Tombstone

circa 1300-10 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

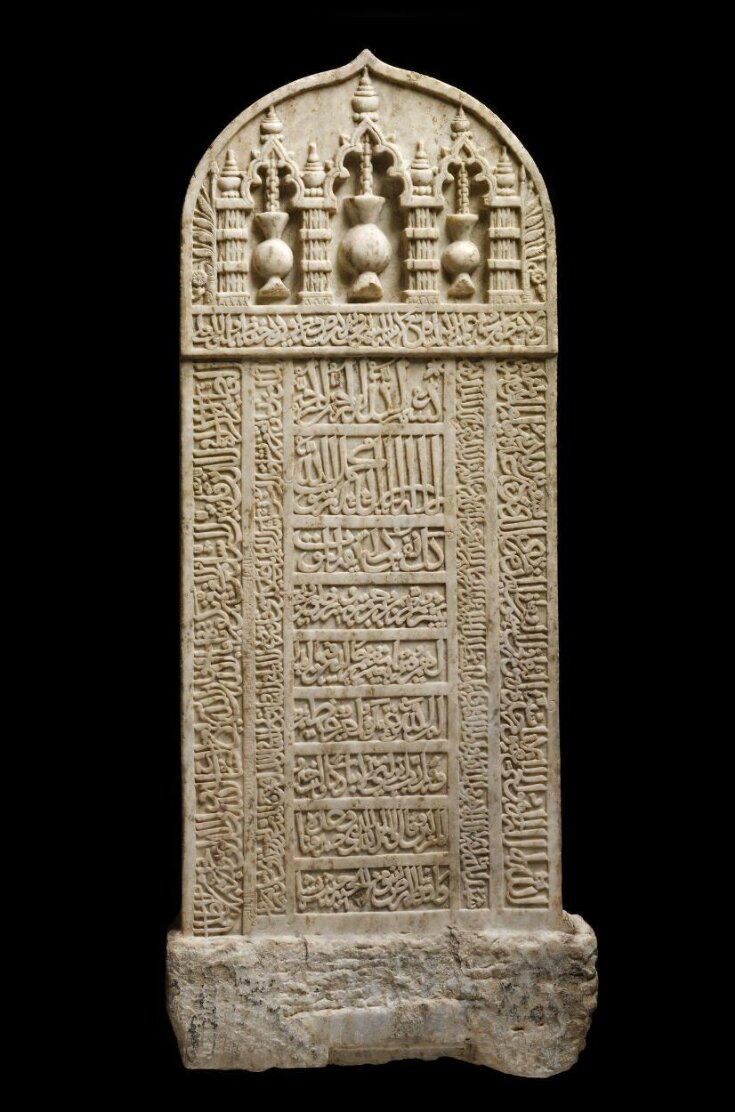

Tombstone of marble, carved in Khambhat, Gujarat, circa 1300-10 and shipped to Dhofar, now in Oman, where a section of the inscription was re-carved circa 1311. In its altered form, it was used with another, similar tombstone (V&A: A.13-1933) to mark the grave of the Rasulid governor of Dhofar, al-Malik al-Wathiq Nur al-Din Ibrahim. Unusually for a tombstone from this source, but like its pair, the stele is carved on both sides and around the edge, which is decorated with a formal vine-scroll motif. Both of the main faces have a tall, rectangular main section beneath an upper section in the form of a pointed arch. On one side this upper section projects slightly. It is carved in high relief with a row of three contiguous arches, each containing a hanging lamp, and with half a plantain or banana plant filling the space on either side. On the reverse, where the upper section is flush with the rest of the surface, a single arch frames a hanging lamp, with the same half-plant motifs on either side. The motif of a lamp hanging in an arch is more or less conventional for Khambhat tombstones of this period, and the same can be said of the layout of the inscriptions, the styles of script employed, and the calligraphic compositions (see Lambourn, Carving and Communities, and compare V&A: A.5-1932 and A.13-1933). The roughly cut base was meant to be concealed underground.

Inscriptions

On the side with the triple arch motif, a stack of nine horizontal bands of different heights fills the centre of the main section. It contains the basmalah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”; line 1), the shahādah (“There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God”; line 2) and a series of quotations from the Qur’an. These consist of a phrase from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 185, “Every soul shall taste death”; line 3); two verses from al-Tawbah (IX, 21-22; lines 4-6); and short quotations from al-Mu’minūn (XXIII, 29) and al-Zumar (XXXIX, 74, to حيث نشاء), run together (lines 7-9). A much longer quotation from the surah al-Baqarah (II) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, along the band at the base of the upper section and down the left side. This contains the Throne Verse (II, 255) and continues to يخرجهم من الظلمات in verse 257. Finally, the two narrower vertical bands within this framing inscription contain verses from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 18-19, to إنّ الدين عند الله الإسلام, and 26-7).

On the side with a single arch, another quotation from al-Baqarah (II, 285-6) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, around the arched top and down the left side. A second framing band runs up the narrow vertical band on the left, across the base of the upper section, beneath the arch and lamp, and down the narrow vertical band on the right. It is filled with a quotation from the surah al-Ḥashr (LIX), which runs from the beginning of verse 21 to الأسماء الحسنى in verse 24. These two framing inscriptions enclose a stack of six horizontal bands of different heights. The first two again contain the basmalah and the shahādah, which are part of the original decoration executed in Khambhat, while the remaining four were re-carved with the surah al-Fātiḥah (I, 2-7) at a slightly later date, and in a different style of calligraphy.

Styles of script

The main style of script employed is closely related to the expert chancery hands used in royal decrees and other official documents (compare Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy, Edinburgh, 2006, fig. 9.7). This is evident from the letter forms, e.g. the base of the letter alif (independent form) has an extension to the left, and the letter hā’ (final form) is written as a flourish rather than as a closed shape, but even more so from the use of the “hanging” (ta‘līq) arrangement of the text, in which groups of letters run diagonally, from top right to bottom left, within the space allocated to the line of text.

A second style of script was used for the basmalah and the shahādah inscriptions on both sides, which reflect standardized compositions. The letter forms in this style are very similar to those in the other inscriptions, with the addition of serifs to vertical strokes in many cases, but there is no ta‘līq stacking, as the scribe followed the horizontal base line in composing the text. The scale is larger, too: the band containing the shahādah is twice as tall as line 1, which is already taller than the rest. The vertical elements in the shahādah are therefore much taller, which is especially striking in the composition of the first phrase, “There is no god but God” (to the right in line 2). Emphasizing part of the text by creating a forest of parallel vertical strokes is a common practice in inscriptions from Khambhat and is itself reminiscent of the ṭughrā element in royal decrees, which contains the name and title of the sultan (again compare Blair, fig. 9.7).

The scribe in South Arabia who composed the surah al-Fātiḥah used many letter forms comparable to those carved in Khambhat, but other aspects of the inscription are reminiscent of earlier “broken cursive” styles (Déroche's New Style), e.g. the mannered rendition of the letter ‘ayn in line 3. The composition is more awkward, with more voids in the design, which are filled with decorative elements. The ornamental frame that surrounds each line of text marks this carving apart, and the inscription is recessed slightly compared to the rest. The likely explanation is that the original surface was chiselled away so that an earlier inscription, probably an epitaph, could be replaced with al-Fātiḥah (Lambourn, Carving and Recarving).

Inscriptions

On the side with the triple arch motif, a stack of nine horizontal bands of different heights fills the centre of the main section. It contains the basmalah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”; line 1), the shahādah (“There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God”; line 2) and a series of quotations from the Qur’an. These consist of a phrase from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 185, “Every soul shall taste death”; line 3); two verses from al-Tawbah (IX, 21-22; lines 4-6); and short quotations from al-Mu’minūn (XXIII, 29) and al-Zumar (XXXIX, 74, to حيث نشاء), run together (lines 7-9). A much longer quotation from the surah al-Baqarah (II) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, along the band at the base of the upper section and down the left side. This contains the Throne Verse (II, 255) and continues to يخرجهم من الظلمات in verse 257. Finally, the two narrower vertical bands within this framing inscription contain verses from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 18-19, to إنّ الدين عند الله الإسلام, and 26-7).

On the side with a single arch, another quotation from al-Baqarah (II, 285-6) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, around the arched top and down the left side. A second framing band runs up the narrow vertical band on the left, across the base of the upper section, beneath the arch and lamp, and down the narrow vertical band on the right. It is filled with a quotation from the surah al-Ḥashr (LIX), which runs from the beginning of verse 21 to الأسماء الحسنى in verse 24. These two framing inscriptions enclose a stack of six horizontal bands of different heights. The first two again contain the basmalah and the shahādah, which are part of the original decoration executed in Khambhat, while the remaining four were re-carved with the surah al-Fātiḥah (I, 2-7) at a slightly later date, and in a different style of calligraphy.

Styles of script

The main style of script employed is closely related to the expert chancery hands used in royal decrees and other official documents (compare Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy, Edinburgh, 2006, fig. 9.7). This is evident from the letter forms, e.g. the base of the letter alif (independent form) has an extension to the left, and the letter hā’ (final form) is written as a flourish rather than as a closed shape, but even more so from the use of the “hanging” (ta‘līq) arrangement of the text, in which groups of letters run diagonally, from top right to bottom left, within the space allocated to the line of text.

A second style of script was used for the basmalah and the shahādah inscriptions on both sides, which reflect standardized compositions. The letter forms in this style are very similar to those in the other inscriptions, with the addition of serifs to vertical strokes in many cases, but there is no ta‘līq stacking, as the scribe followed the horizontal base line in composing the text. The scale is larger, too: the band containing the shahādah is twice as tall as line 1, which is already taller than the rest. The vertical elements in the shahādah are therefore much taller, which is especially striking in the composition of the first phrase, “There is no god but God” (to the right in line 2). Emphasizing part of the text by creating a forest of parallel vertical strokes is a common practice in inscriptions from Khambhat and is itself reminiscent of the ṭughrā element in royal decrees, which contains the name and title of the sultan (again compare Blair, fig. 9.7).

The scribe in South Arabia who composed the surah al-Fātiḥah used many letter forms comparable to those carved in Khambhat, but other aspects of the inscription are reminiscent of earlier “broken cursive” styles (Déroche's New Style), e.g. the mannered rendition of the letter ‘ayn in line 3. The composition is more awkward, with more voids in the design, which are filled with decorative elements. The ornamental frame that surrounds each line of text marks this carving apart, and the inscription is recessed slightly compared to the rest. The likely explanation is that the original surface was chiselled away so that an earlier inscription, probably an epitaph, could be replaced with al-Fātiḥah (Lambourn, Carving and Recarving).

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Carved marble |

| Brief description | Tombstone of carved marble, Khambhat, Gujarat, circa 1300-10. |

| Physical description | Tombstone of marble, carved in Khambhat, Gujarat, circa 1300-10 and shipped to Dhofar, now in Oman, where a section of the inscription was re-carved circa 1311. In its altered form, it was used with another, similar tombstone (V&A: A.13-1933) to mark the grave of the Rasulid governor of Dhofar, al-Malik al-Wathiq Nur al-Din Ibrahim. Unusually for a tombstone from this source, but like its pair, the stele is carved on both sides and around the edge, which is decorated with a formal vine-scroll motif. Both of the main faces have a tall, rectangular main section beneath an upper section in the form of a pointed arch. On one side this upper section projects slightly. It is carved in high relief with a row of three contiguous arches, each containing a hanging lamp, and with half a plantain or banana plant filling the space on either side. On the reverse, where the upper section is flush with the rest of the surface, a single arch frames a hanging lamp, with the same half-plant motifs on either side. The motif of a lamp hanging in an arch is more or less conventional for Khambhat tombstones of this period, and the same can be said of the layout of the inscriptions, the styles of script employed, and the calligraphic compositions (see Lambourn, Carving and Communities, and compare V&A: A.5-1932 and A.13-1933). The roughly cut base was meant to be concealed underground. Inscriptions On the side with the triple arch motif, a stack of nine horizontal bands of different heights fills the centre of the main section. It contains the basmalah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”; line 1), the shahādah (“There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God”; line 2) and a series of quotations from the Qur’an. These consist of a phrase from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 185, “Every soul shall taste death”; line 3); two verses from al-Tawbah (IX, 21-22; lines 4-6); and short quotations from al-Mu’minūn (XXIII, 29) and al-Zumar (XXXIX, 74, to حيث نشاء), run together (lines 7-9). A much longer quotation from the surah al-Baqarah (II) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, along the band at the base of the upper section and down the left side. This contains the Throne Verse (II, 255) and continues to يخرجهم من الظلمات in verse 257. Finally, the two narrower vertical bands within this framing inscription contain verses from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 18-19, to إنّ الدين عند الله الإسلام, and 26-7). On the side with a single arch, another quotation from al-Baqarah (II, 285-6) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, around the arched top and down the left side. A second framing band runs up the narrow vertical band on the left, across the base of the upper section, beneath the arch and lamp, and down the narrow vertical band on the right. It is filled with a quotation from the surah al-Ḥashr (LIX), which runs from the beginning of verse 21 to الأسماء الحسنى in verse 24. These two framing inscriptions enclose a stack of six horizontal bands of different heights. The first two again contain the basmalah and the shahādah, which are part of the original decoration executed in Khambhat, while the remaining four were re-carved with the surah al-Fātiḥah (I, 2-7) at a slightly later date, and in a different style of calligraphy. Styles of script The main style of script employed is closely related to the expert chancery hands used in royal decrees and other official documents (compare Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy, Edinburgh, 2006, fig. 9.7). This is evident from the letter forms, e.g. the base of the letter alif (independent form) has an extension to the left, and the letter hā’ (final form) is written as a flourish rather than as a closed shape, but even more so from the use of the “hanging” (ta‘līq) arrangement of the text, in which groups of letters run diagonally, from top right to bottom left, within the space allocated to the line of text. A second style of script was used for the basmalah and the shahādah inscriptions on both sides, which reflect standardized compositions. The letter forms in this style are very similar to those in the other inscriptions, with the addition of serifs to vertical strokes in many cases, but there is no ta‘līq stacking, as the scribe followed the horizontal base line in composing the text. The scale is larger, too: the band containing the shahādah is twice as tall as line 1, which is already taller than the rest. The vertical elements in the shahādah are therefore much taller, which is especially striking in the composition of the first phrase, “There is no god but God” (to the right in line 2). Emphasizing part of the text by creating a forest of parallel vertical strokes is a common practice in inscriptions from Khambhat and is itself reminiscent of the ṭughrā element in royal decrees, which contains the name and title of the sultan (again compare Blair, fig. 9.7). The scribe in South Arabia who composed the surah al-Fātiḥah used many letter forms comparable to those carved in Khambhat, but other aspects of the inscription are reminiscent of earlier “broken cursive” styles (Déroche's New Style), e.g. the mannered rendition of the letter ‘ayn in line 3. The composition is more awkward, with more voids in the design, which are filled with decorative elements. The ornamental frame that surrounds each line of text marks this carving apart, and the inscription is recessed slightly compared to the rest. The likely explanation is that the original surface was chiselled away so that an earlier inscription, probably an epitaph, could be replaced with al-Fātiḥah (Lambourn, Carving and Recarving). |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | This tombstone is part of a production in Khambhat (Cambay) in Gujarat that supplied a market for Muslim grave-markers around the Indian Ocean, from East Africa to South East Asia (see Lambourn, Carving and Communities). It is a rare (and presumably more expensive) example as it was carved on both faces. This tombstone now forms a pair with V&A: A.13-1933, being the headstone and footstone from the grave of al-Malik al-Wathiq Nur al-Din Ibrahim ibn al-Malik al-Muzaffar (d. 1311), a member of the Rasulid dynasty who was governor of the province of Dhofar from 1292 until his death. His residence was in the city of Zafar (ظفار), which gave its name to the province and which is now the archaeological site of al-Balid near the modern capital of Salalah. Nevertheless, both tombstones were almost certainly commissioned by other inhabitants of Zafar. Their identities have been lost, as their epitaphs were erased when the stones were re-purposed for the governor's grave (see Lambourn, Carving and Recarving). This stone and V&A: A.13-1933 were acquired from Squadron Leader Aubrey R.M. Rickards of the Royal Air Force in May 1933 at the price of £40. The purchase was approved at the time by the Lords Commissioners of H.M. Treasury and the Air Ministry. Rickards (1898–1937) served in what became the Royal Air Force, from 1917 to 1937; in that year he was killed with two colleagues when their plane crashed at Khor Gharim on the south coast of Oman. He had served in the Middle East from 1918, flying between the Aden Protectorate, the Gulf and Iraq, and he is recorded as active in the Dhofar region of Oman in 1929 and 1930. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.12-1933 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 25, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest