Pattern Book

1816-1826 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

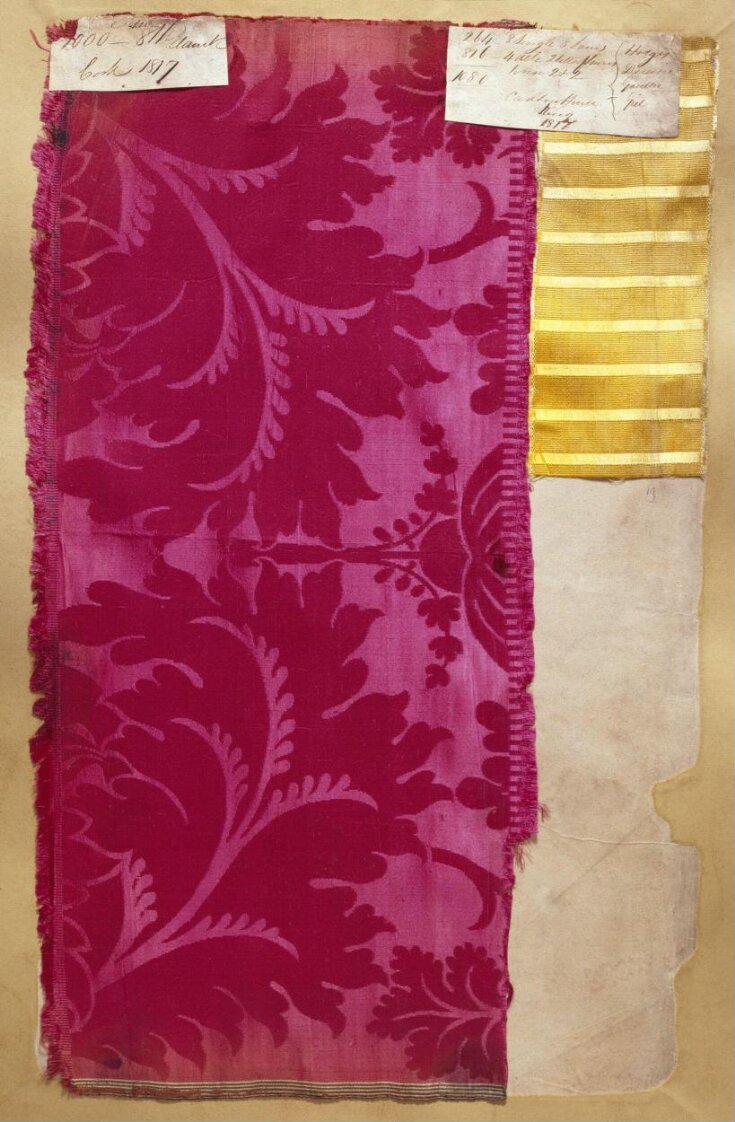

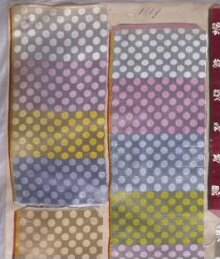

Documenting the weaving business of Jourdain & John Ham from 1816 until 1826, this volume gives an insight into technical innovation in Spitalfields. With fashion demanding small patterns, the samples include many called ‘colour blankets’, which show a single pattern worked into a background banded in differing tones. Woven across are diverse shades of silk. Typically using six tones in the vertical direction (the warp) on a cloth approximately 21 inches wide, the result was cut into variously-coloured strips each about 3.5 inches wide. None of these cloths were intended to be sold “as is”. Instead the mercer would order one specific colour.

Although the patterns are small, many are too complex for a standard shaft loom. One example positions some 70 separate horizontal threads (wefts), detail beyond the capacity of a shaft loom. The drawloom, used in Spitalfields for the elaborate 18th century brocades, could provide such precision. However, it was time-consuming to set up and thus uneconomical for such petite patterns. The solution was a device set on the floor beside the loom, replacing the second person – or draw boy – needed to work a drawloom. This mechanism used pegs set into a cylinder to draw down selected cords that in turn lifted the appropriate warp threads.

Perfected in c1805 by Alexander Duff, it was illustrated as ‘Duff's draw boy’ in Abraham Rees' Cyclopedia or Universal Dictionary, published in London in 1819. However, in 1810 John Sholl was awarded a Royal Society of Arts (RSA) prize of 15 guineas for improvements to this mechanism. Supporting his prize was testimony from several Spitalfields’ master weavers, including Lea, Wilson & Co. Sholl, they stated, had worked for them for many years and his improved machine produced cloths ‘hitherto thought impossible...without the assistance of a second workman.’ Entirely forgotten in recent years, this innovation contributed to the technical properties of several later types of looms and was highlighted in a 1912 edition of the RSA Journal, where it was called a ‘mechanical drawboy.’

It was especially useful for making more complex offerings, with “squared” cloths showing different patterns in each horizontal band. (p.24) Called ‘pattern blankets’, their introduction contributed to both the expansion of London silk weaving and complex debates about wages. Weavers were paid for completed cloths at rates set by the Spitalfields Acts (instituted in 1773). More elaborate cloths attracted a higher wage, part going to the draw boy. Once eliminated, some wished to reduce wages. Eventually the Acts were repealed in 1824, as was the 1776 Act forbidding the importation of French silks. Both changes took effect in 1826. By then the Jacquard loom, patented in 1820 by Stephen Wilson, had begun its slow journey towards replacing the mechanical drawboy.

Author: Mary Schoeser, Honorary Senior Research Fellow, VARI, 2023

Although the patterns are small, many are too complex for a standard shaft loom. One example positions some 70 separate horizontal threads (wefts), detail beyond the capacity of a shaft loom. The drawloom, used in Spitalfields for the elaborate 18th century brocades, could provide such precision. However, it was time-consuming to set up and thus uneconomical for such petite patterns. The solution was a device set on the floor beside the loom, replacing the second person – or draw boy – needed to work a drawloom. This mechanism used pegs set into a cylinder to draw down selected cords that in turn lifted the appropriate warp threads.

Perfected in c1805 by Alexander Duff, it was illustrated as ‘Duff's draw boy’ in Abraham Rees' Cyclopedia or Universal Dictionary, published in London in 1819. However, in 1810 John Sholl was awarded a Royal Society of Arts (RSA) prize of 15 guineas for improvements to this mechanism. Supporting his prize was testimony from several Spitalfields’ master weavers, including Lea, Wilson & Co. Sholl, they stated, had worked for them for many years and his improved machine produced cloths ‘hitherto thought impossible...without the assistance of a second workman.’ Entirely forgotten in recent years, this innovation contributed to the technical properties of several later types of looms and was highlighted in a 1912 edition of the RSA Journal, where it was called a ‘mechanical drawboy.’

It was especially useful for making more complex offerings, with “squared” cloths showing different patterns in each horizontal band. (p.24) Called ‘pattern blankets’, their introduction contributed to both the expansion of London silk weaving and complex debates about wages. Weavers were paid for completed cloths at rates set by the Spitalfields Acts (instituted in 1773). More elaborate cloths attracted a higher wage, part going to the draw boy. Once eliminated, some wished to reduce wages. Eventually the Acts were repealed in 1824, as was the 1776 Act forbidding the importation of French silks. Both changes took effect in 1826. By then the Jacquard loom, patented in 1820 by Stephen Wilson, had begun its slow journey towards replacing the mechanical drawboy.

Author: Mary Schoeser, Honorary Senior Research Fellow, VARI, 2023

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 143 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | |

| Brief description | Pattern book, British, 1816-1826, silk samples |

| Physical description | Pattern book containing samples of woven silks in various colours. The samples include velvet, gauze, satins, twills, cecks, ribs, taffetas, and furnishing damasks |

| Dimensions |

|

| Summary | Documenting the weaving business of Jourdain & John Ham from 1816 until 1826, this volume gives an insight into technical innovation in Spitalfields. With fashion demanding small patterns, the samples include many called ‘colour blankets’, which show a single pattern worked into a background banded in differing tones. Woven across are diverse shades of silk. Typically using six tones in the vertical direction (the warp) on a cloth approximately 21 inches wide, the result was cut into variously-coloured strips each about 3.5 inches wide. None of these cloths were intended to be sold “as is”. Instead the mercer would order one specific colour. Although the patterns are small, many are too complex for a standard shaft loom. One example positions some 70 separate horizontal threads (wefts), detail beyond the capacity of a shaft loom. The drawloom, used in Spitalfields for the elaborate 18th century brocades, could provide such precision. However, it was time-consuming to set up and thus uneconomical for such petite patterns. The solution was a device set on the floor beside the loom, replacing the second person – or draw boy – needed to work a drawloom. This mechanism used pegs set into a cylinder to draw down selected cords that in turn lifted the appropriate warp threads. Perfected in c1805 by Alexander Duff, it was illustrated as ‘Duff's draw boy’ in Abraham Rees' Cyclopedia or Universal Dictionary, published in London in 1819. However, in 1810 John Sholl was awarded a Royal Society of Arts (RSA) prize of 15 guineas for improvements to this mechanism. Supporting his prize was testimony from several Spitalfields’ master weavers, including Lea, Wilson & Co. Sholl, they stated, had worked for them for many years and his improved machine produced cloths ‘hitherto thought impossible...without the assistance of a second workman.’ Entirely forgotten in recent years, this innovation contributed to the technical properties of several later types of looms and was highlighted in a 1912 edition of the RSA Journal, where it was called a ‘mechanical drawboy.’ It was especially useful for making more complex offerings, with “squared” cloths showing different patterns in each horizontal band. (p.24) Called ‘pattern blankets’, their introduction contributed to both the expansion of London silk weaving and complex debates about wages. Weavers were paid for completed cloths at rates set by the Spitalfields Acts (instituted in 1773). More elaborate cloths attracted a higher wage, part going to the draw boy. Once eliminated, some wished to reduce wages. Eventually the Acts were repealed in 1824, as was the 1776 Act forbidding the importation of French silks. Both changes took effect in 1826. By then the Jacquard loom, patented in 1820 by Stephen Wilson, had begun its slow journey towards replacing the mechanical drawboy. Author: Mary Schoeser, Honorary Senior Research Fellow, VARI, 2023 |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | T.385:65-1972 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | May 10, 2000 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest