The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries

Tapestry

1430s (made)

1430s (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

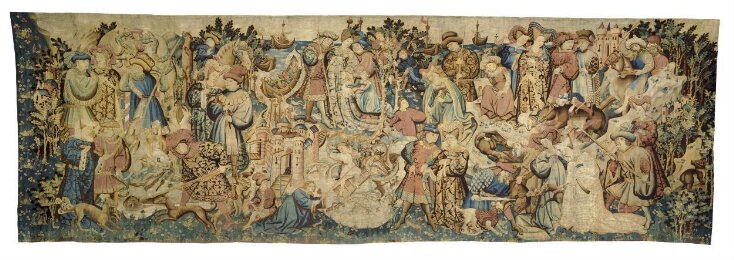

In the 15th century, tapestries provided colour, warmth and draught-proofing in bleak rooms with stone walls. Those with narratives also provided entertainment and interest for the household and guests at a time of low literacy, when images were extremely important.

The group of four Devonshire Hunting Tapestries of which this is one example belonged, until they came to the Museum in 1957, to the dukes of Devonshire. Large tapestries were not produced in England in the 15th century and had to be imported. A number of towns or cities in the southern Netherlands had workshops and it was in one of these that the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries were made. The earliest history of the tapestries is unknown but they were identified as being at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire in the 16th century, from an inventory compiled in 1601 for the Countess of Shrewsbury. This celebrated and four-times married noblewoman had Hardwick Hall built and furnished to her taste, which evidently included the15th-century hunting tapestries.

The hunt was a particularly powerful theme and would have been a familiar pastime to many of the high-born individuals and families who owned tapestries. Hunting was both a sport and an important source of food. The otter hunt shown in this tapestry is rather gruesome, particularly to the modern eye. Otters were hunted not to eat but for their skins and because they consumed fish that were required for the table. Swan meat was, however, highly desirable and here boys are seen robbing a swan’s nest. At one time, swans could be owned only by the royal family, but as they gradually escaped into the wild they became fair game for other people, although theoretically they could only be hunted by licence. A ferocious bear hunt is seen on the right with Middle Eastern figures wearing turbans participating.

The composition is made up of numerous scenes that each make sense separately. This device was often used in tapestry design so that if, as often happened, the tapestry were cut up or altered - for example, to go round a doorway or fit a smaller room - the narrative would still make sense.

The group of four Devonshire Hunting Tapestries of which this is one example belonged, until they came to the Museum in 1957, to the dukes of Devonshire. Large tapestries were not produced in England in the 15th century and had to be imported. A number of towns or cities in the southern Netherlands had workshops and it was in one of these that the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries were made. The earliest history of the tapestries is unknown but they were identified as being at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire in the 16th century, from an inventory compiled in 1601 for the Countess of Shrewsbury. This celebrated and four-times married noblewoman had Hardwick Hall built and furnished to her taste, which evidently included the15th-century hunting tapestries.

The hunt was a particularly powerful theme and would have been a familiar pastime to many of the high-born individuals and families who owned tapestries. Hunting was both a sport and an important source of food. The otter hunt shown in this tapestry is rather gruesome, particularly to the modern eye. Otters were hunted not to eat but for their skins and because they consumed fish that were required for the table. Swan meat was, however, highly desirable and here boys are seen robbing a swan’s nest. At one time, swans could be owned only by the royal family, but as they gradually escaped into the wild they became fair game for other people, although theoretically they could only be hunted by licence. A ferocious bear hunt is seen on the right with Middle Eastern figures wearing turbans participating.

The composition is made up of numerous scenes that each make sense separately. This device was often used in tapestry design so that if, as often happened, the tapestry were cut up or altered - for example, to go round a doorway or fit a smaller room - the narrative would still make sense.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Titles |

|

| Materials and techniques | Tapestry-woven |

| Brief description | Swan and Otter Hunt, from The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, 15th century. |

| Physical description | Swan & Otter Hunt, tapestry. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax payable on the estate of the 10th Duke of Devonshire and allocated to the Victoria and Albert Museum |

| Object history | Cut into strips nad arbitrarily joined as curtains, these rare fifteenth century tapestries were discovered in the Long Gallery at Hardwick Hall in the late 19th century. The Duke of Devonshire sent the pieces to this Museum in 1900 for examination and reassembly, and they were sewn together as four large hangings by the Ladies' Decorative Needlework Society in Sloane Street. In need of cleaning and repair by 1950, The Deer Hunt was washed and restored, with much reweaving, in Paris. On the death of the 10th Duke of Devonshire, the tapestries were acquired for the Nation. Between 1958 and 1966 the other three pieces were cleaned and restored at a tapestry workshop in Haarlem. Few tapestries of this size and date have survived centuries of use. It is not known where these particular tapestries were made; but so many fine tapestries of this period came from Arras that the name became synonmous with tapestry in England. The four pieces actually come from slightly differen sets, as can most clearly be seen in comparing the height of the Boar and Bear Hund and the scale of its figures with the adjacent Falconry. (Taken directly from the introductory label taken down in August 2006) |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | In the 15th century, tapestries provided colour, warmth and draught-proofing in bleak rooms with stone walls. Those with narratives also provided entertainment and interest for the household and guests at a time of low literacy, when images were extremely important. The group of four Devonshire Hunting Tapestries of which this is one example belonged, until they came to the Museum in 1957, to the dukes of Devonshire. Large tapestries were not produced in England in the 15th century and had to be imported. A number of towns or cities in the southern Netherlands had workshops and it was in one of these that the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries were made. The earliest history of the tapestries is unknown but they were identified as being at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire in the 16th century, from an inventory compiled in 1601 for the Countess of Shrewsbury. This celebrated and four-times married noblewoman had Hardwick Hall built and furnished to her taste, which evidently included the15th-century hunting tapestries. The hunt was a particularly powerful theme and would have been a familiar pastime to many of the high-born individuals and families who owned tapestries. Hunting was both a sport and an important source of food. The otter hunt shown in this tapestry is rather gruesome, particularly to the modern eye. Otters were hunted not to eat but for their skins and because they consumed fish that were required for the table. Swan meat was, however, highly desirable and here boys are seen robbing a swan’s nest. At one time, swans could be owned only by the royal family, but as they gradually escaped into the wild they became fair game for other people, although theoretically they could only be hunted by licence. A ferocious bear hunt is seen on the right with Middle Eastern figures wearing turbans participating. The composition is made up of numerous scenes that each make sense separately. This device was often used in tapestry design so that if, as often happened, the tapestry were cut up or altered - for example, to go round a doorway or fit a smaller room - the narrative would still make sense. |

| Associated objects | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | T.203-1957 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | January 22, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest