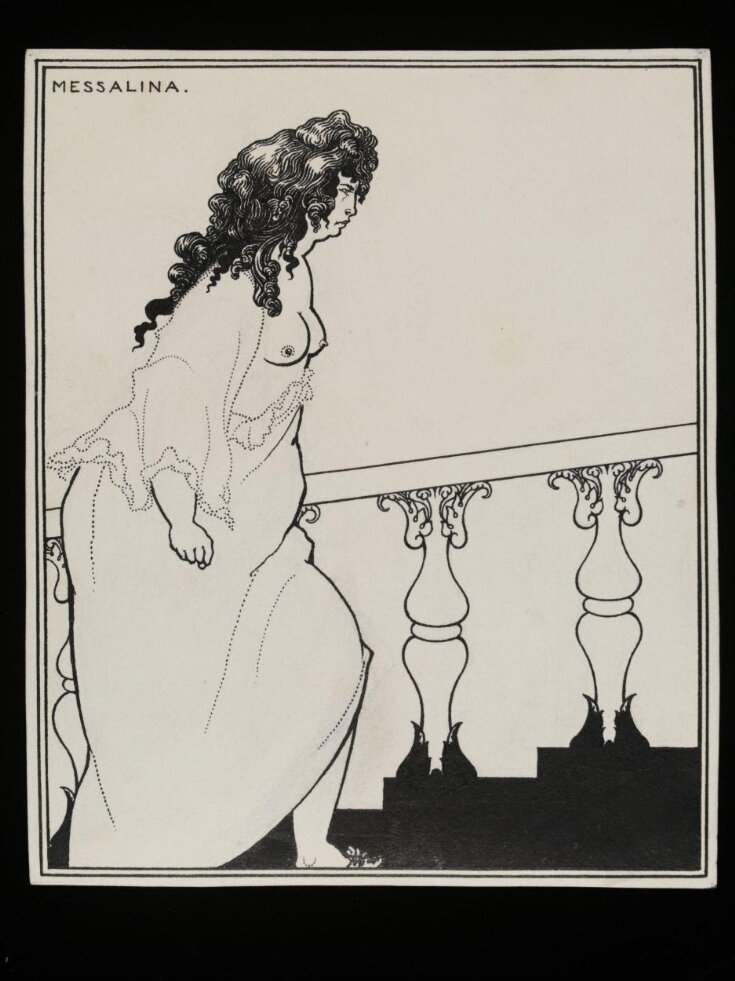

Messalina returning home

Drawing

1896 (made)

1896 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Drawing of a woman dressed in a loose gown, her breasts exposed, climbing a baroque staircase.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Messalina returning home (published title) |

| Materials and techniques | Pen and ink on paper |

| Brief description | Drawing by Aubrey Beardsley, ‘Messalina returning home’, illustration to the Sixth Satire of Juvenal, published by Leonard Smithers in An Issue of Five Drawings Illustrative of Juvenal and Lucian, London, 1906 |

| Physical description | Drawing of a woman dressed in a loose gown, her breasts exposed, climbing a baroque staircase. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | MESSALINA |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Purchased with Art Fund support |

| Object history | Provenance: William King; Mrs Viva King; R. A. Harari |

| Literary reference | Sixth Satire of Juvenal , published by Leonard Smithers in An Issue of Five Drawings Illustrative of Juvenal and Lucian , London, 1906 |

| Associated object | E.684-1945 (Reproduction) |

| Bibliographic reference | Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley : a catalogue raisonne. New Haven : Yale University Press, [2016] 2 volumes (xxxi, [1], 519, [1] pages; xi, [1], 547, [1] pages) : illustrations (some color) ; 31 cm. ISBN: 9780300111279

The entry is as follows:

1060

Messalina

By 25 August 1896

Victoria and Albert Museum, London (E.302-1972)

Pen, Indian ink, brush over pencil underdrawing on white wove paper laid down; 7 x 5 3/4 inches (178 x 146 mm).

INSCRIPTIONS: Recto in ink inscribed by artist at upper left corner: MESSALINA

FLOWERS: Rose [Bourbon type] (love, passion); olive branch (peace); chrysanthemum [on slop jar] (truth, love, slighted love).

PROVENANCE: Leonard Smithers; …; bt. William King (Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities, British Museum) c.1919-20 (PUL-ABC, Box 5, folder 13, als to A. E. Gallatin, 3 August 1944); bequeathed to Mrs Viva King; Sotheby’s (London) sale 17-19 February 1930 (389); bt. Savile Gallery; bt. Frank Hollings (bookseller); Cecil French (in 1936);... bt. R. A. Harari (by 1958), by descent to Michael Harari; bt. Victoria and Albert Museum in 1972 with the aid of a contribution from the National Art Collections Fund.

EXHIBITION: London 1910a (168, ?’Lucretia Borgia’), 1923-4 (51); 1966-8 (472); Tokyo 1983 (109); Munich 1984 (245); Rome 1985 (8.3); London 1993 (116); Kanagawa, Japan 1998 (170).

LITERATURE: Vallance 1897 (p.210, where titled ‘Messalina returning home’); ‘Saturday Review’ 30 September 1899 (p. 419); Blei 1899/1900 (p. 259); Vallance 1909 (no. 159, where titled ‘Messalina returning home from the Bath’, but medium incorrectly listed as ‘pen-and-ink and watercolours’, and thus confused with ‘Messalina’ (no. 948 above); National Gallery, London 1923-4 (no. 51); Gallatin 1945 (no. 972); Blunt and Poole 1962 (p. 9); Reade 1967 (p. 363, n. 483); ‘Letters’ 1970 (pp. 79, 150, 151-5, 185); Brophy 1976a (p. 41); Clark 1979 (p. 134); Wilson 1983 (plate 40); Fletcher 1987 (p. 176) Zatlin 1990 (p. 57); Samuels Lasner 1995 (no.149a); Stokes 1996 (pp. 119-22); Zatlin 1997 (pp. 34-5, 123); Wilson 2002; Stokes 2005 (p. 117).

REPRODUCED: ‘An Issue of Five Drawings Illustrative of Juvenal and Lucian’, published by Leonard Smithers in 1898 [i.e. 1906]; ‘Second Book of Fifty Drawings’ 1899 (plate 45); ‘Later Work’ 1901 (no. 157); ‘Best of Beardsley’ 1948 (plate 120); Reade 1967 (plate.483); Clark 1979 (plate 58); Wilson 1983 (plate 40).

This drawing is also known as ‘Messalina returning from the Bath’. The second of two drawings Beardsley made of the notorious Roman empress Messalina, illustrating references to her in the Latin poet Juvenal’s ‘Sixth Satire’. The earlier drawing (no. 948 above) shows Messalina wearing a blonde wig for disguise as she sallies forth on one of her nightly visits to the brothel. The one under discussion here details her return home. When Beardsley completed this drawing on 25 August 1896, he announced to his publisher Leonard Smithers that it could go into his ‘Book of Fifty Drawings’, which he called his ‘album’, then in the preparatory stages: ‘The Messalina’, he wrote, ‘which I have just finished for the VIth [i.e. the ‘Sixth Satire’ of Juvenal] will do quite well for the Album’ (‘Letters’ 1970, p. 155). There is no further mention of this piece until 17 October 1896, when he questioned Smithers about placing the drawing into the last issue of the ‘Savoy’: ‘Messalina is going in the 8th Savoy I presume?’ (p. 185). Instead, Smithers held it, publishing it posthumously first in 1899 and then in 1906 with the other drawings for Juvena; in an edition of supposedly only twenty copies.

Beardsley owned and marked a copy of Dryden’s 1697 version of Juvenal (now at Princeton University Library), and later admired Barten Holyday’s 1673 translation (p. 154 [postmarked 21 August 1896]). In December 1894, from St Mary’s Abbey, Windermere, where he was on holiday, however, he was interested in Gifford’s translation and requested from Elkin Mathews ‘one copy of the first or some early edition’ (p. 79). He also owned the Bohn’s Classical Library edition (1852) and asked Smithers to send him the translation by the Rev. Madan (p. 151). He himself read Latin and says on 11 August, ‘I am making the translation as well as the pictures’ (p. 150), and most probably based his drawings on an amalgam of the translations he had read and his own knowledge of the original text. The part of the Messalina passage that Beardsley marked in his Dryden translation is the following, and the final six lines relate specifically to this drawing:

To the known Brothel-house she takes her way;

And for a masty Room gives double pay;

That room in which the rankest Harlot lay.

At length when friendly darkness is expir’d,

And ev’ry strumpet from her cell retir’d,

She lags behind, and ling’ring at the gate,

With a repining sign submits to fate:

All filth without, and all a fire within

Tir’d with the toil, unsated with the sin.

Oh! Caesar’s bed the modest matron seeks;

The steam of lamps still hanging on her cheeks,

In ropy smut: thus foul and thus bedight,

She brings him back the product of the night (p. 241)

Dryden’s translation was extremely free and the underlying facts and Beardsley’s response to them may be illuminated by a modern translation:

… she would make straight for her brothel,

With its odour of stale, warm bedclothes, its empty reserved cell.

Here she would strip off, showing her gilded nipples and

The belly that once housed a prince of the blood. Her door sign

Bore a false name, Lycisca, the ‘Wolf-girl’. A more than willing

Partner, she took on all comers, for cash, without a break.

Too soon for her the brothel keeper dismissed

His girls. She stayed to the end, always the last to go,

Then trailed away sadly, still with a burning hard on,

Retiring exhausted, yet still far from satisfied, cheeks

Begrimed with lamp-smoke; filthy, carrying home

To her imperial couch the stink of the whorehouse (Peter Green, Penguin Classics, 1967)

In the evocation of Messalina , Wilson says, ‘Beardsley has brilliantly imaged her return, trailing up the palace stairs, clothes and hair dishevelled, her clothes indeed reduced to a mere shift, nipples still erect, grim-faced and, the final nice touch, fist clenched in frustration (Wilson 2002). Juvenal’s text makes it clear that the word bath in the title ‘Messalina returning from the bath’, which has erratically been attached to both this and the earlier drawing, is a euphemism for bagnio (brothel). Leonard Smithers, in his ‘Catalogue of Rare Books 3’ had described the earlier drawing, confusing its subject, as ‘Messalina returning from the Lupanar’, another word for brothel (no. 948 above). Those titles are clearly accurate for this drawing.

As a subject, Messalina has a specific reference for the 1890s when prostitution and the New Woman’s claim for sexual freedom made headlines; as Stokes argues, ‘these meanings could be further played off against each other to suggest either the complicated causes of sexual exploitation, or to provide ancient evidence of rapacious female desire’ (1996. P. 120). When the drawing was first published in 1899, writers could not openly focus on either issue; consequently, they scrutinised Beardsley’s treatment and slightly dismissed its power. For example, D. S. MacColl, who had known Beardsley, wrote ‘This voluptuous person, exhibiting her charms with the angry decent pomp of a dowager, is one of Beardsley’s funniest whims’ (‘Saturday Review’ 30 September 1899, p. 419). In Germany, Franz Blei, who usually praised Beardsley’s work, found little to appreciate in this Messalina, ‘a woman over fifty’, whose ‘figure is gone’ and who has ‘staring eyes and fat lips’ (1899/1900, p. 259; translation, Katharina Licht). Later critics discern that her expression is more powerful that Beardsley’s early Messalina, and her movement more natural. Reade says Beardsley shows her ‘gross power [in] stouter and heavier lines’ than any since the cover of the ‘Yellow Book’, vol i (Reade 1967, p. 363, n.483). Walker asserts that this drawing is the final evolution of the style ‘when he drew black on white merely delineating form by the thickness or delicacy of the line. … [Here] he uses the black stairs as a base, but in the best drawings of this period he is able to dispense with any base, ground or background. The only influence is pure Greek art of the best period. In fact, in 1896, he carried the pen and ink drawing to the highest point it had ever reached as the medium for a work of art. Realising this himself, he turned to the brush and pencil during the last few months of his life (1823-4, no. 51).

Later critics discuss Messalina according to their gender. Fletcher believes that Beardsley isolates her figure in order to concentrate on ‘the savage nature of Messalina’s fiery pursuit of sexual pleasure. She is perhaps the most accomplished example of Beardsley’s version of the nineteenth-century femme fatale, with her malignant breasts suggesting opposition to the fructifying powers of woman, viewed now as emblems of decay [as Beardsley who both] fears and is attracted to what he excoriates’, responds closely to the Latin text and satirises Messalina (1987, p. 176). Clark confuses this and the earlier drawing of Messalina but describes this as ‘one of Beardsley’s most explicit studies of evil [in masses of black and white], including the brutal lurch forward’ of her body, although not as ‘repulsive’ as the later [meaning the earlier] one (1979, p. 134). In contrast, Zatlin perceives Messalina as a tenacious woman rather than a femme fatale: ‘She is stout, less lusty than determined, and unhappy. Her breasts are naked, her pointed nipples suggesting either continued excitement or exposure to cold air’ (1990, p. 57). Furthermore, in contrast to the figures in ‘The Impatient Adulterer’ and ‘Count Valmont’, who are voyeurs *nos. 1061 below, 1029 above, Messalina acts (p. 57).

The inspiration for this drawing were ancient and contemporary. There is the asymmetrical detail balanced by areas of black and varying widths of line to suggest movement. Both arise from, for example, the unbound, whirling hair of Japanese courtesans - the ‘prototype of the Beardsley woman’s cascading tresses’ (Zatlin 1997. P. 123). These techniques were used by the seventeenth-century Japanese master print designer Hishokawa Moronobu (1618-1694) whose work Beardsley would have seen in an 1890 exhibition at London’s Fine Art Society or reproduced in magazines, such as Siegfried Bing’s ‘L’Art Japonais’ (pp. 34-5). In addition, the pattern for Messalina was a type of woman with whom the artist had contact in his childhood. Beardsley conjured, Brophy records, the ‘terrifyingly selfish, cruel and powerful empress of Rome from his wide and no-doubt terrorised early experiences of landladies, who so regularly exert their power over lodgers, about precisely such matters as returning from the bath (1976a, p. 41). Blunt and Poole state that Messalina is ‘spiritually akin’ to Picasso’s painting ‘La Gommeuse (1901, sold Sotheby’s New York December 1984; 1962, p. 9). Stokes believes that Beardsley, like Alfred Jarry and other 1890s artists, ‘used her comically, if not very originally, as a symbol of liberating excess’ (2005, p. 117).

At some point, the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Victoria and Albert Museum laid down the drawing on card; a cut-out pane; permits a small view of a sharply defined black ink sketch of a leg and the drape of a skirt edge on the verso.

Frederick Ilbery Lynch’s drawing ‘The Beardsley Business’ (c.1909, private collection, Canada) makes fun of Beardsley’s Messalina by caricaturing the (typically attenuated) Beardsley woman walking up an outdoor staircase (in search of or coming from the bath?), A fluffy boa wraps around her neck and floats over her long, black, slinky dress that starts at the lower edge of her ribcage and sports a train made from a peacock feather that stands straight up. Her head is topped by a huge mobcap from underneath which hair drips, and a candle on a wall sconce covered by a tiny shade lights her way. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | E.302-1972 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 30, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest