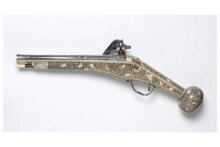

Wheel Lock Pistol

1579 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Arms and armour are rarely associated with art. However, they were influenced by the same design sources as other art forms including architecture, sculpture, goldsmiths' work, stained glass and ceramics. These sources had to be adapted to awkward shaped devices required to perform complicated technical functions. Armour and weapons were collected as works of art as much as military tools.

This wheel-lock pistol has a mechanism that enabled it to be carried loaded. The jaws of the lock clamped a piece of flint or a piece or pyrites designed to rub against the rough edge of the wheel projecting into the pan. The wheel was revolved at speed by a tightly coiled spring, wound by a separate spanner, and released when the gun's trigger was pulled causing sparks to ignite the gunpowder in the breech.

Sketches for wheel-locks were made by Leonardo da Vinci but their first common use was in Germany in around 1520 and they continued in use until the late seventeenth century. They were the first devices to fire guns mechanically and accelerated the development of firearms by negating the need for long and dangerous 'match' cords which had to be kept dry. The increasingly powerful gunpowder of the mid-16th century encouraged the development of smaller guns including the pistol, and many were fitted with wheel locks. A loaded pistol could be concealed under a cloak, to the concern of European rulers. Elizabeth I forbade anyone from carrying a mechanical firearm within 500 yards of a royal palace and in 1584 William the Silent was the first monarch to be assassinated with a wheel lock gun.

As technical devices wheel-locks attracted princely collectors. Many are finely chiselled and engraved as works of art, some even on their insides, to be taken apart and reassembled at pleasure. The stocks were also often decorated with fine bone and horn inlays drawing on the skills of furniture makers and engravers. Wheel-lock guns were expensive, however, and most ordinary gunners were equipped with the older style match-locks until well into the seventeenth century.

This wheel-lock pistol has a mechanism that enabled it to be carried loaded. The jaws of the lock clamped a piece of flint or a piece or pyrites designed to rub against the rough edge of the wheel projecting into the pan. The wheel was revolved at speed by a tightly coiled spring, wound by a separate spanner, and released when the gun's trigger was pulled causing sparks to ignite the gunpowder in the breech.

Sketches for wheel-locks were made by Leonardo da Vinci but their first common use was in Germany in around 1520 and they continued in use until the late seventeenth century. They were the first devices to fire guns mechanically and accelerated the development of firearms by negating the need for long and dangerous 'match' cords which had to be kept dry. The increasingly powerful gunpowder of the mid-16th century encouraged the development of smaller guns including the pistol, and many were fitted with wheel locks. A loaded pistol could be concealed under a cloak, to the concern of European rulers. Elizabeth I forbade anyone from carrying a mechanical firearm within 500 yards of a royal palace and in 1584 William the Silent was the first monarch to be assassinated with a wheel lock gun.

As technical devices wheel-locks attracted princely collectors. Many are finely chiselled and engraved as works of art, some even on their insides, to be taken apart and reassembled at pleasure. The stocks were also often decorated with fine bone and horn inlays drawing on the skills of furniture makers and engravers. Wheel-lock guns were expensive, however, and most ordinary gunners were equipped with the older style match-locks until well into the seventeenth century.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Steel, chiselled and engraved, with walnut stock engraved and inlaid with staghorn |

| Brief description | Wheel lock pistol inlaid with engraved staghorn, South German, dated 1579. |

| Physical description | The stock is inlaid with closely set spiral foliate scrolls of staghorn enclosing grotesque masks, birds and monkeys in engraved staghorn. The stock bears the maker's signature, the initials H B and the date (15)79. The butt is of the large ball type. The lock, with exterior safety catch, is unmarked. The barrel is lightly chiselled with grotesque masks and foliage. It bears the barrel-smith's initials and also his mark of a chamois' head between S and R with the figures 73 in a shaped shield. The figure should probably be read as 1573, and perhaps record the date of registration of the mark. On the barrel the date 1579. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Object history | Historical significance: A companion pistol is in the Musée de l'Armée in Paris. Two powder flasks in the V&A are decorated en suite with this pistol, which belongs to a large group of similarly decorated pieces. There are numbers in the Dresden Rüstkammer and they are sometimes described as Saxon, conforming to the South German fashion of the period 1575-1599. |

| Historical context | Arms and armour are rarely associated with art. However, they were influenced by the same design sources as other art forms including architecture, sculpture, goldsmiths' work, stained glass and ceramics. These sources had to be adapted to awkward shaped devices required to perform complicated technical functions. Armour and weapons were collected as works of art as much as military tools. This wheel-lock pistol has a mechanism that enabled it to be carried loaded. The jaws of the lock clamped a piece of flint or a piece or pyrites designed to rub against the rough edge of the wheel projecting into the pan. The wheel was revolved at speed by a tightly coiled spring, wound by a separate spanner, and released when the gun's trigger was pulled causing sparks to ignite the gunpowder in the breech. Sketches for wheel-locks were made by Leonardo da Vinci but their first common use was in Germany in around 1520 and they continued in use until the late seventeenth century. They were the first devices to fire guns mechanically and accelerated the development of firearms by negating the need for long and dangerous 'match' cords which had to be kept dry. The increasingly powerful gunpowder of the mid-16th century encouraged the development of smaller guns including the pistol, and many were fitted with wheel locks. A loaded pistol could be concealed under a cloak, to the concern of European rulers. Elizabeth I forbade anyone from carrying a mechanical firearm within 500 yards of a royal palace and in 1584 William the Silent was the first monarch to be assassinated with a wheel lock gun. As technical devices wheel-locks attracted princely collectors. Many are finely chiselled and engraved as works of art, some even on their insides, to be taken apart and reassembled at pleasure. The stocks were also often decorated with fine bone and horn inlays drawing on the skills of furniture makers and engravers. Wheel-lock guns were expensive, however, and most ordinary gunners were equipped with the older style match-locks until well into the seventeenth century. |

| Summary | Arms and armour are rarely associated with art. However, they were influenced by the same design sources as other art forms including architecture, sculpture, goldsmiths' work, stained glass and ceramics. These sources had to be adapted to awkward shaped devices required to perform complicated technical functions. Armour and weapons were collected as works of art as much as military tools. This wheel-lock pistol has a mechanism that enabled it to be carried loaded. The jaws of the lock clamped a piece of flint or a piece or pyrites designed to rub against the rough edge of the wheel projecting into the pan. The wheel was revolved at speed by a tightly coiled spring, wound by a separate spanner, and released when the gun's trigger was pulled causing sparks to ignite the gunpowder in the breech. Sketches for wheel-locks were made by Leonardo da Vinci but their first common use was in Germany in around 1520 and they continued in use until the late seventeenth century. They were the first devices to fire guns mechanically and accelerated the development of firearms by negating the need for long and dangerous 'match' cords which had to be kept dry. The increasingly powerful gunpowder of the mid-16th century encouraged the development of smaller guns including the pistol, and many were fitted with wheel locks. A loaded pistol could be concealed under a cloak, to the concern of European rulers. Elizabeth I forbade anyone from carrying a mechanical firearm within 500 yards of a royal palace and in 1584 William the Silent was the first monarch to be assassinated with a wheel lock gun. As technical devices wheel-locks attracted princely collectors. Many are finely chiselled and engraved as works of art, some even on their insides, to be taken apart and reassembled at pleasure. The stocks were also often decorated with fine bone and horn inlays drawing on the skills of furniture makers and engravers. Wheel-lock guns were expensive, however, and most ordinary gunners were equipped with the older style match-locks until well into the seventeenth century. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 612-1893 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 5, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest