Fashion Design

1912 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

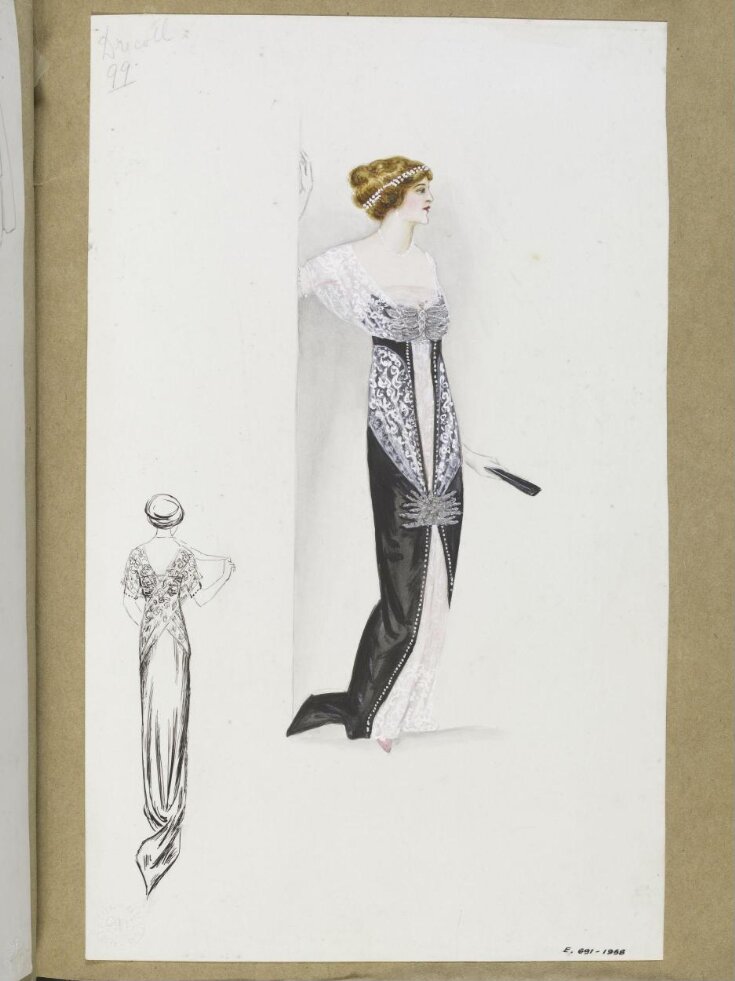

Black satin evening gown with draped white lace fichu and overskirt, white underdress. Silver bead embroidery.

One of 38 designs bound in a volume from a group of 248 fashion designs for 1912.

One of 38 designs bound in a volume from a group of 248 fashion designs for 1912.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Pencil, pen and ink, and watercolour |

| Brief description | Madame Handley-Seymour after Drecoll. Black satin evening gown with draped white lace fichu and overskirt, white underdress. Silver bead embroidery. London. One of 38 designs bound in a volume from a group of 248 fashion designs for 1912. |

| Physical description | Black satin evening gown with draped white lace fichu and overskirt, white underdress. Silver bead embroidery. One of 38 designs bound in a volume from a group of 248 fashion designs for 1912. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Credit line | Given by Mrs. Joyce Whitehouse |

| Object history | Elizabeth Handley Seymour, née Elizabeth Fielding, (1867-1948) was a court-dressmaker whose atelier was based at 47 New Bond Street. She designed gowns for the Court and Society during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, most famously the wedding dress for the Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother) and later, her Coronation dress. These volumes of fashion designs were donated by Elizabeth's daughter, Mrs. Joyce Whitehouse in 1958. These sketches would have been shown to prospective clients and also sent out to customers for approval, with a charge made upon the customer if the sketches were not returned within a few days' time. Many of the sketches depict Paris models designed by leading French couturiers of the day, many of which are annotated clearly with the original designer's name. Prior to the 1920s, the copying of couture models, whilst problematic, was a quite widespread practice and many high end dressmakers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century openly copied couture gowns for their customers at prices which were rather lower than those charged by the notoriously expensive House of Worth or equivalent establishments. Elizabeth Hawes (1903-71), the American author, activist, and dress designer who combined a highly underrated fashion design talent with a sharply observant social conscience, started her fashion career in Paris in 1925 at her friend's mother's dressmaker, which was a high end copy house making illegal copies of gowns by the likes of Chanel and Vionnet for non-French speaking American clients so that they could fill their wardrobes with accurate copies of designer dresses, often in identical fabrics, for a fraction of the price. Although this was highly illegal, and Hawe's conscience led her to leave her employers after a year and a half, many clients had no qualms about buying or ordering copies. The practice would have been more difficult to police outside Paris. Although many of the designs are openly annotated with their original designer's name, including Handley-Seymour's own, they are drawings rather than actual garments and this does not indicate that Handley-Seymour actually made up replica dresses. However, it was necessary for many London-based designers to offer Paris models in order to survive. Norman Hartnell (1901-1979), the Royal dressmaker who opened his dress business in London in the 1920s, recalled how clients would look at his designs, approve the style and fabrics, take a fitting, casually enquire who had designed it, and promptly cancel the order upon discovering it was not a Paris model by Lelong or Patou. He described this as "the unforgivable disadvantage of being English in England". Handley-Seymour was therefore following a practice common with many high end London dressmakers of offering Paris models from her own workrooms. Although this may well have been of dubious legality, it was necessary in order to survive. Her albums offer a remarkable record and overview of high end fashion design between 1910 and 1940. Among the designers represented are a number of sketches of dresses and coats by Paul Poiret, whose work was considered very avant-garde and daring in the 1910s. This shows that Handley-Seymour's clients were very fashion conscious, expecting to be offered the most stylish, up-to-date garments. Very early designs by Gabrielle Chanel and Edward Molyneux appear in the album, alongside designers such as Jeanne Hallée and Jenny, who although little-known now, were rated with the most desirable couturiers of the time. Among the other designers represented are Agnes, Bechoff-David, Gustave Beer, Boué Soeurs, Bulloz, Callot Soeurs, Charlotte & Germain, Doeuillet, Doucet, Bernard Gougan, Jeanne Lanvin, Madeline & Cie, Paquin, Premet, Renée, Roland, and Worth. When Elizabeth died in 1948 she had been married for 47 years to Major James Burke Handley-Seymour, so she must have been born c.1881 and married 1901. There is an Elizabeth Fielding identifying herself as a court dressmaker in the 1901 census (RG 13/83 f15 p19), aged 28,which would suggest a credible birth date of 1873 if it is the same Elizabeth Fielding. - Daniel Milford-Cottam (July 2012) Elizabeth Handley-Seymour's great-nephew contacted the Museum in April 2016 with biographical details on his great-aunt to clarify her history. She was born in Blackpool , Lancashire, in 1867, and moved to London during the 1890s. While she appears in the 1881 and 1891 cenusus records for Blackpool with the correct ages of 13 and 23; the 5 year discrepancy in her age on the 1901 census is perhaps explained by the fact that she was rather older than James Handley-Seymour, who she married that same year. - Daniel Milford-Cottam, 15/04/2016 |

| Bibliographic reference | Victoria and Albert Museum Department of Prints and Drawings and Department of Paintings Accessions 1957-1958 London: HMSO, 1964 |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | E.691-1958 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 30, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest