Francis Williams, the Scholar of Jamaica

Oil Painting

ca. 1760 (made)

ca. 1760 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

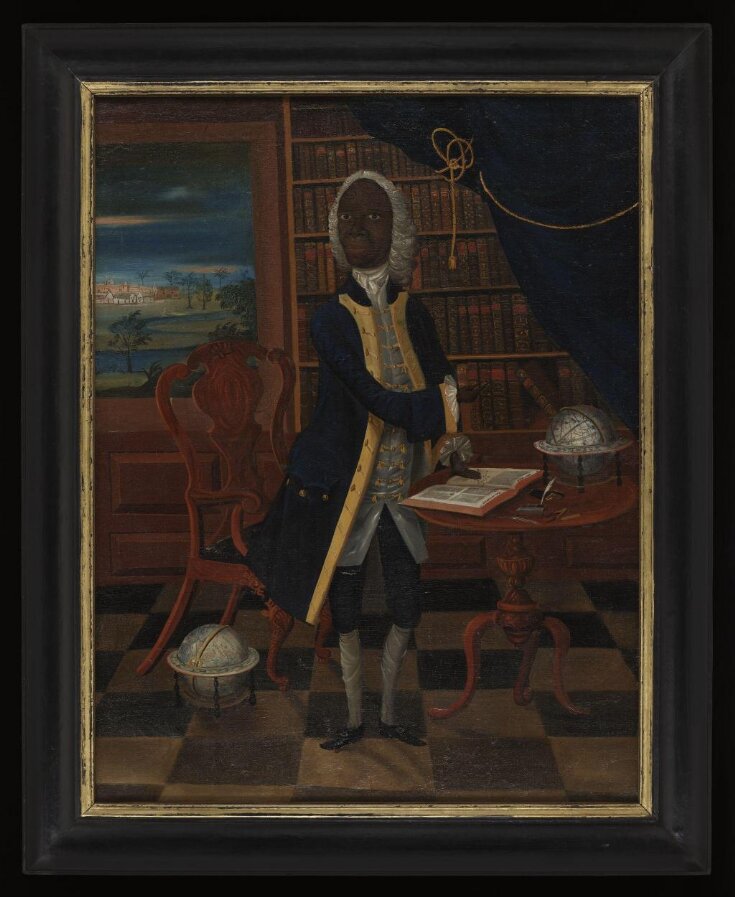

In the 18th century portraits painted in oil were regarded as a sign of achievement and social status. Beyond representing the sitter’s likeness, the careful choice of setting and objects were used to express character and invisible ‘qualities’.

Subject

Francis Williams (about 1690 – 1762) was a free Black Jamaican landowner, scholar, writer and teacher. He was educated at least partially in England, where he also studied law – becoming the first known Black member of Lincoln’s Inn – and attended meetings of the Royal Society when Isaac Newton was its president.

Williams’ portrait follows 18th-century European conventions in representing scholarly gentlemen. He is shown wearing a formal coat and breeches, standing in his elegant, book-lined study. A globe of the world has been placed on the floor, and a celestial globe on the table. Williams rests his hand on an open copy of Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica and dividers and other drawing instruments lie next to it. All this, including the wider choice of authors in the library, conveys Williams’ interest and competence in astronomy, mathematics and geography as well as rhetoric, logic and grammar.

A landscape, thought to represent Spanish Town by the Cobre River, is visible through the window. This locates Williams in Jamaica, after his return from England to take over responsibility for his family’s estates. The sky above appears to be captured at dusk with colourful clouds.

The painting’s finish and insecure handling of perspective, especially in the depiction of Williams’ legs and the table, have raised questions regarding the training of the unknown artist responsible for this picture. While the artistic ecologies of the Caribbean during the 1700s are currently under investigation it has been suggested that this could be a self-portrait. Alternatively, the British-born painter William Williams (1721 – 1791) has been proposed as the possible artist of this picture. Research into the identity of the artist is ongoing.

In the 18th century portraits painted in oil were regarded as a sign of achievement and social status. Beyond representing the sitter’s likeness, the careful choice of setting and objects were used to express character and invisible ‘qualities’.

Subject

Francis Williams (about 1690 – 1762) was a free Black Jamaican landowner, scholar, writer and teacher. He was educated at least partially in England, where he also studied law – becoming the first known Black member of Lincoln’s Inn – and attended meetings of the Royal Society when Isaac Newton was its president.

Williams’ portrait follows 18th-century European conventions in representing scholarly gentlemen. He is shown wearing a formal coat and breeches, standing in his elegant, book-lined study. A globe of the world has been placed on the floor, and a celestial globe on the table. Williams rests his hand on an open copy of Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica and dividers and other drawing instruments lie next to it. All this, including the wider choice of authors in the library, conveys Williams’ interest and competence in astronomy, mathematics and geography as well as rhetoric, logic and grammar.

A landscape, thought to represent Spanish Town by the Cobre River, is visible through the window. This locates Williams in Jamaica, after his return from England to take over responsibility for his family’s estates. The sky above appears to be captured at dusk with colourful clouds.

The painting’s finish and insecure handling of perspective, especially in the depiction of Williams’ legs and the table, have raised questions regarding the training of the unknown artist responsible for this picture. While the artistic ecologies of the Caribbean during the 1700s are currently under investigation it has been suggested that this could be a self-portrait. Alternatively, the British-born painter William Williams (1721 – 1791) has been proposed as the possible artist of this picture. Research into the identity of the artist is ongoing.

Delve deeper

Discover more about this object

visit

V&A trail: Britain and the Caribbean

In this trail Avril Horsford, one of our African Heritage Gallery Guides, explores the traumatic history that connects Britain and the Caribbean, resulting from the lucrative and brutal trade in enslaved Africans, taken to work on sugar plantations in the 17th century. These objects reveal...

interact

Francis Williams – a portrait of a writer

This portrait of the Jamaican intellectual and writer Francis Williams was painted around 1760 by an unknown artist. It was acquired by the V&A in 1928.

watch

The puzzle of portraits: Francis Williams and Vanley Burke

"It's really important to us, as a museum, to lean into what is not known" – Dr Christine Checinska, 2023

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Title | Francis Williams, the Scholar of Jamaica (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | Oil on canvas |

| Brief description | Anonymous portrait of Francis Williams of Jamaica, oil on canvas. Possibly a self-portrait or the work of an artist active in the Caribbean in about 1760, such as William Williams (1721 – 1791). |

| Physical description | The oil painting is slightly smaller than an 18th-century standard ‘three-quarter size’ canvas (76.2 x 63.5 cm). The Jamaican landowner and scholar Francis Williams is shown full-length, standing at a small table in his study. His body is turned slightly to the right, his head to the left. Williams’ eyes are looking straight ahead, firmly holding the viewer’s gaze. With his right hand, William points to the bookshelves behind him while his left rests an open copy of Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica atop the table. (Fara Dabhoiwala has recently identified this as the book’s 3rd edition published in 1726) To the left, in front of a window, stands a wooden chair. On the right, a gathered blue curtain partially obscures the shelving. The floor is tiled in black and white. Williams is dressed in high-quality navy-blue broadcloth coat and breeches. The woollen coat is faced in yellow and has gold metal buttons (probably gilded metal). Underneath, Williams wears a white silk satin waistcoat, with gold frogged fastening, or fastening à la hussar. Above his buckle shoes, his white, probably silk, stockings appear loose. Williams wears a bob wig, white linen neckcloth and very fine white linen cuffs, their translucency particularly well captured over his right wrist. The accoutrements of Williams’ education and learning - a celestial and a territorial globe, dividers and other drawing instruments - are laid out on the table and floor. The bound books lining the shelves behind him include works by Newton, Locke, Milton, Cowley, Boyle, Sherlock and Rapin, and the architect Andrea Palladio as well as most likely Johnson’s Dictionary, published in 1755, which would provide a post quem date for the portrait. But while the painting clearly locates Williams within the tradition of European scholarship and highlights the scientific networks associated with his time in London, it also - by virtue of the open window that reveals the tropical landscape of Spanish Town, the river bank and colourful sky - sets him firmly within a Jamaican setting. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Gift of Viscount Bearsted M.C. and Spink and Son Ltd. through the National Art Collections Fund, 1928. |

| Object history | Gift of Viscount Bearsted M.C. and Spink and Son Ltd. through the National Art Collections Fund, 1928. Prov: Major H. Howard of Hampton Lodge, Seale, Farnham, direct descendant of Edward Long, author of 'A History of Jamaica'; purchased by Spink and Son Ltd. for £250 and given to the V&A in 1928 on the condition at Viscount Lord Bearsted paid Spink and Son Ltd. £150. |

| Historical context | HISTORICAL CONTEXT While a previous date of about 1740 was first suggested in 1928 and previously supported yet not definitively decided by considerations of the sitters dress and the furniture in the portrait, the recent identification of one of the volumes on the library shelves as Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) now places the date around 1760. Artist: The painting’s finish and insecure handling of perspective, especially in the depiction of Williams’ legs and the table, have raised questions regarding the training of the unknown artist responsible for this picture. The suggestion that the painting is satirical has been superseded. With the artistic ecologies of the Caribbean during the 1700s currently the subject of research, it has been suggested that this could be a self-portrait. Alternatively, the British-born painter William Williams (1721 – 1791) has been proposed as the possible artist of this picture. Research into the identity of the painter is ongoing. Many writers have commented on the unusual proportions of the figure and objects in the painting. Images of the painting taken using Infrared reflectography have revealed underdrawings, including projection lines on the checkerboard floor which were possibly drawn with a ruler. By continuing these lines, the vanishing point reveals itself to be Williams’ face. This may be an indication that the artist was relying heavily on drawings manuals but distorted the figure’s proportions in the process. Biography: Francis Williams (about 1690–1762) Francis Williams is the first known black writer in the British Empire. Much of what is known about him is recorded in The History of Jamaica (1774), a racist publication by Edward Long (1734–1813). Long was a British colonial administrator in Jamaica and a vocal advocate of slavery, who owned plantations and lived there from 1757 to 1769. Francis Williams’ date of birth is not known, but when he died in 1762 he was reportedly ‘aged seventy or thereabouts’ (Long, History of Jamaica). Francis was the son of John and Dorothy Williams, who were both enslaved. John Williams was not emancipated until 1697: if Francis was born around 1690, as is generally assumed, he was therefore also born into slavery. Following emancipation, John Williams became a successful and wealthy merchant, buying land and slaves of his own. Francis had two elder brothers, John and Thomas, and a sister, Lucretia. As emancipated Black inhabitants of Jamaica, the Williams family were free to live and work, but they were not automatically granted the same legal and civil rights as white Jamaicans. In February 1708 John Williams succeeded in having a special local act passed which granted him the right to trial by jury and prevented enslaved people from testifying against him. In 1716 John Williams successfully had this act extended to include Dorothy, and their sons John, Thomas and Francis. Their daughter, Lucretia, was not included. When John Williams died in 1723, his estate was valued at £16,319 Jamaica Currency (over £12,000 sterling). This included land, enslaved labourers and children, and debts owed to Williams by prominent members of Jamaican society. Francis Williams was educated at least partially in England. He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn on 8 August 1721.Royal Society minutes show Williams was present at Royal Society meetings, but, according to an anonymous editorial comment in the Supplement of the Gentleman’s Magazine 1771, this scientific organisation denied him full membership 'on account of his complexion'. Williams returned to Jamaica after the death of his father in 1723 and took over the family estates. It appears that Williams spent the rest of his life in Jamaica; he ran a school in Spanish Town, teaching Black students reading, writing, Latin and mathematics. Williams became a well-known public figure in Jamaica and England, as a rare example of a black person granted the education usually reserved for white people. Williams wrote Latin poetry, including an ode to the new Governor of Jamaica, George Haldane, preserved in Long’s History of Jamaica. Long sought to discredit Williams through critique of this poem, but Long’s interpretation has been judged to be intentionally misleading (Lindo, 1970 , Hall, 2024). Recent academic work centred on the iconography of the portrait has foregrounded Williams’ skill as an astronomer and linked the painting to the (re-)appearance of Halley’s Comet over Jamaica in 1759 (Dabhoiwala 2024) It would seem that Williams did not share his father’s flair for business, and instead lived on the family fortune, supplemented by a modest income from teaching. When Williams died in 1762 he was living in rented accommodation, and his property reduced to £694 and 19s Jamaica Currency (around £500 sterling). Williams was ridiculed by racist white contemporaries such as Edward Long and David Hume, the latter describing him as ‘like a parrot who speaks a few words plainly’ (Hume, Of National Characters, 1748). He was also used as an argument in favour of the abolition of slavery by people such as Henri Grégoire and Robert Boucher Nickolls. Williams owned enslaved people, he was not an abolitionist. However, as a pioneering black writer, his very existence challenged the ideological basis of trans-Atlantic slavery which relied upon the myth that black people were inferior intellectually and socially to white people. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Place depicted | |

| Summary | Object Type In the 18th century portraits painted in oil were regarded as a sign of achievement and social status. Beyond representing the sitter’s likeness, the careful choice of setting and objects were used to express character and invisible ‘qualities’. Subject Francis Williams (about 1690 – 1762) was a free Black Jamaican landowner, scholar, writer and teacher. He was educated at least partially in England, where he also studied law – becoming the first known Black member of Lincoln’s Inn – and attended meetings of the Royal Society when Isaac Newton was its president. Williams’ portrait follows 18th-century European conventions in representing scholarly gentlemen. He is shown wearing a formal coat and breeches, standing in his elegant, book-lined study. A globe of the world has been placed on the floor, and a celestial globe on the table. Williams rests his hand on an open copy of Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica and dividers and other drawing instruments lie next to it. All this, including the wider choice of authors in the library, conveys Williams’ interest and competence in astronomy, mathematics and geography as well as rhetoric, logic and grammar. A landscape, thought to represent Spanish Town by the Cobre River, is visible through the window. This locates Williams in Jamaica, after his return from England to take over responsibility for his family’s estates. The sky above appears to be captured at dusk with colourful clouds. The painting’s finish and insecure handling of perspective, especially in the depiction of Williams’ legs and the table, have raised questions regarding the training of the unknown artist responsible for this picture. While the artistic ecologies of the Caribbean during the 1700s are currently under investigation it has been suggested that this could be a self-portrait. Alternatively, the British-born painter William Williams (1721 – 1791) has been proposed as the possible artist of this picture. Research into the identity of the artist is ongoing. |

| Associated object | P.83:1-1928 (Part) |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | P.83&A-1928 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 1, 2001 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest