Brooch

1953 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

In the early post-war years jewellery began to be accepted as an art form or ‘wearable art’, expressing the character of the wearer as much as that of the designer. In liberating themselves from the conventions of traditional jewellery, designers looked back to the modernist principles of the Bauhaus and to earlier avant-garde art movements such as Surrealism, Cubism and Constructivism. This allowed them to create unique designs, often with a sculptural quality.

Jewels of this period are abstract in design, though they may use, or refer to traditional motifs, such as here the fish. Stones have unconventional shapes and their arrangement is often asymmetrical.

Elisabeth Treskow’s early jewellery follows the Bauhaus principles. In the 1920s her interest in ancient jewellery transformed her designs. In many of her jewels she incorporated ancient gems. She owned a large collection of ancient jewellery which she bequeathed to the Museum für Angewandte Kunst, in Cologne.

Treskow fascinated by the techniques used by ancient goldsmiths, in particular the Etruscans, explored the technique of granulation in which minute grains of gold are applied to the surface without the use of solder. Treskow wrote about her experiences with granulation, and acknowledged Johann Michael Wilm from Hamburg, who in 1920 was the first to solve the mystery how the Etruscans made granulation. Treskow admits her attempts were not successful until 1930. It was not until 1936 that she had first heard a lecture by H. A. P. Littledale, who patented his re-discovered method of granulation in 1933.

Elisabeth Treskow made jewellery as well as liturgical silver. She was trained in Essen, Hagen and Schwäbisch-Gmünd, and had her first workshop in 1919. Between 1948 and 1964 she taught at the Werkkunstschule in Cologne, and inspired generations of goldsmiths.

Jewels of this period are abstract in design, though they may use, or refer to traditional motifs, such as here the fish. Stones have unconventional shapes and their arrangement is often asymmetrical.

Elisabeth Treskow’s early jewellery follows the Bauhaus principles. In the 1920s her interest in ancient jewellery transformed her designs. In many of her jewels she incorporated ancient gems. She owned a large collection of ancient jewellery which she bequeathed to the Museum für Angewandte Kunst, in Cologne.

Treskow fascinated by the techniques used by ancient goldsmiths, in particular the Etruscans, explored the technique of granulation in which minute grains of gold are applied to the surface without the use of solder. Treskow wrote about her experiences with granulation, and acknowledged Johann Michael Wilm from Hamburg, who in 1920 was the first to solve the mystery how the Etruscans made granulation. Treskow admits her attempts were not successful until 1930. It was not until 1936 that she had first heard a lecture by H. A. P. Littledale, who patented his re-discovered method of granulation in 1933.

Elisabeth Treskow made jewellery as well as liturgical silver. She was trained in Essen, Hagen and Schwäbisch-Gmünd, and had her first workshop in 1919. Between 1948 and 1964 she taught at the Werkkunstschule in Cologne, and inspired generations of goldsmiths.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Gold decorated with granulation and set with a sapphire, diamonds and a baroque pearl |

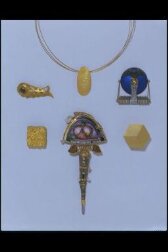

| Brief description | Brooch in the form of a fish, gold decorated with granulation set with diamond, sapphire and pearl. Designed and made by Elizabeth Treskow, Cologne, 1953. |

| Physical description | In the form of a fish, the eye suggested by a sapphire set into a depression lined with granulation, the scales by diamonds set into lozenges of granulation. A baroque pearl is set into the upper part of the tail fin. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | ET 750 in a rectangle. Note 1) Makers's mark; Engraved on back of brooch |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | In the early post-war years jewellery began to be accepted as an art form or ‘wearable art’, expressing the character of the wearer as much as that of the designer. In liberating themselves from the conventions of traditional jewellery, designers looked back to the modernist principles of the Bauhaus and to earlier avant-garde art movements such as Surrealism, Cubism and Constructivism. This allowed them to create unique designs, often with a sculptural quality. Jewels of this period are abstract in design, though they may use, or refer to traditional motifs, such as here the fish. Stones have unconventional shapes and their arrangement is often asymmetrical. Elisabeth Treskow’s early jewellery follows the Bauhaus principles. In the 1920s her interest in ancient jewellery transformed her designs. In many of her jewels she incorporated ancient gems. She owned a large collection of ancient jewellery which she bequeathed to the Museum für Angewandte Kunst, in Cologne. Treskow fascinated by the techniques used by ancient goldsmiths, in particular the Etruscans, explored the technique of granulation in which minute grains of gold are applied to the surface without the use of solder. Treskow wrote about her experiences with granulation, and acknowledged Johann Michael Wilm from Hamburg, who in 1920 was the first to solve the mystery how the Etruscans made granulation. Treskow admits her attempts were not successful until 1930. It was not until 1936 that she had first heard a lecture by H. A. P. Littledale, who patented his re-discovered method of granulation in 1933. Elisabeth Treskow made jewellery as well as liturgical silver. She was trained in Essen, Hagen and Schwäbisch-Gmünd, and had her first workshop in 1919. Between 1948 and 1964 she taught at the Werkkunstschule in Cologne, and inspired generations of goldsmiths. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.1-1988 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 3, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSON