Misericord

late 14th century (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Misericords were set on the underside of the hinged seats in the choirs of churches. They had no religious function but gave some support to the monks and clergy in the long parts of the services when standing was required. This explains the name 'misericord', which comes from the Latin for mercy. The decoration was often amusing, sometimes moral, and included grotesque figures and observations of the natural world in depictions of animals, birds and foliage.

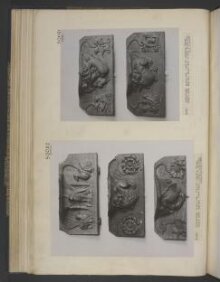

This misericord is decorated with a carving of an eagle holding a blank scroll in its beak. An eagle is the attribute of St. John the Evangelist, and the carving may have been intended to be a representation of this.

This misericord was probably carved in East Anglia, but we do not know which church it came from.

This misericord is decorated with a carving of an eagle holding a blank scroll in its beak. An eagle is the attribute of St. John the Evangelist, and the carving may have been intended to be a representation of this.

This misericord was probably carved in East Anglia, but we do not know which church it came from.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | carved oak |

| Brief description | English, 1380-1400, oak, 95/1698, 62/1698 |

| Physical description | Made of a solid, rectangular (landscape) piece of oak. The two top corners of the seat are cut away to form a concave curve at each corner. A hinge of approximately 4cm width occurs near either end of the lower edge of the seat. The misericord itself is bordered with a six-sided double moulding with a tapering and faceted support to the bracket below. Obscuring most of this bracket is a carved eagle, with outstretched wings and blank scroll in its beak which unfurls to its claws. At either side of the eagle is a supporter, which extends out from the ledge as a curved branch ending in two creatures, both wearing a cloak-like garment or surplice which covers most of their lower half. The creature on the right appears to be some sort of wingless bird, with a long beak. The mammal-like figure on the left has a rounded mouth and large eyes. Both creatures face inward toward the eagle. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | This misericord is one of ten (W.6 to 12 and 52 to 54-1921) which were purchased by the V&A from the Architectural Association (34 & 35 Bedford Square, WC1), per Messrs Bricciani & Co. 254 Goswell Road, EC1., in 1921. The group was purchased in 1921 as part of a larger acquisition of fifty-eight pieces of woodwork for £500. It was originally assumed that all ten misericords were from St Nicholas Chapel, Kings Lynn until G.L. Remnant – in A Catalogue of Misericords in Great Britain , Oxford, 1969 – pointed out the differences in design in the seats. It is now thought the misericords divide into two groups: one of six (W.6,9 to 12 and 54-1921), which are still believed to be from St Nicholas and one of four (W.7,8,52 and 53-1921) which, while possibly still from East Anglia, are not now thought to be from St Nicholas. This misericord is one of the four not thought to come from St Nicholas. |

| Historical context | Misericord is the name given to the ledge supported by a corbel which is revealed when the hinged seats in medieval choir stalls are tipped up. The word comes from the Latin misericordia which means pity and alludes to the original function of the ledge. The rule of St Benedict, introduced in the sixth century AD, required the monks to sing the eight daily offices of the Church (Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers and Compline) standing up. They were only permitted to sit during the Epistle and Gradual at Mass and the Response at Vespers. Such long hours spent standing was particularly arduous for the older and weaker monks and they soon adopted a leaning staff or crutch to help take the weight off their feet. By the eleventh century the rules were slightly relaxed and misericords were introduced – the monks were able to perch on the ledge and lean back slightly, taking much of the weight off their feet whilst still giving the appearance of standing up straight. They were in use wherever the monks were required to sing the daily offices, including cathedrals, abbeys and collegiate churches. They sometimes even appeared in Parish churches. The earliest mention of misericords appears in the eleventh century in the rules of the monastery of Hirsau in Germany. It is not known when they were introduced in Britain but the earliest surviving examples are found at Hemingbrough in North Yorkshire and Christchurch in Dorset. Both date from the early thirteenth century. The earliest complete set of misericords is in Exeter Cathedral and dates from 1240 to 1270. The choir seat, the ledge and the corbel supporting it were made of a single piece of wood, usually oak. The corbel provided an ideal platform for medieval craftsmen to carve all manner of narrative scenes and decoration. British misericords differ from those elsewhere in Europe by having subsidiary carvings on either side of the central corbel. These are known as supporters and are often used to develop the theme introduced in the carving of the corbel. Over half of the misericords in Britain are decorated with foliage but of those which do have narrative decoration, both in Britain and on the Continent, very few depict religious subjects. More common themes included scenes of everyday life and moral tales, often being depicted in a humerous way. Whether, as has been suggested, the lack of religious scenes was because the hidden location of the misericords meant craftsmen were more free to be creative with their carving, or whether the monks would have thought it inappropriate to sit on images of Christ, Saints or biblical scenes is not known. However, their lack of overt religious content together with their concealed physical position probably contributed to a large number of them surviving the Reformation and still existing today. Information taken mainly from: Church Misericords and Bench Ends, Richard Hayman, Shire Publications, Buckinghamshire, 1989 (no copy in the NAL) The World Upside-Down – English Misericords, Christa Grössinger, London, 1997 (NAL = 273.H.95) |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Misericords were set on the underside of the hinged seats in the choirs of churches. They had no religious function but gave some support to the monks and clergy in the long parts of the services when standing was required. This explains the name 'misericord', which comes from the Latin for mercy. The decoration was often amusing, sometimes moral, and included grotesque figures and observations of the natural world in depictions of animals, birds and foliage. This misericord is decorated with a carving of an eagle holding a blank scroll in its beak. An eagle is the attribute of St. John the Evangelist, and the carving may have been intended to be a representation of this. This misericord was probably carved in East Anglia, but we do not know which church it came from. |

| Associated objects | |

| Bibliographic reference | Charles Tracy, English Medieval Furniture and Woodwork (London, 1988), cat. no. 71.

Misericord, one of four (W.7-1921, W.8-1921, W.52-1921, W.53-1921) the seats, bordered with a six-sided double moulding with a tapering and facetted support to the bracket (PLs 21-24); below are carved three harvesting scenes — stooking (W.8-1921), carting (W.53-1921) and threshing the corn (W.7-1921), and the image of an eagle with a scroll in its beak, flanked on either side by grotesque figures (W.52-1921).

Probably from East Anglia

Oak. Late 14th century

29.2 X 56 X 15.3 cm

Mus no. W.52-1921

These misericords were purchased, with the six below (Mus Nos. W.6-1921, W.9-1921,W.10-1921, W.11-1921,W.12-1921, W54-1921) from the Royal Architectural Museum, Westminster. It had been assumed that all ten misericords were from St Nicholas, King's Lynn until Remnant (G.L. Remnant (with an introduction by L.M.D. Anderson), A Catalogue of Misericords in Great Britain, Oxford, 1969.p. 94) pointed out the differences in design in the seats. These carvings must, indeed, come from a different, and unidentified set of choir-stalls.

The harvesting scenes were probably associated with a cycle of the labours of the month and copied from calendar illustrations. Such cycles are likely to have been common but, unfortunately, all that is left is a few individual misericords. All three of the subjects displayed on the museum's carvings are unique. Considering the popularity of these cycles in manuscript illumination, it is surprising that there are only six examples in England of the cutting of corn on misericords (FIG.17).

Of equal interest in this set of carvings is the treatment of the supporters. There are a pair of pygmies, two pairs of half-humans, half-animals and a pair of so-called blemyae. The latter are from the repertory of fantastic creatures mentioned by Pliny in Natural History and later in books such as Mandeville's Travels written in French about 1357. The blemya or anthropopaghus was a man with no head and a face in his chest. He is described in a fifteenth century translation of Mandeville's Travels: ’And in another yle also ben folk that han non hedes, and here eyen and here mouth ben behynde in here schuldres’ (M.C. Seymour, MandeviIIe’s Travels, Oxford, 1967.p.147). Those illustrated in the Livre de Merveilles (Bib.Nat.ancien fonds francais 2816), a collection of accounts of the Orient which includes Mandeville, show how these men were usually presented. The pair on the misericord of the thresher seem to be a conflation of blemya and pygmy. The more conventional treatment can be seen on the late fifteenth-century examples at Norwich (FIG.18) and Ripon cathedrals.

These four misericords are quite distinct from the group of six seats from St Nicholas King's Lynn (see Mus.Nos. W.6-1921, W.9-1921,W.10-1921, W.11-1921,W.12-1921, W54-1921) church. They could be from East Anglia but they are probably slightly earlier in date than the King’s Lynn furniture, that is, of the late fourteenth century. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.52-1921 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 24, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest