRODUCED: ‘Yellow Book’, Volume III, October 1894 (p. 55); ‘World’ 18 November 1894 (p. 26); ‘Courrier Francais’ 23 December 1894 (p. 6); Symons 1898 (plate 4); ‘Early Work’ 1899 (no. 65); ‘Pan’ (Berlin) V.ii (1899/1900, p. 262); ‘Best of Beardsley’ 1948 (plate 30); Reade 1967 (plate 366); Clark 1979 (plate 39); Wilson 1983 (plate 22).

In an unpublished letter of 5 September 1894 (formerly owned by Kenneth A. Lohf), Beardsley said that this drawing, which he had begun in Paris in May 1893, was still in progress when the June 1894 issue of the ‘Yellow Book’ went to press (Christie’s [New York] sale 20 November 1992, excerpted in lot 14). In early October 1894, he told Frederick Evans to ‘Look out for No 3 of the Y.B. By general consent my best things are in it, particularly one called ‘The Wagnerites’ (‘Letter’ 1970, p. 75). One sign of this extended work is the liberal use of white gouache to correct mistakes on the muff and the back of the chair at the centre; the retouching made it one of his only drawings less effective than prints made from it.

Beardsley’s visual inspiration was dual: in Western art, most probably Degas’ ‘The Orchestra of the Opera, Rue Le Peletier’ (1868-9, Musee d’Orsay, Paris) and ‘The Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer’s Opera Robert le Diable’ (1876, Victoria and Albert Museum, London), paintings that cut off much of the stage and focus on the orchestra from the viewpoint of the first row; Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1892 colour lithograph ‘Le Divan Japonais’, which focuses on the spectators at the bar rather than Yvette Guilbert who sings on the stage; and Walter Sickert’s paintings of the theatre (on Sickert, see Sutton 2002, p. 102). An influence from Eastern art was Japanese woodblock prints of theatre interiors (Zatlin 1997, p. 79). ‘The Wagnerites’ is a theatre scene dramatically different from contemporary British depictions, in which interest is divided between the stage and the audience. In contrast, Beardsley concentrated solely on the audience and distinguished each jaded face with its own expression of hauteur; by contrasting these females with a sensitive-faced man, Beardsley underscored the women’s self-absorption (Zatlin 1997, p.79). Beardsley may have influenced Sickert in return: the painter’s focus on the audience rather than the stage begins in his painting ‘The Gallery at the Old Bedford’ (c.1895, Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool, UK). Moreover, it is possible that Sickert included his young friend: the tall think figure walking into the gallery at the viewer’s right has the same colouring that the painter gave Beardsley’s face in his 1894 portrait, showing the artist leaving the unveiling ceremony of a memorial bust of Keats at Hampstead Parish Church (Tate Collection, London).

Although the Pennels claim that the drawing was begun one Saturday night in May 1894 in Paris after a performance of ‘Tristram und Isolde’, Jempson disproves their assertion (Pennell 1921b, p. 12; Jempson 1996, p. 66; Sutton 2002, p.93, n. 14). A cited letter formerly owned by Kenneth Lohf (cited above) lends credence to the Pennells’ dating, but instead of ‘Tristram und Isolde’, Beardsley might have seen, Sutton says, ‘parts of ‘Das Rheingold’... on 6 May 1893 and [all of] ‘Die Walkure’... on 12 May’ (2002, p. 93, n. 14). Beardsley did see ‘Tristram und Isolde’ on 30 June 1894, having notified F. H. Evans three days earlier that he would be ‘reclining in the unmusical stalls’ (‘Letters’ 1970, p.71 [27 June 1894]; see also for example nos. 251-3, 267, 504 above, 957 below).

The vogue for Wagner had been increasing since the 1860s. By the 1880s, it was a highly diverse phenomenon when, for example, Les Vingt, the avant-garde Belgian art group, organised lectures and concerts to coincide with exhibitions. In one lecture the novelist and critic Catulle Mendes spoke on the ‘Vague Wagnerienne’ (Hefting 1989, p. 10). Beardsley was arguably the most successful visual interpreter of Wagner’s music, and this drawing is his ‘most successful transposition of Wagner’s eroticism’; the sensual women are ‘collectively Isolde… an Isolde who is “gulping” the love potion’, even as the sensual diabolism of the music in ‘reflected in the heads and naked shoulders of his admirers’ (Brophy 1969, p.32; Clark 1979, pp. 29-30). Beardsley froze one woman in the act of turning to look at a late arrival and frowning appraisingly, a figure Reade tells us Ella D’Arcy identified for Mix as a portrait of Elizabeth Barrett Browning (RA; Mix 1960, p. 127). Reade, Wilson and Fletcher argue that Beardsley must have been delighted in the irony of contrasting the opera about idealised love with an audience of worldly looking and disdainful women, and that he satirised ‘those wealthy and worldly opera-goers for whom the opera is simply another part of the fashionable social round and who have no true interest in, or understanding of, the music’ (1967, p.347 n. 364; 1983, plate 22; 1987, p.105). Sutton believes that the drawing is more ambivalent, presenting the viewer with clues to detect whether ‘the image was conceived as a scathing critique of contemporary Wagnerites, as an amused commentary on the disjunction between audience and art-work, or as an approving delineation of the decadence, the sensuality, of Wagner’s music and its admirers’ (2002, pp. 99-100)

The drawing may represent Beardsley’s response to the anti-semitic Wagner of ‘Judaism in Music’ (1850); its centrally placed Jewish man demonstrates that the figure of the Jew can be a subject for art and may appear in an audience appreciating Wagner. In fact, caricatures of Wagner and his audience flourished throughout Europe; there is an example by Willette in ‘Le Courrier Francais’ in 1891 and one in ‘Vienne Kikeriki’ in 1882 (Heyd 1986, pp. 173-7). In addition, Beardsley mocks the women’s limited emotional involvement with the opera by contrasting them with the Jewish man, who is recognisable by the physiognomical lack of balance in his features. Analysing the type in W. P. Frith’s ‘Derby Day’ (1858, Tate Collection, London), Cowling points out that Frith lumps the Jew with the Irishman and the Scotsman in their ‘moral ugliness’; their ‘noses are bulbous; their mouths wide and full, with heavy sensual underlips. Their eyes - the most spiritual feature of all - are comparatively small. The flesh of their faces looks coarse-grained and suitably dissipated. All have heavy faces… {An] avariciousness suggested by the absorption of the Jew’ (Cowling 1989, p. 333). Beardsley’s Jewish man has a nose that thoroughly disbalances his face. In the physiognomer Eden Warwick’s 1864 classification, for example, the Jewish nose is ‘very convex… from the eyes to the tip. It is thin and sharp. It indicates considerable Shrewdness in worldly matters; a deep insight into character, and facility of turning that insight to profitable account’ [quoted in Cowling, p. 82]). His glasses and mild glance typify him also as a womanly man - cultured, interested in the arts and therefore domesticated and effete - a concept in the air during the 1890s (Zatlin 1990, p.87, n. 3). Indeed, Brophy believes he is a homosexual (1969, p. 32); it might be a caricature of Reginald Turner, a friend of Oscar Wilde’s, Robert Ross or More Adey.

Beardsley may have had personal reasons for including this man: Jewish people were among his friends and acquaintances. He socialised with Oscar Wilde’s friends Ada and Ernest Leverson and was friendly with Ernest’s cousin Marguerite and her husband Brandon Thomas, with whom in early February 1894 Beardsley began writing a play (NYU-FLMC, Box 180.6, chapter 17, p. 267; Brandon-Thomas 1955, p. 166; Christie’s 12 November 1999 [8], als Mabel Beardsley to ‘Helen’). The drawing may acknowledge ‘the baleful attraction which Wagner had for many Jews’ (Furness 1982, pp. 38, 53). Or the figure may be intended to counter the casual anti-semitic remarks made by people he knew. Joseph Pennell, for example, makes uncomplimentary remarks about Jews in his letters and imitates an Eastern European (Immigrant Jewish) accent when he describes certain American collectors ‘incited to collect not for beauty, or excellence of craftsmanship, but because the book is rare and, therefore. “Tink vat it vill pring in de auction ven yer has to sell it!”’ (Pennell, 1925, p. 214; see also Pennell 1921b, p. 16; Pennell attributes the same feelings to Whistler: ‘During Whistler’s frequent and long visits to Heinemann [his publisher, of Jewish heritage] at this period there were other strange encounters - with Beerbohm, Frank Harris, Shorter, Rothenstein - how he hated Jews’ [1925, p. 214]). Beardsley’s old friend A. W. King believes the audience in this drawing to be ‘exactly like the [real audience] groups of clever, ugly, rich, Anglicized Germans and Austrians, with a jew [sic] or two thrown in’; the literary critic Osbert Burdett characterised that audience as ‘crowded with rich and lecherous cosmopolitans’, the noun a code word for Jews (1924, pp. 40-1; 1925, p.117; for discussion of anti-semitism in late nineteen-century Wagnerism, see Sutton 2002, pp. 109-15).

According to Reade, ‘the bold break-up of the crowded scene into a comparatively few areas of black and white to represent the darkness of the auditorium’, makes this one of the best known of Beardsley’s drawings (1967, p. 347, n. 364). The presentation of the illusion of shadow, without shading may have been sparked by the influence of Japanese woodblock prints or the shadow theatre designs of the Nabi artist Henri Riviere (1864-1951). On the back of the drawing (now inaccessible), Joseph Pennell wrote ‘THIS IS ONE OF THE FINEST DRAWINGS A.B. EVER MADE, and it had much to do with making his reputation in France. It was drawn in 1894 and first published in the Yellow Book, vol III, and I think in the Courrier Francais. JOSEPH PENNELL’ (Sotheby’s [London] sale 29 February 1930 [lot 500]). Brophy believes that George Bernard Shaw entitled his essay ‘The Perfect Wagnerite’ after this drawing and had it in mind when he sarcastically dedicated his essay, ‘to those enthusiastic admirers of Wagner who are unable to follow his ideas… [but who are] devoted to Wagner merely as a slave is devoted to his master, sharing a few elementary ideas, appetites and emotions with him, and, for the rest, reverencing his superiority without understanding it (1976b, p. 67; Shaw 1898, p. v).

Critical response to this drawing was mixed, even among Beardsly’s friends. The French painter Jacques-Emile Blanche may have had it in mind when he declared ‘the women of Aubrey Beardsley… answer to a “Yellow Book” type which has happily no real representative in this world’ (25 March 1898, p. 8). In contrast, John Gray finds that ‘Wagnerian concerts were thronged with his characters’ (1980, n.p.). And Herbert Small, a reviewer for the American magazine ‘Book Buyer’, describes this drawing as swarming ‘with horrible women, but which… is satire as terrific and Hogarth’s’ (February 1895, p. 28). Other critics were less complimentary. The ‘World’, for example, states, this is ‘one of his unnecessarily vulgar fancies. [More appropriately] he might just as well have labelled it … Bedlamites’ (18 November 1894, p. 26; Sutton 2002, pp. 94-9 discusses Wagner’s appeal to women in the 1890s). Despite these comments that suggest the anti-Beardsley bandwagon ever ready to blare, surprisingly few critics wrote about this work.

Five of Beardsley’s drawings, including this one, were reproduced in the programme for the 1 November 1983 performance of ‘Tannhauser’ and the cycle of Wagner’s opera performed that season at the Bayerische Staatsoper, Germany (ABS; see also nos. 195 above and 1064 below)

Along with originals and prints by French and other European artists, the drawing, titled in French ‘A une representation de Tristran et Iseult - Wagnerites and Wagneriennes’, was offered for sale (unpriced) on 10 February 1895 in a supplement of ‘Courrier Francais’ (Pennell 1925, p. 217). And it influenced fashion of the 1960s, in particular bare-backed cocktail dresses by the couturiers Trigere and Halston (Life Magazine, 24 February 1967, pp. 47-51).

|