Jug

ca. 1780 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

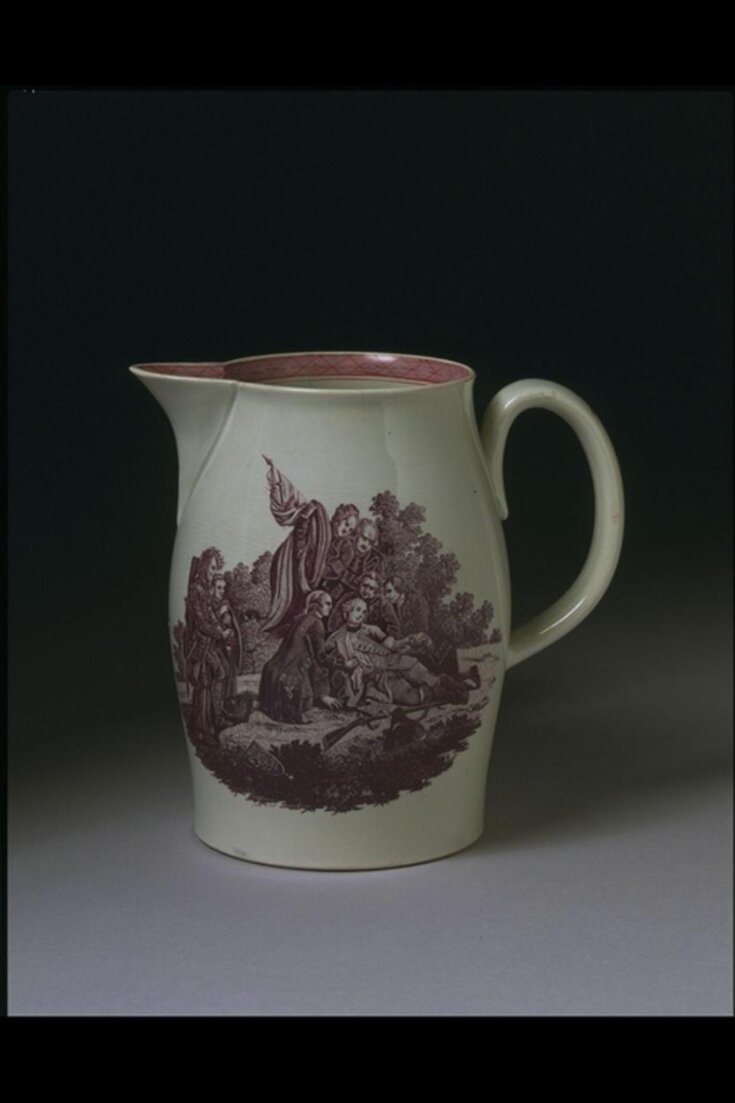

Smallish creamware jugs may have been used for purposes other than serving beer - for example, for milk. The swelling barrel-shaped body with flaring foot and rim was one of the most popular jug forms in the last quarter of the 18th century.

Time

The taking of Quebec in 1759 by the British commander James Wolfe was the turning-point in a long-running struggle between the French and British for control of North America. The death of Wolfe at the moment of victory - like that of Nelson in 1805 at Trafalgar - caught the public imagination and turned him into a great hero. The engraving of Benjamin West's painting of 1771- The Death of General Wolfe - became the fastest-selling print of its time on publication in 1776. Yet retrospective representations of historical events are not always what they seem. When Wolfe was dying on the battlefield - the Heights of Abraham at Montreal - he asked his best friend, Colonel John Hale, to take home and present the despatches (the official report of the battle) to George II, who in turn asked Hale to raise a new regiment, the 17th Lancers. Later, Colonel Hale declined to pay the 100 guineas 'admission' required by West (1738-1820), and was excluded from his painting - and of course also from the print by William Woollett (1735-1785). Whether it was due to poverty (Hale had 21 children) or principle is uncertain. But here the arts of painting and printmaking, by deliberately manipulating facts (others are included who were not at Wolfe's side when he died), prove how unreliable they can be regarding historical truth.

Smallish creamware jugs may have been used for purposes other than serving beer - for example, for milk. The swelling barrel-shaped body with flaring foot and rim was one of the most popular jug forms in the last quarter of the 18th century.

Time

The taking of Quebec in 1759 by the British commander James Wolfe was the turning-point in a long-running struggle between the French and British for control of North America. The death of Wolfe at the moment of victory - like that of Nelson in 1805 at Trafalgar - caught the public imagination and turned him into a great hero. The engraving of Benjamin West's painting of 1771- The Death of General Wolfe - became the fastest-selling print of its time on publication in 1776. Yet retrospective representations of historical events are not always what they seem. When Wolfe was dying on the battlefield - the Heights of Abraham at Montreal - he asked his best friend, Colonel John Hale, to take home and present the despatches (the official report of the battle) to George II, who in turn asked Hale to raise a new regiment, the 17th Lancers. Later, Colonel Hale declined to pay the 100 guineas 'admission' required by West (1738-1820), and was excluded from his painting - and of course also from the print by William Woollett (1735-1785). Whether it was due to poverty (Hale had 21 children) or principle is uncertain. But here the arts of painting and printmaking, by deliberately manipulating facts (others are included who were not at Wolfe's side when he died), prove how unreliable they can be regarding historical truth.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Lead-glazed earthenware painted with crimson enamel and transfer-printed with purple |

| Brief description | Jug of lead-glazed earthenware painted with crimson enamel and transfer-printed, possibly made by Thomas Wolfe, possibly Staffordshire or Liverpool, ca. 1780. |

| Physical description | Jug of lead-glazed earthenware painted with crimson enamel and transfer-printed with purple. On one side is a ship in full sail, and on the other is the death of General Wolfe. Nearly barrel-shaped with a loop handle and projecting lip. Painted round the inside of the rim with a narrow crimson border. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Transferred from the Museum of Practical Geology, Jermyn Street |

| Object history | The death of General Wolfe is copied from the painting by Benjamin West. The jug was possibly made by Thomas Wolfe who claimed a relationship with the General. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Object Type Smallish creamware jugs may have been used for purposes other than serving beer - for example, for milk. The swelling barrel-shaped body with flaring foot and rim was one of the most popular jug forms in the last quarter of the 18th century. Time The taking of Quebec in 1759 by the British commander James Wolfe was the turning-point in a long-running struggle between the French and British for control of North America. The death of Wolfe at the moment of victory - like that of Nelson in 1805 at Trafalgar - caught the public imagination and turned him into a great hero. The engraving of Benjamin West's painting of 1771- The Death of General Wolfe - became the fastest-selling print of its time on publication in 1776. Yet retrospective representations of historical events are not always what they seem. When Wolfe was dying on the battlefield - the Heights of Abraham at Montreal - he asked his best friend, Colonel John Hale, to take home and present the despatches (the official report of the battle) to George II, who in turn asked Hale to raise a new regiment, the 17th Lancers. Later, Colonel Hale declined to pay the 100 guineas 'admission' required by West (1738-1820), and was excluded from his painting - and of course also from the print by William Woollett (1735-1785). Whether it was due to poverty (Hale had 21 children) or principle is uncertain. But here the arts of painting and printmaking, by deliberately manipulating facts (others are included who were not at Wolfe's side when he died), prove how unreliable they can be regarding historical truth. |

| Bibliographic reference | Hildyard, Robin. European Ceramics. London: V&A Publications, 1999.

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 3630-1901 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 4, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest