| Bibliographic references | - Baker, Malcolm, and Brenda Richardson (eds.), A Grand Design: The Art of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London: V&A Publications, 1997, no. 135.

Catalogue entry by Tessa Murdoch, attrib. c.1690

- Snodin, Michael, ed., with the assistance of Cynthia Roman. Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill. New Haven and London: The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, Yale Center for British Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum, in association with Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12574-0. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the The Yale Center for British Art, 2009 and the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2010, cat.167, fig. 116, pp. 86ff (Chapter 5, by Alicia Weisberg-Roberts 'Singular objects and multiple meanings'; 268 (purchase at 1842 sale), 316

Chapter 5 discusses the cravat and considers Walpole's interest in Gibbons as carver and collector

- This object features in 'Out on Display: A selection of LGBTQ-related objects on display in the V&A', a booklet created by the V&A's LGBTQ Working Group. First developed and distributed to coincide with the 2014 Pride in London Parade, the guide was then expanded for the Queer and Now Friday Late that took place in February 2015.

- Victoria & Albert Museum: Fifty Masterpieces of Woodwork (London, 1955), no. 30.

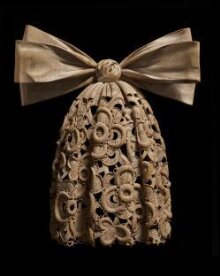

The Grinling Gibbons Cravat

GRINLING GIBBONS (1648-1721), was born in Rotterdam, of English extraction. At the age of fifteen years he came to England and attracted the attention of John Evelyn, who introduced him to Charles II. He made a great reputation as a woodcarver, and was employed also to carry out extensive schemes of wall decoration, in which highly naturalistic ornament is carved and modelled with great dexterity and in extraordinary detail. No mere illusionist craftsman, he was gifted with a remarkable feeling for composition and arrangement. Gibbons was also a sculptor of distinction and this aspect of his activities has only lately been explored.

This model of a point-lace cravat in limewood is highly characteristic of a style in part derived from his Dutch antecedents in painting, carving and the other arts. It was formerly in the possession of Horace Walpole, and hung in the room at his house at Strawberry Hill, known as the 'Tribune'. On 11th May, 1769, Walpole described to George Montagu how at a frolic of several days before he had received a number of distinguished foreign guests wearing the Grinling Gibbons cravat, in which 'the art arrives even to deception', as well as a pair of embroidered gloves which had belonged to James I. Walpole added that 'the French Servants stared and firmly believed this was the dress of an English Country gentleman'.

When Walpole's collection was dispersed in 1842 the carved cravat was bought by Miss Burdett-Coutts (later Baroness Burdett-Coutts) for a small sum. It remained in her house at No. 11 Stratton Street, until her death in 1906, when it was acquired by the late Hercules Read of the British Museum. At the sale of his collection in 1928 the cravat was purchased by the Hon. Mrs. Walter Levy (Mrs. lonides), who gave it to the Museum.

English; late seventeenth century.

H. 9 ½ in., W. 8 ¼ in. W.181-1928

- Davoli, Sylvia, Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill. Masterpieces from Horace Walpole's Collection. London: Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers Ltd., 2018. ISBN: 978-1-785541-180-6, p.85 [pp. 84-5 The Tribune]

'Two glazed cabinets flanking the altar contained many of Walpole's 'principal curiosities', a variety of objects characterised by their uniqueness. These included a wooden cravat made by Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721), Thomas Becket's reliquary casket and a dagger belonging to Henry VIII.'

'In 1769 Walpole famously wore this trompe l'oeil lace cravat, made in wood in imitation of Venetian needlepoint, to receive some distinguished visitors. The cravat was probably made by Gibbons to show potential patrons his skills and imitative ability as a carver.'

- David Esterly, Grinling Gibbons and the Art of Carving. (London, V & A Publications, 1998), pl.113, p.136

'Finely-detailed cravats and collars were a well-established arena for technical competition among marble carvers in the 17th century. [n.6] Gibbons was the first and remained virtually the only carver to extend the virtuoso treatment of this subject to wood, most famously in the full cravat later owned by Horace Walpole.'

Note 6, p.216 'A bust of Maria Barberini Dublioli (the original now lost) by Bernini's one-time assistant Giuliano Finelli included a famously delicate collar. Elaborate lacework is also seen, for example in two busts by Bernini himself: those of Thomas Baker (1638, V&A, London; although the collar here is probably by an assistant) and Louis XIV (1665, Versailles).'

- Léon Lock, 'Il Merletto veneziano scolpito alle corti d'Europa: Bernini, Gibbons, Foggini, Quellinus, in Angela Negro (ed.) Storie di Abiti e Merletti - incontri al museo sul'arte e il restauro del pizzo (Rome, Fondazione Paoloa Droghetti 2014), pp. 41-51

- Marjorie Trusted (ed.), The Making of Sculpture: The Materials and Techniques of European Sculpture (2007), pp.129-30

‘Glazes were applied to wood sculptures whose carving was exceptionally detailed. The glazes were translucent and often fairly colourless, usually consisting of animal glue or oil. They protected the surface of the wood, enhancing its natural colour and the definition of both the grain of the wood and the carving. The Cravat by Grinling Gibbons, carved in limewood in about 1690, was intricately created in imitation of Venetian lace (plate 237). As on some of Tilmann Riemenschneider’s sculptures, a translucent glaze is the only surface treatment applied to the wood. The sculpture was once in the collection of Horace Walpole (1717-97) at Strawberry Hill; he greatly admired its illusionistic effect, and apparently sometimes wore it to tease and amuse visitors.’

- OUGHTON, Frederick: Grinling Gibbons & the English Woodcarving Tradition. (London, 1979), p. 86, 136-7, 151, fig. 82

pp.86-7

Notes the cravat of point lace in the library at Hackwood (Hants, the seat of the first Duke of Bolton) brought from Abbotstone, Alresford, but doubts its authenticity as work by Gibbons. Notes the lace cravat at Chatsworth and the 'strong case for believing' that it is by Samuel Watson, not Gibbons as stated by Walpole. (pp.136-7)

Notes (p.138) the lace cravat depicted in the panel at Cullen, Banffshire, said to have come from Holme Lacey at the time of the Hereford Sale 1874.

- Geoffrey Beard, The Work of Grinling Gibbons (London, 1989), p.44

Notes Walpole's tendency to enrich Vertue's statements.

- David Green, Grinling Gibbons. His Work as Carver and Statuary (London, Country Life, 1964), pl.50

- H.Avray Tipping, Grinling Gibbons and the woodwork of his age (1648 – 1720) (London, 1914), p.83-5, pl.73

'The illustration (Fig. 73) shows it to be in fine condition and unpainted, so that the extreme dexterity of the handling is revealed, and it is difficult to believe that we are looking at limewood and not at linen threads. "The art arrives even to deception," as Horace Walpole says of it.'

Of point lace (p.84-5): 'The highly raised portions (over strands of cotton) and the large and diversified patterns appealed to Grinling Gibbons as capable of effective rendering in his favourite medium. He frequently chose this type of cravat as in incident in one of his compositions. Thus, in another of Vertue's note-books we hear of a "curious piece of carving in wood by G. Gibbons, being a point cravat in the middle, several musical instruments fruit flowers a medal hanging to a chain," while under the heading of Sir Robert Goyer's sale of pictures we read: "Here was also sold a piece of carving in wood baso relievo by Mr Gibbons, being of ornaments, fruits, flowers, martial instruments, in the middle a point Cravat most curiously wrought, said to be the piece that recommended him to K. Charles." Notes the Hackwood panel 'smothered under numerous coats of paint', and the Walpole cravat 'which so fully conforms to the standard of its age that it may be taken as typifying the curious anomaly, that at the moment when the classic spirit triumphed in our architecture, when the immutable and all-including rules of Vitruvius, as amplified and co-ordinated by Palladio, were accepted as their creed by English designers, the treatment of the components of decoration disobeyed authority and strove to be not an adaptation from Nature, but Nature its very self.'

- ON A CARVED CRAVAT BY GRINLING GIBBONS, Ralph Edwards (For the Connoisseur, June 1st 1929)

[Caption to image:] Circa 1675-80

In the second half of the seventeenth century realism triumphed over convention in all forms of English decorative art. A significant reminder of this victory may be seen in a carving by Grinling Gibbons, representing a point lace cravat, which the Hon. Mrs. Walter Levy has lately presented to the Victoria and Albert Museum. This carving, now in exhibition among the Recent Acquisitions, is eloquent of its age and of a craftsman so highly gifted that he transformed existing practice and originated a style. Yet it may be doubted if he could have accomplished what he did had not his art accorded exactly with contemporary aspirations. He gave his patrons just what they sought, but far more than they hoped to receive; and, while remaining true to his own genius, was able to gratify their naive delight in the imitation of natural forms, a baroque tendency derived from Italy. That the conditions favoured him may be seen by the most cursory survey of Post-Restoration art. In furniture, plate, embroidery and decorative painting, representation was the ideal. It may be seen within narrow limits in the crowns, oak leaves, cherubs and grape-laden vines of Charles II chairs ; on a larger scale in marquetry, where the birds and flowers were stained and shaded to a semblance of life. Realism, though quite alien to the art of the East, could not even be kept out of the English imitations of Oriental lacquer, and Stalker and Parker insist that their designs for "Japanning" are accurate representations of "Indian life." On silver plate, strapwork ornament of Flemish and German inspiration was replaced by embossed cornucopi and festoons of fruit and flowers. For embroidery in wools on canvas, a characteristic Late Stuart art, the patterns are freely drawn from nature ; while the laborious imitation of familiar things is carried to extravagant lengths on caskets find picture frames worked in silks.

This striving after verisimilitude may also be observed in architectural decoration, which offered an almost limitless field. For interior plasterwork Inigo Jones, John Webb and their school had enriched soffits with fruit and flowers and used boldly designed swags for their friezes ; generalising the detail and placing the main emphasis on spacing and arrangement. After them the decoration was seldom subordinated to the moulded ribs: it overflowed the ceiling, the fruit and flowers, of which the species are easily recognised, being deeply undercut to imitate nature. The wall space provided an irresistible opportunity for bringing the external world within doors, and in Grinling Gibbons the age possessed a craftsman supremely fitted to gratify its passion for naturalism. Choosing soft woods like pear and lime, he clothed the great projecting panels with birds, fruit and flowers, pea-pods, ears of corn and sprays of foliage, carved and modelled with amazing dexterity. He had a real instinct for balance and proportion; but, as Mr. Avray Tipping has said, " the whole of his marvellous skill of hand and eye was given over to exact imitation of natural forms, and the more the material in which he wrought lost its own character and took over that of the object it simulated, the greater the artistic triumph." His copious fancy turned to account not only the varied and abounding life of garden and field, but also details of costume, musical instruments and weapons of the chase.

Among his crowded swags of flowers he was fond of introducing some familiar thing to hold the spectator spellbound by the fidelity with which it was represented. And this frank appeal to the delight in representation won him the highest praise. It is significant that his contemporaries dwell long upon his "studious exactness," the miracles of execution with which he deceived the eye, and have little to say of the ability with which he conceived and carried out vast schemes of decoration. The ill-founded tradition that he set above his door a basket of flowers winch trembled as the coaches rolled by expresses the tribute of those who saw in his work a new kind of sensation. So Luttrell, sharing the common view, will have it that Evelyn showed Charles II " a point cravet " as a specimen of the artist's skill ; though Evelyn had plainly declared that it was the " Crucifixion of Tintoret." It was by a cravat that Gibbons was commemorated in the vast and miscellaneous collection of Horace Walpole, a curious toy complete in itself, wrought as a demonstration of what could be done by that unerring hand. There are carvings of just the same character at Hackwood, Petworth and Cullen; but each forms part of a decorative composition and takes its place amid the flowers and foliage. This cravat, given to Walpole by Grosvenor Bedford, was hung upon the wall in the apse of the " Tribune " at Strawberry Hill, described by the owner as " a vaulted room painted stone colour —the roof from the chapter-house at York . . . with the painted windows gives it the solemn air of a side chapel.'

On May 11th 1769, over a hundred and fifty years ago, Walpole writes to George Montagu that on the previous Tuesday Strawberry was in " great glory," for he was giving a festino or grand reception. He entertained four and twenty guests, including M. and Mme du Chatelet, the Duc de Liancourt, the Spanish and Portuguese Ministers. "They arrived at two. At the gates of the Castle I received them, dressed in the cravat of Gibbon's carving, and a pair of gloves embroidered up to the elbows that had belonged to James the First. The French servants stared, and firmly believed this was the dress of English country gentlemen." And so, in respect to the neckwear, it was, half a century before, when Venetian point lace cravats were fashionable throughout Europe. This specimen, bell-shaped and tied at the throat by a bow of ribbons, is in the style of about 1675 ; but by 1700 the tie, or cravat-string, was discarded, and the folds were larger, falling in picturesque disorder. In this early fashion the pleasing contrast of vertical and horizontal lines, the formal folds, the rich and intricate pattern of the lace, padded and raised at the edges with a charming play of light and shade, seems to have taken Gibbons' fancy, causing him to delight in repeated renderings of this piece of finery; though a single slip of the chisel would be fatal. Here, in Walpole's words, "the art arrives even to deception."

This carving was Lot 99 on the fifteenth day of the Strawberry Hill sale in 1842, when it was bought by the Baroness—then Miss—Burdett-Coutts for nine guineas. It remained at No. 1, Stratton Street until her death, when the late Sir Hercules Read acquired it. At the sale of his collection in November of last year Mrs. Levy purchased the cravat and gave it to the Museum, where it joins the kingwood cabinet with ivory statues designed by Walpole in 1743, which formerly hung near to it in the Tribune at Strawberry. Both objects from that inestimable collection have been saved for the nation by private generosity. This cravat and some fragments of decoration from Cassiobury presented by Mr. Harry Lloyd are all that the Museum possesses of "the stupendous and beyond all description the incomparable carving of our Gibbons."

- Avril Hart, Ties (V&A, London 1998), p.18, pl. 7

Image caption: British, 1670s

'A rather ununusual representation of a cravat dating from the period was that carved in limewood by Grinling Gibbons. the carving appears to represent a ready-made cravat, where bow and cravat-ends were an item and fastened at the back of the neck. The lace is finely carved and is recognisable as Venetian gros point. James II wore exceptionally fine lace on his wedding outfit, and interestingly here too the cravat-ends are of Venetian gros point.'

- Tony Webb, Master Carver, St Paul's Cathedral; '50 Years of Following In Grinling Gibbons' Tool Cuts' in V&A Conservation Journal, October 1998 Issue 29

- Comparable limewood cravat-carving in the collection of Chatsworth House, Derbyshire; possibly by Samuel Watson (1662-1715) who worked there in Gibbons's style between 1691-1711.

- VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM REVIEW OF THE PRINCIPAL ACQUISITIONS DURING THE YEAR 1928, ILLUSTRATED (LONDON: PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION, 1929), p.82

In the course of the year the collection of English furniture and woodwork received some notable additions which greatly enhanced its representative character: among them being several gifts of outstanding importance….

A CARVING BY GRINLING GIBBONS.

A brilliantly executed limewood carving by Grinling Gibbons in the form of a point-lace cravat, given by the Honourable Mrs. Walter Levy, is not only a remarkable specimen of craftsmanship, but has most interesting associations. It was in the collection of Horace Walpole at Strawberry Hill, being a present to him from a friend. Writing to George Montagu on 11th May 1769, concerning a large party which he had lately given, Walpole relates that he received his guests " at the gates of the Castle…dressed in the cravat of Gibbons carving, and a pair of gloves embroidered up to the elbows, that had belonged to James I. The French servants stared, and firmly believed this was the dress of English country gentlemen." The cravat was included in Walpole's sale in 1842, when it was bought by" Miss B. Coutes "for nine guineas. Carved cravats of similar character were introduced by Gibbons into several of his decorative compositions, and in such imitations, as Walpole says, "the art arrives even to deception."

|