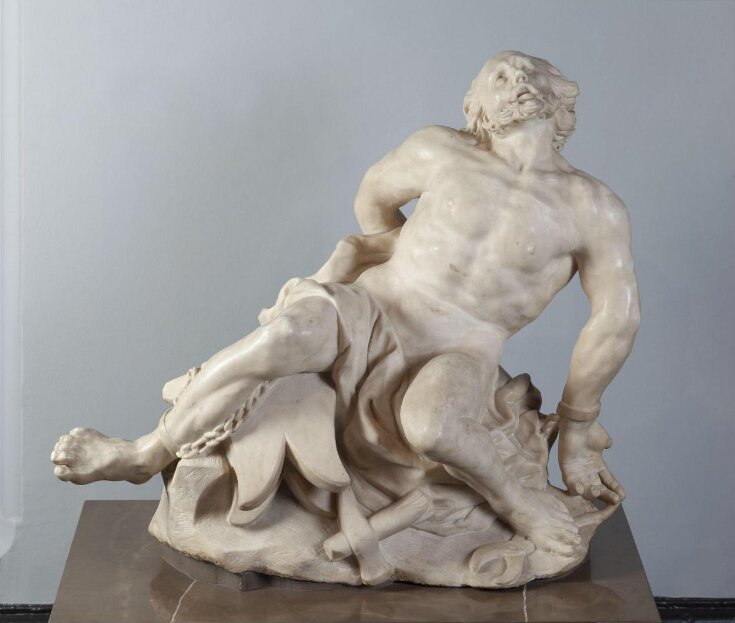

Vulcan (or possibly Prometheus) chained to a rock

Figure

ca. 1710 (made)

ca. 1710 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The figure is closely related to David's statue of St Bartholomew in the church of S. Maria di Carignano in Genoa, Italy. Malcolm Baker has suggested that it's one of the few free-standing sculptures of mythological figures to have been executed by a sculptor working in England in the first half of the 18th century'.

Although traditionally thought to represent the mythical Prometheus, chained to a rock by the god Jupiter, the figure probably represents Vulcan. The diary of Sir Matthew Decker, who saw the piece in its original setting in 1728, provides an explanation of its symbolism. Placed on the landing half-way up the main staircase, the figure was intended to be accompanied by a further figure of William III, as part of an allegorical representation of how William's arrival in England and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had averted a civil war. 'Vulcan is accordingly represented as chained, rather than fashioning the instruments of war.'

Although traditionally thought to represent the mythical Prometheus, chained to a rock by the god Jupiter, the figure probably represents Vulcan. The diary of Sir Matthew Decker, who saw the piece in its original setting in 1728, provides an explanation of its symbolism. Placed on the landing half-way up the main staircase, the figure was intended to be accompanied by a further figure of William III, as part of an allegorical representation of how William's arrival in England and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had averted a civil war. 'Vulcan is accordingly represented as chained, rather than fashioning the instruments of war.'

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Vulcan (or possibly Prometheus) chained to a rock (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | Marble |

| Brief description | Figure, marble, 'Vulcan (or Prometheus) chained to a rock', by Claude David, English, ca. 1710 |

| Physical description | Vulcan is shown chained and manacled to a rock, with his tools, a hammer, pincers and an anvil. He is bearded, looking upwards, almost naked except for a small piece of swirling drapery around his right leg. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Purchased using funds from the John Webb Trust |

| Object history | This sculpture was originally on the staircase of Narford Hall in Norfolk. It was commissioned by Sir Andrew Fountaine. Purchased at the sale of the collection of Sir Andrew Fountaine, held at Sotheby's, Parke, Bernet&Co, London, on 11 December 1980, lot 221. There it was described as Prometheus. Bought for £4460 using funds from the John Webb Trust. |

| Production | Although this sculpture was called 'Vulcan' in an early 18th century inventory, it may represent Prometheus, who was chained to a rock for stealing fire from the Gods. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | The figure is closely related to David's statue of St Bartholomew in the church of S. Maria di Carignano in Genoa, Italy. Malcolm Baker has suggested that it's one of the few free-standing sculptures of mythological figures to have been executed by a sculptor working in England in the first half of the 18th century'. Although traditionally thought to represent the mythical Prometheus, chained to a rock by the god Jupiter, the figure probably represents Vulcan. The diary of Sir Matthew Decker, who saw the piece in its original setting in 1728, provides an explanation of its symbolism. Placed on the landing half-way up the main staircase, the figure was intended to be accompanied by a further figure of William III, as part of an allegorical representation of how William's arrival in England and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had averted a civil war. 'Vulcan is accordingly represented as chained, rather than fashioning the instruments of war.' |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.3-1981 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 13, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest