| Bibliographic references | - Lambert, Susan, Drawing: Technique & Purpose, London, 1981. p.42.

- Ward-Jackson, Peter, Italian Drawings. Volume I. 14th-16th century, London, 1979, cat. 18, p. 24-26, illus.

The following is the full text of the entry:

VERROCCHIO, ANDREA DEL (1435-88)

18

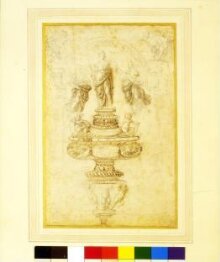

Design for a monument in the form of a covered bowl, with a personification of Justice on the cover and other figures

Black lead pencil, partly gone over in pen and ink and wash

10 ¾ x 6 7/8 (273 x 175) 2314

PROVENANCE Sir T. Lawrence (Lugt 2445); S. Woodburn (sale, Christie, 8 June 1860, lot 1053, bought for the Museum)

LITERATURE K.Clark in The Vasari Society for the reproduction of drawings by old masters, 2nd S., pt X, 1929, no. 3; R. van Marle, The development of the Italian schools of painting, The Hague, 1929, 9, p. 582, footnote; B. Degenhart, 'Die Schiiler des Lorenzo di Credi' in Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst, N.S., 9, 1932, p. 105, n. 65; B. Berenson, 'Verrocchio e Leonardo, Leonardo e Credi' in Bollettino d'Arte, 27, 1933-34, pp. 262-63, fig. 27; BB. 1938, no. 699 B and fig. 130, also pp. 68 and 75 (footnote); U. Middeldorf in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 3, 1934, pp. 57-8 (illustration on p. 55); E. Moller, 'Verrocchio's last drawing' in The Burlington Magazine, 66,1935, pp. 193-94; L. Dussler, article on Verrocchio in Thieme-Becker, 34,1940, p. 295; W. R. Valentiner, Studies of Italian Renaissance sculpture, 1950, p. 119, footnote: Gigetta Dalli Regoli, 'Problemi di grafica crediana' in Critica d'Arte, 12, no. 76, 1965, p. 41 : the same, Lorenzo di Credi, Pisa, 1966, pp. 133-34, catalogue no. 66 and pl. 53: G. Passavant, Verrocchio, London, 1969, pp. 60-2 and pl. 194, catalogue no. D.11, pl. 101; S. Grossman, Master Drawings, 10, no. 1, 1972, p. 18, fig. 5; C. Seymour, The sculpture of Verrocchio, London, 1972, pp. 28-9, pl. 24; Wendy Stedman Sheard, article on genesis of Vend ram in tomb, to be published 1977, probably in Art Bulletin.

In the middle of the sheet there is a bowlshaped receptacle, with a cover, standing on a foot. The foot is supported by three putti on a console, which shows that the monument was meant to be placed against a wall and carried out in relief. A figure of Justice with sword and scales stands on the cover of the bowl, flanked by two other allegorical figures, which fly or float in space, unsupported, unless the faintly drawn horizontal lines beneath their feet represent ledges. It is difficult to make out what the attributes of these figures are, but Passavant may be right in stating that the one on the left holds a sheaf of corn and a cornucopia and that the other holds a laurel wreath. The second figure appears to be winged. A pair of putti seated on the lid of the bowl below Justice support a shield each, one of which is charged with a fess. They also hold an unrolled scroll between them, which was evidently intended to bear an inscription. A medallion on the bowl contains a representation of the Lion of St Mark.

All this is framed in a coffered arch resting on consoles. This part of the drawing is so lightly and sketchily drawn that it is difficult to read: but the vertical lines below the consoles probably represent the folds of a curtain. There are more, slight indications of a curtain inside the arch. It was perhaps intended to be gathered up into a roll on the under side of the arch and allowed to fall in pleats on each side, as in Antonio Rosselino's monument to the Cardinal of Portugal in S. Miniato at Florence, executed in the 1460s. Two pairs of putti in lively movement are poised on the imposts of the arch.

The drawing was originally made in hard black chalk, but ink and wash have been applied to it in two different stages. First the three allegorical figures and three out of the five putti have been touched with pen and brush, very sensitively and delicately, perhaps by the original artist. Then a different hand has gone over the lines of the bowl with a pen, in a darker ink, giving this part of the drawing a heavy outline, very different from the light touches of pen and brush in the figures. There are signs that the original design here has been altered, The straight horizontal chalk lines visible in the blank scroll held by the seated putti and in the rim of the cup suggest that the object represented here in the original design was straight, not curved. The alteration might have been made unintentionally, through a misreading of the faintly drawn original, or deliberately, in order to adapt the design to a different use.

The perspective in this part of the drawing is faulty, inasmuch as there is no fixed viewpoint, the bottom of the bowl being above eye level, while the top is below eye level. It is hard to believe that in an age when correct perspective was a cult, such mistakes would have been made by the skilful artist who drew the figures. Our conclusion must be that the re-working is by another artist, who departed from the original design and perhaps even changed its purpose. So far as it can be read, the original design seems to have been for a sculptured monument on a substantial scale, embodying a sarcophagus standing on a single foot. The sarcophagus may have had rounded ends as well as a swelling profile; but the longer sides were probably straight in plan, as the straight horizontal chalk lines under the inked lines seem to indicate. The form would have suggested a comparison with a bowl, but could not have been mistaken for one. In the re-worked design the object is plainly a bowl with a cover, which can only with difficulty be accepted as a sarcophagus. A bowl is most inconveniently shaped to contain a recumbent human body and is only suitable for ashes. It is a question whether any artist of the time would have designed a sarcophagus in a shape so eccentric and inappropriate or would have flouted the Church's ban on cremation by using a receptacle associated with that pagan custom instead of a sarcophagus of the traditional type. The most likely explanation is that the design in its present form is the invention of the artist who re-worked the drawing, turning the sarcophagus of the original into a bowl, which might even have been intended to be carried out by a goldsmith.

A drawing in the Louvre shows a similar design and must have been based on ours. (Inv. no. 1788; BB. 720; Degenhart, loc. cit., p. 105, pl. 105; Moller, loc. cit., p. 193, fig. B; Dalli Regoli in Critica d'Arte, loc. cit., pl. 43, and Lorenzo di Credi, p. 163, no. 137, pl. 181). Among the features that it has in common with our drawing is a shield charged with a fess. Here the bowl is viewed from underneath and is shown in such a way that it can only be understood as circular in plan. It consequently does not look in the least like a sarcophagus. The figure of Justice and two other allegorical figures have been borrowed from our drawing, but the last two, instead of floating in the air, stand sedately on the lid of the bowl, in place of the pair of putti, who have been suppressed. The drawing of the figures is less lively and less fluent than in our drawing. The whole design is weaker. The blind arch, which gives a stable framework to the monument on our sheet, is replaced by a curtain draped behind the bowl to form a baldacchino, in a manner more commonly seen in Venetian than in Florentine sculpture. Against this insubstantial background the monument is suspended in space without any visible support. There is, it is true, a bracket underneath, as in our drawing, but it performs no function: the two putti standing on it merely support a shield, oblivious of the heavy-looking mass poised above their heads. In our drawing the three putti on the bracket convey an invigorating sense of muscular thrust as they strive to hold up the burden.

The Louvre drawing was in Vasari's collection and his cartouche ascribing it to Lorenzo di Credi is still on it. Degenhart prefers to give it to Gianjacopo di Castrocarro, a pupil of Credi. But Berenson and Dalli Regoli support Vasa ri's attribution. Dalli Regoli compares it with a drawing attributed to Credi in the Uffizi, which belongs to a group of designs for altars discussed here under no. 2.

Our drawing, described as a design for a chalice, was ascribed to Leonardo da Vinci in the Woodburn sale. It was first attributed to Verrocchio by Meder and Steinmann in 1928, according to a note in the Department. Clark tentatively suggested the name of Benedetto da Maiano, but the other writers mentioned in the bibliography have either accepted Verrocchio as the author or given the drawing to Credi, his favourite pupil. The protagonists of Credi are Berenson and Dalli Regoli. The latter includes the sheet in her catalogue of Credi's drawings, but admits that he may have worked over a drawing by Verrocchio. Berenson also acknowledges the influence of Verrocchio. Moller deduces from the presence of the Lion of St Mark that the drawing is that design for a Doge's tomb which Vasari says belonged to Vincenzo Borghini; and he argues from the charge of a fess on one of the heraldic shields that the Doge was Andrea Vendramin, who died in 1478, but had no monument till after 1490, This hypothesis is supported by Passavant, who dates the drawing about 1485, and by Seymour. It is certainly possible that Verrocchio may have had such a commission while he was working on the Colleoni monument in Venice.

The view that he was the author of the design in its original form is on the whole supported by the stylistic evidence. The trio consisting of Justice between the two flying or floating figures is reminiscent of the trio consisting of Cardinal Forteguerri between two flying angels in the clay sketch for the Forteguerri monument in our Museum (PopeHennessy and Lightbown, no. 140, pl. 162). The handling of the pencil also suggests Verrocchio, in so far as we know him as a drafts man and can distinguish him from Credi. The putti sporting on the imposts of the arch are very like the playing boys on both sides of a well known sheet in the Louvre that can confidently be attributed to Verrocchio on the strength of some verses in his praise inscribed on the paper in a contemporary hand (BB 2783, figs. 122 and 123: Passavant, p. 193, D. 11, pl. 98 and 99). Not only are the putti drawn with the same energetic and economic strokes, but one of them, the one on the far left in our sheet, is almost the same boy, in the same pose, as the second boy from the left on the recto of the Paris drawing, he who, in Berenson's words, 'runs as if pretending to be frightened.

It is difficult to say whether Verrocchio or Credi was responsible for the second stage in the evolution of the drawing, that is to say for the strengthening of the outlines of the human figures with the pen and the application of the wash. There are parallels for this finely executed work in other drawings of the same school, notably in the study in the Louvre for the St John the Baptist in the Pistoia altarpiece (Berenson 725 and fig. 138: Dalli Regoli, Lorenzo di Credi, p. 105, no. 13 and fig. 30: Passavant, p. 191, no. D.4 and fig. 91). The trouble is that though we may claim that the analogous parts of our drawing are by the same hand, opinions are still divided on the question whether the St John the Baptist and some other studies like it are by Verrocchio or Credi.

The third stage in the evolution of our design, the re-drawing of the sarcophagus is certainly not by Verrocchio. Is it by Credi? The work seems too coarse for him, but if the Louvre design derived from ours is by him, then it is possible, stylistically, that he may have re-worked our drawing. In that case the history of the two drawings can be summarised in a few words by saying that our drawing is a design for a monument to a Venetian doge, planned by Verrocchio while he was in Venice; that it was subsequently altered by Credi, who evidently admired the conceit of comparing a tomb to a bowl so much that he exaggerated the likeness; that he then drew a fresh design, on the sheet in the Louvre, drastically simplifying Verrocchio's composition and re-fashioning the receptacle in such a way as to remove all doubt that it was intended to be in the form of a round bowl. The final design, in spite of its borrowings from Verrocchio and its reminiscences of certain curtained Venetian wall monuments, bears so little resemblance to a tomb that it is a question whether Credi may not have adapted Verrocchio's unused design for a new purpose, as yet unguessed, conceivably for a processional banner, as Degenhart conjectured.

- pp 136-8

Donatello, Michelangelo, Cellini : sculptors' drawings from Renaissance Italy, exh. cat. ed. by Michael W. Cole, Boston, Isabella tewart Gardner Museum - London : Paul Holberton, 2014, cat. 5, pp. 136-7.

- p. 125

Pietro C. Marani and Maria Teresa Fiorio, eds., Leonardo da Vinci 1452-1519: the design of the world, Milan, 2015, cat.

- Il designo fiorentino del tempo di Lorenzo il Magnifico, A. Petrioli Tofani ed., Florence, 1992, p. 244, illus.

- Renaissance Florence. The Art of the 1470s, exh. cat. ed. by P. L. Rubin and A. Wright, London, National Gallery, 1999, cat. 11, pp. 146-147

- E. Möller, 'Verrocchio's last drawing, The Burlington Magazine, 66, 1935, pp. 193-5.

|