Milton Shield

Shield

1866 (made)

1866 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The Milton Shield is one of the most spectacular examples of highly-skilled metalworking in the V&A collection and during the 19th century, when it was made, was one of the most famous. It is the work of the brilliant French steel and silver worker, Léonard Morel-Ladeuil who made it for Elkington & Co. of Birmingham. The shield was made especially for the Paris Exhibition of 1867 where it won a gold medal for the artist and received an enormously enthusiastic response. The Art Journal declared, 'There is a general impression that the work ... is the best ... exhibited during the memorable year of 1867'. The Museum bought the shield from the exhibition for the then huge sum of £2,000.

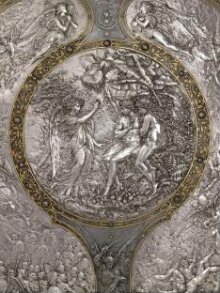

The theme of the shield was carefully chosen to celebrate the work of the poet John Milton (1608-74), whose epic work, 'Paradise Lost', had been published 200 years earlier. The central silver medallion shows the archangel Raphael admonishing Adam and Eve. Two more silver panels either side depict, on the left, loyal angels ascending to heaven, and, on the right, defeated rebel angels descending into hell, which gives the whole composition a sense of swirling, circular movement. The shield was made with the intention of producing copies. Electrotype reproductions were produced in huge numbers so that collectors, artists, designers and students all around the world could enjoy this great masterpiece simultaneously.

The theme of the shield was carefully chosen to celebrate the work of the poet John Milton (1608-74), whose epic work, 'Paradise Lost', had been published 200 years earlier. The central silver medallion shows the archangel Raphael admonishing Adam and Eve. Two more silver panels either side depict, on the left, loyal angels ascending to heaven, and, on the right, defeated rebel angels descending into hell, which gives the whole composition a sense of swirling, circular movement. The shield was made with the intention of producing copies. Electrotype reproductions were produced in huge numbers so that collectors, artists, designers and students all around the world could enjoy this great masterpiece simultaneously.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Milton Shield (manufacturer's title) |

| Materials and techniques | Damascened steel with inset plaques of silver |

| Brief description | Display shield of chased and damascened steel inset with chased silver plaques depicting scenes from John Milton's 'Paradise Lost', made by Léonard Morel-Ladeuil in London for Elkington & Co. of Birmingham, 1866, and shown at the Paris Exhibition of 1867. |

| Physical description | Damascened steel with inset chased silver plaques. Executed by Leonard Morel-Ladeuil for Elkington & Co. The illustration from Milton's Paradise Lost represent in the central Medallion the archangel Raphael recounting to Adam and Eve the defeat of the rebel angels Silver, embossed and oxidised, damascened iron |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | The Milton Shield is the best-known work of the brilliant French repoussé sculptor Léonard Morel-Ladeuil (c.1820-88) and is a tour-de-force of intricate steel and silver handcrafting techniques and gold inlay, skills inspired by the works of Renaissance armourers and goldsmiths. From 1859, Morel-Ladeuil worked for pioneering art-metal manufacturers, Elkington & Co. of Birmingham and London, sculpting painstaking shields, vases and salvers that were the company's showpieces at international exhibitions. The Milton Shield was created in 1866 for show at the Paris Exposition Universelle the following year. Henry Cole, first director of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), earmarked it for the museum collection before it set sail for France, and it joined the collection the following year after being toured around Britain. The theme of the shield was carefully chosen to celebrate the work of the poet, John Milton (1608-74). Its framework, a steel oval inset with silver bas-reliefs, depicts scenes from Milton's 'Paradise Lost', his great allegory of post-Civil War England, which had been published exactly 200 years earlier. The composition is unified by narrow 'arabesque' panels of inlaid ('damascened') gold. The central silver medallion shows the archangel Raphael admonishing Adam and Eve. It has an elasticity so undercut that the foliage appears to sprout from the surface. Two more silver panels either side depict, on the left, loyal angels ascending to heaven, and, on the right, defeated rebel angels descending into hell, which gives the whole composition a sense of swirling, circular movement. Morel-Ladeuil's genius lay in chasing and repoussé, the laborious, highly-skilled manipulation of steel and silver that involves heating and hammering metals into intricate shapes using fine steel punches of various sizes. In chasing, the metal is worked from the front by repeatedly tapping the surface. In repoussé, the metal is 'pushed' up from the back. Morel-Ladeuil had been a pupil in Paris of the great historicist and steel chaser Antoine Vechte (1799-1868) before coming to England to work for Elkington. By the time he produced the Milton Shield he was the greatest exponent of this work and had become internationally famous. Sculpting a soft metal like silver requires extremely high skill levels; manipulating hard steel, the way Morel-Ladeuil did on the Milton Shield requires breathtaking artistry. The astonishingly subtle manipulation of steel in the sinuous figure of St. Michael vanquishing the dragon and the delicate, transparent veil covering the Grim Reaper's face are bravura displays of Morel-Ladeuil's brilliance. The shield caused a sensation in Paris. The 'Art Journal' in 1868 illustrated it and declared, 'There is a general impression that the work here engraved is the best work exhibited during the memorable year of 1867.' 'The Times' on 4 September 1867 noted there was 'always a crowd of admirers around it. The work in it is of the finest quality, and the ideas which are expressed in that work are not only full of poetry, but sometimes also reach even to the sublime.' George Wallis, First Keeper of Fine Art at the V&A, was beside himself with admiration: 'Every face expresses the appropriate mental emotion or passion. There is awe and fear expressed in the face of Adam, and modesty in that of Eve, as they listen to the recital by Raphael of the conflict between the hosts of Heaven and Hell ... There is Michael-Angelo-like force of drawing in the terrified faces and forms of the defeated rebels ... How fiercely St. Michael wields his flaming sword, as he stands on the prostrate body of the Dragon!' On its return from Paris, the Shield toured Elkington's regional showrooms. In January 1868 the Liverpool Mercury declared it 'one of the grandest works of its class that has been produced in any age or country.' Cole persuaded the government to part with £2,000 to secure it for the nation. It was the second most expensive contemporary artwork bought by the Museum before 1900. |

| Historical context | Morel-Ladeuil, working for Elkington, won gold medals at every world fair from 1862 to 1878. His fame during the 1860s turned his London studio into a visitor attraction. 'Around this time the company opened in the capital, amid the opulence of Regent Street, a magnificent new showroom. Above it was a vast and light workshop. It was there, over the next twenty-three years, that the artist produced a series of chased repoussé artworks, which excel, at least in quantity and importance, the work of any famous goldsmith. Always easy, accessible, and courteous, it was in this workshop that he cheerfully received the many visitors who climbed their steps: London's artists and critics, French visitors, and fashionable society figures from around the world, all desirous of meeting the artist and witnessing the creative processes behind these artworks, which at each new [International] Exhibition found such radiant acclaim.' The shield was made with replication in mind. Large industrial art manufacturers like Elkington broadcast their reputations internationally by showing virtuoso creations that revived historic handcrafting techniques. Simultaneously, they expedited those processes through scientific and mechanical means, creating replicas in less expensive materials for a wider market. Elkington replicated the shield in copper using electroforming, electroplating and electrogilding techniques (electrotypes). The company had invested heavily in developing, patenting and licensing such techniques to other manufacturers. On buying the Milton Shield, the museum commissioned four electrotype copies of it for use in the art schools, either at South Kensington or for circulation around the country. An additional copy, dating from 1886 and mounted to a hinged easel, shows how the shield was intended to be seen, close-up at eye level. The Museum advertised electrotypes of the shield for sale in 1873. The highest quality copies of 'this noble work of art' were priced in the catalogue at 12 guineas each. Cheaper versions were also sold in plain electroplate and bronzed (copper sulphate) finishes. In all hundreds of electrotypes of the shield were made. They were such accurate copies that they enabled a key artwork like the Milton Shield to be enjoyed, admired and studied around the word simultaneously. Examples in a variety of finishes, entered international collections. Buyers included major museums in Boston, New York, Paris, Vienna and Sydney, as well as the White House in Washington, D.C. Private collectors and wealthy industrialists bought copies to furnish their homes. The popularity of the shield was also longlasting. An electrotype of it was shown at the Weltausstellung, Vienna's World Fair, of 1873. It attracted universal approval once again when an electrotype adorned Elkington's stand at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. For post-Civil War America, the shield resonated powerfully with fresh memories of political strife and social upheaval. Although Morel-Ladeuil had created an extraordinarily beautiful new piece for the exhibition 'The Pompeian Lady Plaque', sales of electrotypes of the Milton Shield, by now 10 years old, kept pace with copies of the plaque. Indeed, such was the longevity of the shield's popularity that Elkington was still advertising copies in the company's sale catalogues of 1904, and exhibiting it in its showrooms in Birmingham, London, Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow. Always adept at publicizing its success, it claimed that given its purchase by 'the Government for the South Kensington Museum [it] has thus been adopted as a National Work of Art.' Given its fame in the 19th century it is surprising that the shield's creator's name is so little-known today. Morel-Ladeuil died in 1888 and by the time a catalogue of his works was created in 1904 by his nephew, Leon Morel ('L'Oeuvre de Morel-Ladeuil: Sculpteur-Ciseleur, 1820-1888'), his fame had receded dramatically. The march of modernism, especially after World War One, made his highly-ornamented works seem old-fashioned and although Elkington's multinational success had promoted his celebrity, it also heralded a new age of multinational luxury brands in which corporate identity increasingly subsumed individual creative talent. His catalogue of only forty-two known artworks is relatively prolific for a repoussé sculptor and reveals both how laborious his specialism was and the uncompromising level of excellence he sustained. The Milton Shield is his greatest work and one of the best examples of metalworking in the V&A collection. |

| Literary reference | Paradise Lost |

| Summary | The Milton Shield is one of the most spectacular examples of highly-skilled metalworking in the V&A collection and during the 19th century, when it was made, was one of the most famous. It is the work of the brilliant French steel and silver worker, Léonard Morel-Ladeuil who made it for Elkington & Co. of Birmingham. The shield was made especially for the Paris Exhibition of 1867 where it won a gold medal for the artist and received an enormously enthusiastic response. The Art Journal declared, 'There is a general impression that the work ... is the best ... exhibited during the memorable year of 1867'. The Museum bought the shield from the exhibition for the then huge sum of £2,000. The theme of the shield was carefully chosen to celebrate the work of the poet John Milton (1608-74), whose epic work, 'Paradise Lost', had been published 200 years earlier. The central silver medallion shows the archangel Raphael admonishing Adam and Eve. Two more silver panels either side depict, on the left, loyal angels ascending to heaven, and, on the right, defeated rebel angels descending into hell, which gives the whole composition a sense of swirling, circular movement. The shield was made with the intention of producing copies. Electrotype reproductions were produced in huge numbers so that collectors, artists, designers and students all around the world could enjoy this great masterpiece simultaneously. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 546-1868 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 29, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest