Blotter

ca. 1906-14 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Writing culture and blotting

Educational reforms meant that writing became much more widespread in the United Kingdom during the nineteenth century, while factors including technological advances and extensive railway systems contributed to the development of a thriving consumer culture. As a result, there was a growing market for products connected to writing. Examples include paper clips, paper knives, letter racks and various forms of blotting equipment. Similar shifts took place outside of the United Kingdom in places including France and the United States.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century people in the United Kingdom and elsewhere typically dealt with wet ink on glazed paper by applying a product called pounce (usually powdered chalk, sometimes biotite [powdered magnesia mica]) as a drying agent. But by the 1840s blotting paper had taken over from pounce. Accounts of something similar to blotting paper date back to late medieval times, and there is evidence to show that such paper was being used from the eighteenth century, but it is thought that the product began to be produced commercially in the United Kingdom from the 1840s following a mistake at East Hagbourne Mill, Berkshire, England; while producing paper, employees are said to have forgotten to add size to the mixture. The end product was absorbent paper initially viewed as waste but subsequently recognised as useful for taking up wet ink. East Hagbourne Mill, then run by John Slade, successfully produced and sold ‘Slade’s Original Hand Made Blotting’, which soon became known as ‘Ford’s Blotting’ following a change of ownership.

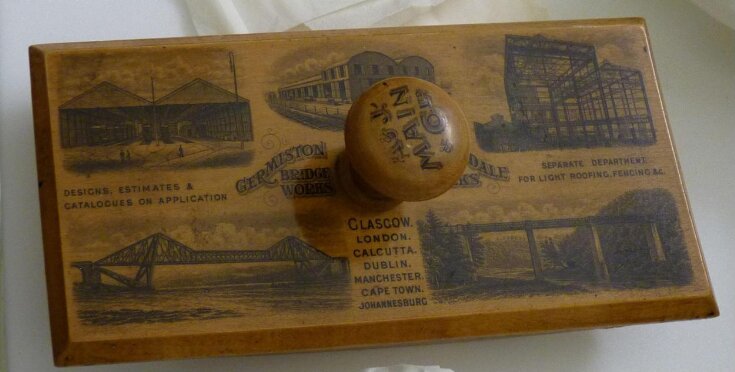

Blotting paper came to be associated with a range of accessories including the rocker blotter. These blotters were made of materials including wood and metal and typically consisted of three separable parts: a handle; a flat, rectangular part; and a piece with a curved underside. The paper was placed against the curved edge, pressed between the curved and flat elements, and secured in place by the handle when it was screwed through the parts below. This particular blotter was acquired with an old piece of blotting paper secured into position.

Rocker blotters were decorated in a range of ways, including using Mauchline Ware techniques.

Mauchline Ware

Mauchline Ware has also been referred to by names including ‘Scottish white wood production’ and ‘Scottish fancy goods’. Its three most characteristic features are the wood used, the finishes applied and the final varnishing process. Almost all Mauchline Ware is made from plane, also known as sycamore. Features of this wood that make it suitable for decorative goods include lack of knots, close texture and resistance to warping. The six most common finishes of Mauchline Ware have been described by David Trachtenberg and Thomas Keith (Mauchline Ware: A Collector's Guide) as Transfer, Tartan, Fern, Photographic, Black Lacquer and Victorian Illustration. Numerous coats of durable copal varnish (tree resin) provide protection and maintain the pale colour of the plane on pieces where the wood is not fully covered by a decorative finish.

Mauchline Ware was widely produced in Mauchline but also Ayrshire, Scotland more broadly by the mid-1840s. At the start of the century the county had been a major producer of snuff boxes made from plane and hand-decorated with paint or pen and ink. It is thought that the wood was usually sourced locally. As snuff (powdered tobacco) went out of fashion in the 1820s, and as the demand for souvenirs rose with the expansion of the railways, the industry needed to evolve. Many companies started to produce a range of small goods in a variety of finishes, the dominant one being Transfer, which was suitable for souvenirs because it could easily depict places. Scottish manufacturers are thought to have purchased engraved plates depicting a range of places and to have exported widely to the areas depicted on their products.

The Transfer technique was an attempt to replicate the labour-intensive process of hand-drawing pen and ink pictures, known as ‘washes’. At the start of the Transfer process the item was coated in two or three layers of shellac (insect resin dissolved in alcohol). A print of an engraving was made on a special kind of paper which was varnished and placed on the object ink side down and left to dry for a couple of hours. The print was wetted and the paper, durable but fine enough to be sponged away, was rubbed off. Finally, up to twelve coats of durable copal varnish were applied, a process that could take up to twelve weeks.

It is not known precisely when and where the Transfer method was first used. Earlier in the nineteenth century Johann Georg Hiltl and his son Anton Hiltl were using this method in modern day Germany, then Bavaria (see V&A W.9:1 to 2-1965). But certainly it was widely used in Ayrshire from the mid-1840s, where it was likely introduced by the Smiths of Mauchline. This family business was established in 1810. Initially the company specialised in a few areas including snuff boxes, but it soon expanded its offering and methods and came to dominate the Mauchline Ware market, which reached its zenith between 1860 and 1900. Mauchline Ware continued to be made until the 1930s. A fire at the Smiths’ last factory in 1933 effectively ended production and the factory closed in 1939. This last factory was in Mauchline, but the Smiths also operated in Birmingham, England, apparently from around the late 1820s until 1904. Similar goods are known to have been made in Germany when this style had its heyday. Such pieces were often marked ‘Made in Germany’ from the late 1880s in line with the Merchandise Marks Act 1887.

This blotter (CIRC.406-1975)

The Smiths may have produced this blotter. The name of the manufacturer does not appear to be given on the item itself, but companies rarely applied their names to Mauchline Ware, except for their own promotional pieces. Relatedly, Mauchline Ware was often used for advertising as well as souvenirs, particularly by cotton thread companies. It is thought that such goods were often giveaways, gifts to loyal or prospective customers. This blotter in the V&A collection advertises A. & J. Main & Co. Ltd, ironmongers established in the later 1860s in Glasgow, Scotland.

The blotter appears to have been made between around 1906 to 1914. It cannot have been produced at a much earlier date because it was during or around 1906 that A. & J. Main acquired Arrol Bridge & Roof Co.’s Germiston Works in Glasgow, which is referenced on the blotter. The blotter is not likely to have been made during World War I (1914 to 1918) and the style of the lettering, particularly that used for the company name, suggests an earlier date. 1919 to 1922 can also be ruled out as the company went by Armstrongs and Main during this period. Further, Mauchline Ware ceased to be produced in the 1930s and A. & J. Main closed down in 1968.

The structures depicted were selected to advertise A. & J. Main’s ironwork business. Some of the scenes may be generic designs like most of the illustrations in A. & J. Main catalogues. Such designs might already have been held by the company that produced the blotter. It is more likely that A. & J. Main commissioned them. The Smiths are known to have made items to order. At least one of the vignettes, the bridge on the proper right of the blotter, depicted a real structure: Connel Ferry Bridge, constructed in 1903 as a railway bridge crossing Loch Etive in Scotland (the bridge is now used as a road and called Connel Bridge). Although A. & J. Main were not responsible for the construction of this bridge, by the time the company commissioned this blotter they had taken over Arrol Bridge & Roof Co. who had recently built Connel Ferry Bridge. It was common for advertising Mauchline Ware to depict places with which companies were associated, as demonstrated by a needlecase in the V&A collection that features Ballochmyle Creamery in Mauchline where ‘Seafoam’ (said to be the first margarine made using vegetable, rather than animal, fats) was made from the late nineteenth century (CIRC.425&A-1975). As indicated by products including this needlecase, Mauchline Ware almost always states the name of the place depicted below the image, but such information is not provided on this blotter. The places referenced on the object indicate A. & J. Main’s international reach.

Educational reforms meant that writing became much more widespread in the United Kingdom during the nineteenth century, while factors including technological advances and extensive railway systems contributed to the development of a thriving consumer culture. As a result, there was a growing market for products connected to writing. Examples include paper clips, paper knives, letter racks and various forms of blotting equipment. Similar shifts took place outside of the United Kingdom in places including France and the United States.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century people in the United Kingdom and elsewhere typically dealt with wet ink on glazed paper by applying a product called pounce (usually powdered chalk, sometimes biotite [powdered magnesia mica]) as a drying agent. But by the 1840s blotting paper had taken over from pounce. Accounts of something similar to blotting paper date back to late medieval times, and there is evidence to show that such paper was being used from the eighteenth century, but it is thought that the product began to be produced commercially in the United Kingdom from the 1840s following a mistake at East Hagbourne Mill, Berkshire, England; while producing paper, employees are said to have forgotten to add size to the mixture. The end product was absorbent paper initially viewed as waste but subsequently recognised as useful for taking up wet ink. East Hagbourne Mill, then run by John Slade, successfully produced and sold ‘Slade’s Original Hand Made Blotting’, which soon became known as ‘Ford’s Blotting’ following a change of ownership.

Blotting paper came to be associated with a range of accessories including the rocker blotter. These blotters were made of materials including wood and metal and typically consisted of three separable parts: a handle; a flat, rectangular part; and a piece with a curved underside. The paper was placed against the curved edge, pressed between the curved and flat elements, and secured in place by the handle when it was screwed through the parts below. This particular blotter was acquired with an old piece of blotting paper secured into position.

Rocker blotters were decorated in a range of ways, including using Mauchline Ware techniques.

Mauchline Ware

Mauchline Ware has also been referred to by names including ‘Scottish white wood production’ and ‘Scottish fancy goods’. Its three most characteristic features are the wood used, the finishes applied and the final varnishing process. Almost all Mauchline Ware is made from plane, also known as sycamore. Features of this wood that make it suitable for decorative goods include lack of knots, close texture and resistance to warping. The six most common finishes of Mauchline Ware have been described by David Trachtenberg and Thomas Keith (Mauchline Ware: A Collector's Guide) as Transfer, Tartan, Fern, Photographic, Black Lacquer and Victorian Illustration. Numerous coats of durable copal varnish (tree resin) provide protection and maintain the pale colour of the plane on pieces where the wood is not fully covered by a decorative finish.

Mauchline Ware was widely produced in Mauchline but also Ayrshire, Scotland more broadly by the mid-1840s. At the start of the century the county had been a major producer of snuff boxes made from plane and hand-decorated with paint or pen and ink. It is thought that the wood was usually sourced locally. As snuff (powdered tobacco) went out of fashion in the 1820s, and as the demand for souvenirs rose with the expansion of the railways, the industry needed to evolve. Many companies started to produce a range of small goods in a variety of finishes, the dominant one being Transfer, which was suitable for souvenirs because it could easily depict places. Scottish manufacturers are thought to have purchased engraved plates depicting a range of places and to have exported widely to the areas depicted on their products.

The Transfer technique was an attempt to replicate the labour-intensive process of hand-drawing pen and ink pictures, known as ‘washes’. At the start of the Transfer process the item was coated in two or three layers of shellac (insect resin dissolved in alcohol). A print of an engraving was made on a special kind of paper which was varnished and placed on the object ink side down and left to dry for a couple of hours. The print was wetted and the paper, durable but fine enough to be sponged away, was rubbed off. Finally, up to twelve coats of durable copal varnish were applied, a process that could take up to twelve weeks.

It is not known precisely when and where the Transfer method was first used. Earlier in the nineteenth century Johann Georg Hiltl and his son Anton Hiltl were using this method in modern day Germany, then Bavaria (see V&A W.9:1 to 2-1965). But certainly it was widely used in Ayrshire from the mid-1840s, where it was likely introduced by the Smiths of Mauchline. This family business was established in 1810. Initially the company specialised in a few areas including snuff boxes, but it soon expanded its offering and methods and came to dominate the Mauchline Ware market, which reached its zenith between 1860 and 1900. Mauchline Ware continued to be made until the 1930s. A fire at the Smiths’ last factory in 1933 effectively ended production and the factory closed in 1939. This last factory was in Mauchline, but the Smiths also operated in Birmingham, England, apparently from around the late 1820s until 1904. Similar goods are known to have been made in Germany when this style had its heyday. Such pieces were often marked ‘Made in Germany’ from the late 1880s in line with the Merchandise Marks Act 1887.

This blotter (CIRC.406-1975)

The Smiths may have produced this blotter. The name of the manufacturer does not appear to be given on the item itself, but companies rarely applied their names to Mauchline Ware, except for their own promotional pieces. Relatedly, Mauchline Ware was often used for advertising as well as souvenirs, particularly by cotton thread companies. It is thought that such goods were often giveaways, gifts to loyal or prospective customers. This blotter in the V&A collection advertises A. & J. Main & Co. Ltd, ironmongers established in the later 1860s in Glasgow, Scotland.

The blotter appears to have been made between around 1906 to 1914. It cannot have been produced at a much earlier date because it was during or around 1906 that A. & J. Main acquired Arrol Bridge & Roof Co.’s Germiston Works in Glasgow, which is referenced on the blotter. The blotter is not likely to have been made during World War I (1914 to 1918) and the style of the lettering, particularly that used for the company name, suggests an earlier date. 1919 to 1922 can also be ruled out as the company went by Armstrongs and Main during this period. Further, Mauchline Ware ceased to be produced in the 1930s and A. & J. Main closed down in 1968.

The structures depicted were selected to advertise A. & J. Main’s ironwork business. Some of the scenes may be generic designs like most of the illustrations in A. & J. Main catalogues. Such designs might already have been held by the company that produced the blotter. It is more likely that A. & J. Main commissioned them. The Smiths are known to have made items to order. At least one of the vignettes, the bridge on the proper right of the blotter, depicted a real structure: Connel Ferry Bridge, constructed in 1903 as a railway bridge crossing Loch Etive in Scotland (the bridge is now used as a road and called Connel Bridge). Although A. & J. Main were not responsible for the construction of this bridge, by the time the company commissioned this blotter they had taken over Arrol Bridge & Roof Co. who had recently built Connel Ferry Bridge. It was common for advertising Mauchline Ware to depict places with which companies were associated, as demonstrated by a needlecase in the V&A collection that features Ballochmyle Creamery in Mauchline where ‘Seafoam’ (said to be the first margarine made using vegetable, rather than animal, fats) was made from the late nineteenth century (CIRC.425&A-1975). As indicated by products including this needlecase, Mauchline Ware almost always states the name of the place depicted below the image, but such information is not provided on this blotter. The places referenced on the object indicate A. & J. Main’s international reach.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Probably plane, also known as sycamore, shellac, copal varnish, Mauchline Ware, Transfer method |

| Brief description | Blotter advertising A. & J. Main & Co. Ltd., possibly made by Smiths of Mauchline, probably made in Mauchline, Scotland, ca. 1906-14 |

| Physical description | Rocker blotter advertising A. & J. Main & Co. Ltd. Probably made of plane, also known as sycamore. Decorated with text and scenes applied using the Transfer Mauchline Ware method. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Handle: ‘A. & J. / MAIN / & CO. LTD.’

Top of blotter, proper right of handle: ‘GERMISTON / BRIDGE WORKS’

Top of blotter, proper left of handle: ‘CLYDESDALE / IRON WORKS’

Top of blotter, below handle: ‘GLASGOW. / LONDON. / CALCUTTA. / DUBLIN. / MANCHESTER. / CAPE TOWN. / JOHANNESBURG.’

Top of blotter, proper right: ‘DESIGNS, ESTIMATES & / CATALOGUES ON APPLICATION’

Top of blotter, proper left: ‘SEPARATE DEPARTMENT / FOR LIGHT ROOFING, FENCING &c.’

Two sides: ‘A. & J. MAIN & CO. LTD.’ |

| Summary | Writing culture and blotting Educational reforms meant that writing became much more widespread in the United Kingdom during the nineteenth century, while factors including technological advances and extensive railway systems contributed to the development of a thriving consumer culture. As a result, there was a growing market for products connected to writing. Examples include paper clips, paper knives, letter racks and various forms of blotting equipment. Similar shifts took place outside of the United Kingdom in places including France and the United States. In the early decades of the nineteenth century people in the United Kingdom and elsewhere typically dealt with wet ink on glazed paper by applying a product called pounce (usually powdered chalk, sometimes biotite [powdered magnesia mica]) as a drying agent. But by the 1840s blotting paper had taken over from pounce. Accounts of something similar to blotting paper date back to late medieval times, and there is evidence to show that such paper was being used from the eighteenth century, but it is thought that the product began to be produced commercially in the United Kingdom from the 1840s following a mistake at East Hagbourne Mill, Berkshire, England; while producing paper, employees are said to have forgotten to add size to the mixture. The end product was absorbent paper initially viewed as waste but subsequently recognised as useful for taking up wet ink. East Hagbourne Mill, then run by John Slade, successfully produced and sold ‘Slade’s Original Hand Made Blotting’, which soon became known as ‘Ford’s Blotting’ following a change of ownership. Blotting paper came to be associated with a range of accessories including the rocker blotter. These blotters were made of materials including wood and metal and typically consisted of three separable parts: a handle; a flat, rectangular part; and a piece with a curved underside. The paper was placed against the curved edge, pressed between the curved and flat elements, and secured in place by the handle when it was screwed through the parts below. This particular blotter was acquired with an old piece of blotting paper secured into position. Rocker blotters were decorated in a range of ways, including using Mauchline Ware techniques. Mauchline Ware Mauchline Ware has also been referred to by names including ‘Scottish white wood production’ and ‘Scottish fancy goods’. Its three most characteristic features are the wood used, the finishes applied and the final varnishing process. Almost all Mauchline Ware is made from plane, also known as sycamore. Features of this wood that make it suitable for decorative goods include lack of knots, close texture and resistance to warping. The six most common finishes of Mauchline Ware have been described by David Trachtenberg and Thomas Keith (Mauchline Ware: A Collector's Guide) as Transfer, Tartan, Fern, Photographic, Black Lacquer and Victorian Illustration. Numerous coats of durable copal varnish (tree resin) provide protection and maintain the pale colour of the plane on pieces where the wood is not fully covered by a decorative finish. Mauchline Ware was widely produced in Mauchline but also Ayrshire, Scotland more broadly by the mid-1840s. At the start of the century the county had been a major producer of snuff boxes made from plane and hand-decorated with paint or pen and ink. It is thought that the wood was usually sourced locally. As snuff (powdered tobacco) went out of fashion in the 1820s, and as the demand for souvenirs rose with the expansion of the railways, the industry needed to evolve. Many companies started to produce a range of small goods in a variety of finishes, the dominant one being Transfer, which was suitable for souvenirs because it could easily depict places. Scottish manufacturers are thought to have purchased engraved plates depicting a range of places and to have exported widely to the areas depicted on their products. The Transfer technique was an attempt to replicate the labour-intensive process of hand-drawing pen and ink pictures, known as ‘washes’. At the start of the Transfer process the item was coated in two or three layers of shellac (insect resin dissolved in alcohol). A print of an engraving was made on a special kind of paper which was varnished and placed on the object ink side down and left to dry for a couple of hours. The print was wetted and the paper, durable but fine enough to be sponged away, was rubbed off. Finally, up to twelve coats of durable copal varnish were applied, a process that could take up to twelve weeks. It is not known precisely when and where the Transfer method was first used. Earlier in the nineteenth century Johann Georg Hiltl and his son Anton Hiltl were using this method in modern day Germany, then Bavaria (see V&A W.9:1 to 2-1965). But certainly it was widely used in Ayrshire from the mid-1840s, where it was likely introduced by the Smiths of Mauchline. This family business was established in 1810. Initially the company specialised in a few areas including snuff boxes, but it soon expanded its offering and methods and came to dominate the Mauchline Ware market, which reached its zenith between 1860 and 1900. Mauchline Ware continued to be made until the 1930s. A fire at the Smiths’ last factory in 1933 effectively ended production and the factory closed in 1939. This last factory was in Mauchline, but the Smiths also operated in Birmingham, England, apparently from around the late 1820s until 1904. Similar goods are known to have been made in Germany when this style had its heyday. Such pieces were often marked ‘Made in Germany’ from the late 1880s in line with the Merchandise Marks Act 1887. This blotter (CIRC.406-1975) The Smiths may have produced this blotter. The name of the manufacturer does not appear to be given on the item itself, but companies rarely applied their names to Mauchline Ware, except for their own promotional pieces. Relatedly, Mauchline Ware was often used for advertising as well as souvenirs, particularly by cotton thread companies. It is thought that such goods were often giveaways, gifts to loyal or prospective customers. This blotter in the V&A collection advertises A. & J. Main & Co. Ltd, ironmongers established in the later 1860s in Glasgow, Scotland. The blotter appears to have been made between around 1906 to 1914. It cannot have been produced at a much earlier date because it was during or around 1906 that A. & J. Main acquired Arrol Bridge & Roof Co.’s Germiston Works in Glasgow, which is referenced on the blotter. The blotter is not likely to have been made during World War I (1914 to 1918) and the style of the lettering, particularly that used for the company name, suggests an earlier date. 1919 to 1922 can also be ruled out as the company went by Armstrongs and Main during this period. Further, Mauchline Ware ceased to be produced in the 1930s and A. & J. Main closed down in 1968. The structures depicted were selected to advertise A. & J. Main’s ironwork business. Some of the scenes may be generic designs like most of the illustrations in A. & J. Main catalogues. Such designs might already have been held by the company that produced the blotter. It is more likely that A. & J. Main commissioned them. The Smiths are known to have made items to order. At least one of the vignettes, the bridge on the proper right of the blotter, depicted a real structure: Connel Ferry Bridge, constructed in 1903 as a railway bridge crossing Loch Etive in Scotland (the bridge is now used as a road and called Connel Bridge). Although A. & J. Main were not responsible for the construction of this bridge, by the time the company commissioned this blotter they had taken over Arrol Bridge & Roof Co. who had recently built Connel Ferry Bridge. It was common for advertising Mauchline Ware to depict places with which companies were associated, as demonstrated by a needlecase in the V&A collection that features Ballochmyle Creamery in Mauchline where ‘Seafoam’ (said to be the first margarine made using vegetable, rather than animal, fats) was made from the late nineteenth century (CIRC.425&A-1975). As indicated by products including this needlecase, Mauchline Ware almost always states the name of the place depicted below the image, but such information is not provided on this blotter. The places referenced on the object indicate A. & J. Main’s international reach. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | CIRC.406-1975 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 24, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest