Narcissus

Statue

ca. 1560 (restored)

ca. 1560 (restored)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

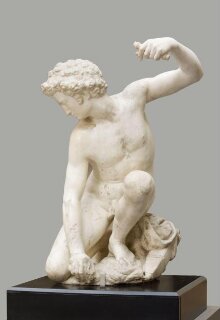

Narcissus is shown as a youth returning from a hunt. He stops to look into a pool of water and is mesmerised by his reflection, which he has never seen before. He falls in love with the beautiful image he sees and then cannot stop looking. This may have originally been the centrepiece for a fountain, and therefore shown the figure gazing into an actual pool of water.

When discovered in Florence this statue was identified as a statue of Cupid carved by Michelangelo which was thought to be lost. For many years after its acquisition by the V&A it was one of the most celebrated works in the Museum because of this attribution. It has since been identified as an ancient Roman copy of a classical model. It was extensively recut in the sixteenth century, with the head being added at this time, and is thought to be the work of the Florentine sculptor Valerio Cioli (ca. 1529 - 1599), who was a restorer of classical sculptures. The raised left arm dates from the nineteenth century.

When discovered in Florence this statue was identified as a statue of Cupid carved by Michelangelo which was thought to be lost. For many years after its acquisition by the V&A it was one of the most celebrated works in the Museum because of this attribution. It has since been identified as an ancient Roman copy of a classical model. It was extensively recut in the sixteenth century, with the head being added at this time, and is thought to be the work of the Florentine sculptor Valerio Cioli (ca. 1529 - 1599), who was a restorer of classical sculptures. The raised left arm dates from the nineteenth century.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Narcissus (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Carved marble with plaster additions |

| Brief description | Statue, marble with plaster repairs, Narcissus, Roman, probably recut by Valerio Cioli, Italy, ca.1564 |

| Physical description | The figure is shown half crouching on the draped stump of a tree, with the right knee on the ground and the left knee raised. The right hand, holding an indeterminate object, rests on the rocky base and the left arm is raised. Next to the tree stump is an empty quiver pierced to hold arrows. The body is twisted upwards to the left and the head looks down over the right shoulder. The raised left arm is a nineteenth-century restoration by Cavaliere Santarelli. An addition made at the same time by Saritarelli to the lower part of the rocky base has now been removed. The knuckles of the right band are repaired in plaster. There is a wedge-shaped area of plaster on the upper part of the left shoulder, and a corresponding area of plaster on the head. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | This piece was acquired in 1861 along with eighty-three other works from the combined collection of Ottavio Gigli and Marchese Giovan Pietro Campana. This collection led to the V&A’s sculpture collection becoming known as one of the most important features of the Museum. Subsequent research has shown that the collection is one of uneven quality and unreliable attributions, with this object having one of the most important re-appraisals. Maclagan and Longhurst (1932) summarise the history of the attribution to Michelangelo, first made in the mid-nineteenth century by Migliarini and the sculptor Santarelli (who also restored the raised left arm), who noted that the head is a replacement. Santarelli and Migliarini also said that the knuckles on the right hand had been repaired with stucco, and the object had been damaged by bullets. It had apparently been found either in the cellar in the Orti Oricellari or the Gualfonda gardens, both in Florence. It was sold by the Marchese Giuseppe Stiozzi to Gigli in 1854. Many subsequent researchers agreed with the assertion that it was the lost Cupid by Michelangelo made for Jacopo Galli. Some art historians rejected the identification of the piece as the Galli Cupid, but maintained the attribution to Michelangelo, while others have contested both assertions. John Pope-Hennessy’s technical examination (1956 and 1964) of the figure is the one adhered to here. The body has been extensively re-cut: the right upper forearm, shoulder and breast, the neck, the left side of the torso, outer side of left thigh and the right ankle. The areas which have not been re-cut have deteriorated and are pitted with small indentations. This is consistent with weathering and has parallels with the deterioration of classical sculpture. The head and the body are made from two different types of marble. The carving of the throat suggests that the head originally turned sharply to the left. Pope-Hennessy wrote that the figure had been transferred from the Gualfonda gardens to the Orti Oricellari, then bought by Gigli. He concluded that it is a Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, that the head was added in the sixteenth century, and the whole was extensively re-cut in the nineteenth century. In some classical literature Narcissus is described as a youth returning from a hunt, which would explain the quiver of arrows at his feet, and suggests that there would originally have been a bow (which may also explain the raised left arm). The figure would most likely have been placed at the centre of a fountain, which explains the angle of the head. The hair and features show points of resemblance with the work of Valerio Cioli (ca. 1529 – 1599), a Florentine sculptor. Historical significance: Valerio Cioli is mentioned by Vasari in his Lives of the Most eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, as ‘Valerio Cioli of Settignano, a sculptor and Academician’, however he is not allotted a biography of his own. Also mentioned is his son Simone. Cioli worked with Michelangelo for the Vatican. He was commissioned to produce work for Michelangelo’s tomb after he died, one of three sculptures representing Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Vasari also writes that Cioli is known to have restored antique sculptures, doing so for the garden of the Cardinal of Ferrara in Rome and for the Pitti Palace in Florence, ‘making for some of them new arms, for some new feet and for others other parts that were wanting’. He seems to have carried out many carvings of figures intended for fountains, which supports the assertion that this figure is a Narcissus intended to sit atop a pool of water. The re-working of Roman sculptures unearthed in excavations, as is evidenced in what Vasari wrote about Cioli, was a common occurrence at this time, with archaeological excavations uncovering architecture, paintings and sculpture. |

| Historical context | According to classical mythology Narcissus, the son of Cephisus (the Boeotian river) and Liriope, a nymph, fell in love with no one until he saw his own reflection in a pool of water and feel in love with it. He eventually died and was turned into the flower that now bears his name. Another myth tells of Echo, who was condemned to repeat only the last words that had been spoken to her, she fell in love with Narcissus but was rejected by him. His punishment for this was to fall in love with his own reflection and die gazing and pining after his reflection. The ancient world believed that the soul was contained in a person’s reflection, and to dream of it was a premonition of death. For the Greeks the narcissus flower came to represent youthful death. Narcissus, therefore, was an ideal subject for the central sculpture of a fountain. |

| Production | Mainly a Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, with restorations and additions made by Valerio Cioli |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Narcissus is shown as a youth returning from a hunt. He stops to look into a pool of water and is mesmerised by his reflection, which he has never seen before. He falls in love with the beautiful image he sees and then cannot stop looking. This may have originally been the centrepiece for a fountain, and therefore shown the figure gazing into an actual pool of water. When discovered in Florence this statue was identified as a statue of Cupid carved by Michelangelo which was thought to be lost. For many years after its acquisition by the V&A it was one of the most celebrated works in the Museum because of this attribution. It has since been identified as an ancient Roman copy of a classical model. It was extensively recut in the sixteenth century, with the head being added at this time, and is thought to be the work of the Florentine sculptor Valerio Cioli (ca. 1529 - 1599), who was a restorer of classical sculptures. The raised left arm dates from the nineteenth century. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 7560-1861 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 20, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest