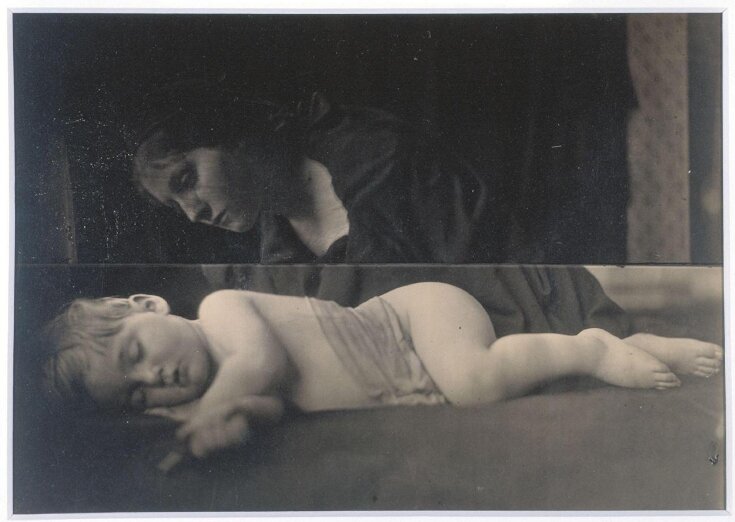

My Grand Child Archie Son of Eugene Cameron R.A. aged 2 years & 3 months

Photograph

1865 (photographed)

1865 (photographed)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Julia Margaret Cameron accepted and even embraced irregularities that other photographers would have rejected as technical flaws. In addition to her pioneering use of soft focus, she scratched into her negatives, printed from broken or damaged ones and occasionally used multiple negatives to form a single picture. Although criticised at the time as evidence of ‘slovenly’ technique, these traces of the artist’s hand in Cameron’s prints can now be appreciated for their modernity.

Cameron was not uncritical of her work and strove to improve her skills. She sought the opinion of her mentor, the painter G. F. Watts, though at his insistence she sent him imperfect prints for comment, reserving the more successful ones for potential sale. Cameron also sought advice from the Photographic Society and from Henry Cole, the founding director of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) on combatting the ‘cruel calamity’ of crackling that had ruined some of her ‘most precious negatives’.

Cameron printed the bottom half of a negative of her sleeping grandson both on its own and in combination with the top half of a negative of Mary Hillier. ‘Combination printing’, or forming a single print from multiple negatives, was practiced more subtly by other Victorian photographers, often to overcome the problem of photographing multiple sitters at once.

Cameron was not uncritical of her work and strove to improve her skills. She sought the opinion of her mentor, the painter G. F. Watts, though at his insistence she sent him imperfect prints for comment, reserving the more successful ones for potential sale. Cameron also sought advice from the Photographic Society and from Henry Cole, the founding director of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) on combatting the ‘cruel calamity’ of crackling that had ruined some of her ‘most precious negatives’.

Cameron printed the bottom half of a negative of her sleeping grandson both on its own and in combination with the top half of a negative of Mary Hillier. ‘Combination printing’, or forming a single print from multiple negatives, was practiced more subtly by other Victorian photographers, often to overcome the problem of photographing multiple sitters at once.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | My Grand Child Archie Son of Eugene Cameron R.A. aged 2 years & 3 months (assigned by artist) |

| Materials and techniques | Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative |

| Brief description | Photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, 'My Grand Child Archie Son of Eugene Cameron R.A. aged 2 years & 3 months' (sitters Archibald Cameron, Mary Hillier), albumen print, 1865 |

| Physical description | Photograph of a sleeping child (Archibald Cameron) positioned on his side with a cloth draped over his mid-section overlooked by a woman (May Hillier) leaning in towards him. The image is made from two negatives |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | 'My Grandchild Archie, son of Eugene Cameron, aged two years and three month / Julia Margaret Cameron' (ink) |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Given by or Purchased from Julia Margaret Cameron, 27 September 1865 |

| Object history | Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–79) was one of the most important and innovative photographers of the 19th century. Her photographs were rule-breaking: purposely out of focus, and often including scratches, smudges and other traces of the artist’s process. Best known for her powerful portraits, she also posed her sitters – friends, family and servants – as characters from biblical, historical or allegorical stories. Born in Calcutta on 11 June 1815, the fourth of seven sisters, her father was an East India Company official and her mother descended from French aristocracy. Educated mainly in France, Cameron returned to India in 1834. In 1842, the British astronomer Sir John Herschel (1792 – 1871) introduced Cameron to photography, sending her examples of the new invention. They had met in 1836 while Cameron was convalescing from an illness in the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. He remained a life-long friend and correspondent on technical photographic matters. That same year she met Charles Hay Cameron (1795–1880), 20 years her senior, a reformer of Indian law and education. They married in Calcutta in 1838 and she became a prominent hostess in colonial society. A decade later, the Camerons moved to England. By then they had four children; two more were born in England. Several of Cameron’s sisters were already living there, and had established literary, artistic and social connections. The Camerons eventually settled in Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight. At the age of 48 Cameron received a camera as a gift from her daughter and son-in-law. It was accompanied by the words, ‘It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater.’ Cameron had compiled albums and even printed photographs before, but her work as a photographer now began in earnest. The Camerons lived at Freshwater until 1875, when they moved to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) where Charles Cameron had purchased coffee and rubber plantations, managed under difficult agricultural and financial conditions by three of their sons. Cameron continued her photographic practice at her new home yet her output decreased significantly and only a small body of photographs from this time remains. After moving to Ceylon the Camerons made only one more visit to England in May 1878. Julia Margaret Cameron died after a brief illness in Ceylon in 1879. Cameron’s relationship with the Victoria and Albert Museum dates to the earliest years of her photographic career. The first museum exhibition of Cameron's work was held in 1865 at the South Kensington Museum, London (now the V&A). The South Kensington Museum was not only the sole museum to exhibit Cameron’s work in her lifetime, but also the institution that collected her photographs most extensively in her day. In 1868 the Museum gave Cameron the use of two rooms as a portrait studio, perhaps qualifying her as its first artist-in-residence. Today the V&A’s Cameron collection includes photographs acquired directly from the artist, others collected later from various sources, and five letters from Cameron to Sir Henry Cole (1808–82), the Museum’s founding director and an early supporter of photography. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Julia Margaret Cameron accepted and even embraced irregularities that other photographers would have rejected as technical flaws. In addition to her pioneering use of soft focus, she scratched into her negatives, printed from broken or damaged ones and occasionally used multiple negatives to form a single picture. Although criticised at the time as evidence of ‘slovenly’ technique, these traces of the artist’s hand in Cameron’s prints can now be appreciated for their modernity. Cameron was not uncritical of her work and strove to improve her skills. She sought the opinion of her mentor, the painter G. F. Watts, though at his insistence she sent him imperfect prints for comment, reserving the more successful ones for potential sale. Cameron also sought advice from the Photographic Society and from Henry Cole, the founding director of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) on combatting the ‘cruel calamity’ of crackling that had ruined some of her ‘most precious negatives’. Cameron printed the bottom half of a negative of her sleeping grandson both on its own and in combination with the top half of a negative of Mary Hillier. ‘Combination printing’, or forming a single print from multiple negatives, was practiced more subtly by other Victorian photographers, often to overcome the problem of photographing multiple sitters at once. |

| Associated object | 45:162 (Version) |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 45159 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 11, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest