Tile

1530-1540 (made)

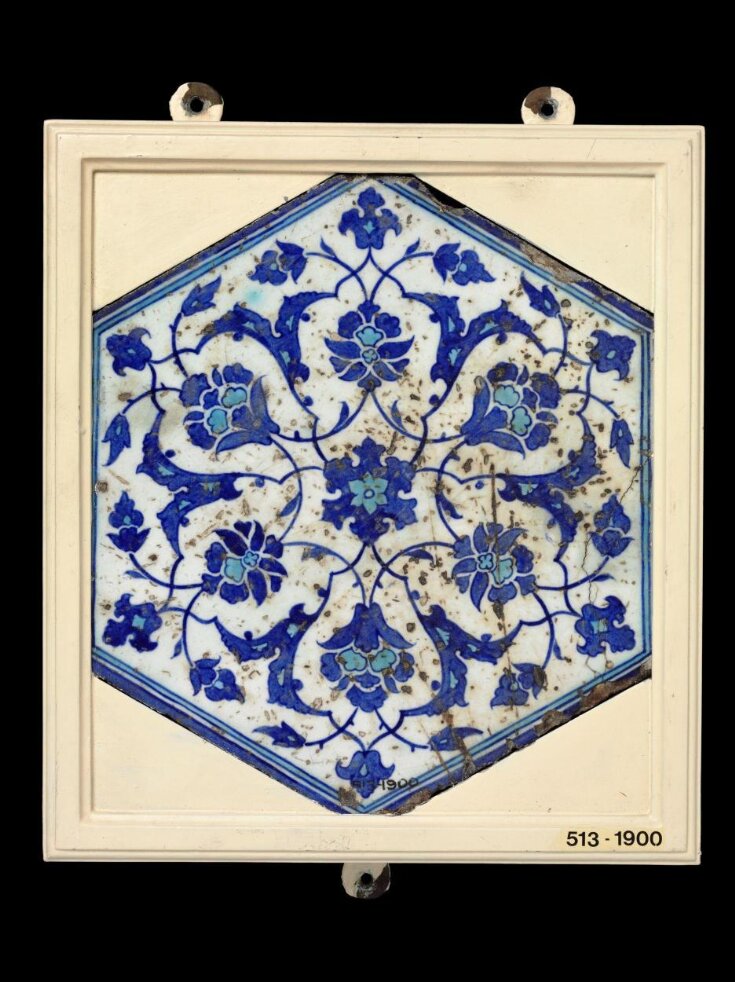

Hexagonal tile of fritware (also called stone paste), painted under the glaze in two shades of blue on a white ground. The sixfold pattern is a combination of hatâyî and rûmî scrollwork, which are given equal visual weight. The pattern is self-contained, being set within a narrow border in three colours. In the hatâyî scrollwork, six composite, stencil-like blossoms of two alternating types are linked by curving stems. The stems continue beyond the blossoms and end in pairs of motifs – small leaves are associated with one type of blossom, and flower buds with the other. The hatâyî pattern is therefore open-ended, whereas the rûmî pattern is closed, forming six compartments that enclose the six hatâyî blossoms. The cusped stems of the rûmî pattern, emerging from a central rosette, bear stylized leaf forms (split palmettes), with further stems emerging from their two tips. Pairs of these outer stems are joined, completing the compartments and supporting small palmettes of two alternating types that fill the corners of the tile.

Object details

| Object type | |

| Brief description | Tile, fritware body, painted under the glaze in two shades of blue, Turkey (Iznik), 1530s; from the Çinili Hamam (Tiled Bath-house) in the Zeyrek district of Istanbul. |

| Physical description | Hexagonal tile of fritware (also called stone paste), painted under the glaze in two shades of blue on a white ground. The sixfold pattern is a combination of hatâyî and rûmî scrollwork, which are given equal visual weight. The pattern is self-contained, being set within a narrow border in three colours. In the hatâyî scrollwork, six composite, stencil-like blossoms of two alternating types are linked by curving stems. The stems continue beyond the blossoms and end in pairs of motifs – small leaves are associated with one type of blossom, and flower buds with the other. The hatâyî pattern is therefore open-ended, whereas the rûmî pattern is closed, forming six compartments that enclose the six hatâyî blossoms. The cusped stems of the rûmî pattern, emerging from a central rosette, bear stylized leaf forms (split palmettes), with further stems emerging from their two tips. Pairs of these outer stems are joined, completing the compartments and supporting small palmettes of two alternating types that fill the corners of the tile. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | This tile once decorated a bathhouse in the Zeyrek district of Istanbul. The bath was designed by the famous court architect, Sinan (d. 1588), and the tiles that decorate the building relate to those made for the imperial palace in the same period. So extensive was the use of tiling on its walls that the building came to be known as the Çinili Hamam, the Tiled Bathhouse. Patronage. Since it opened, probably in the 1530s, the bathhouse has been associated with Barbaros Hayreddin Paşa, called Barbarossa in Western sources, who is famous as the Ottoman empire’s greatest naval commander. The admiral, whose original given name was Hıdır, was born on the island of Lesbos about 1478. He began his naval career as a privateer, and in the 1510s he assisted his elder brother Oruç in establishing a “sultanate” with ever-changing borders in what is now Algeria and Tunisia. There they confronted the Spanish, whom Oruç was killed fighting in 1518. Barbarossa succeeded him, ruling under Ottoman suzerainty. In 1534 he swapped his province for command of the Ottoman navy with the title of “captain of the sea” (<i>kapudan-ı deryâ</i>). He held this post until his death in 1546, carrying out a series of successful campaigns against the Spanish and their allies, often in co-operation with the French. After his arrival in Istanbul in 1534, Barbarossa began to erect religious foundations in the city, of which only his tomb in the Beşiktaş district survives. The admiral acquired the bathhouse in the Zeyrek district so that the profits could support these foundations. Dispersal. The bathhouse underwent various vicissitudes over its history, including several major fires that destroyed the surrounding district and damaged the building. By the later 19th century, the remaining tilework was in poor condition, and most of the tiles were removed and sold to a dealer called Ludovic Lupti, probably in 1874. Lupti marketed them in Paris. From the 1890s to the 1950s, many examples were acquired by the V&A. At the time the Museum was unaware of their origin or even of the fact that they all came from one building. Excavation and conservation work on the bathhouse in 2010-22 established the connection beyond doubt. This tile was purchased from the executor of the British collector W.J. Myers. Myers had had a cordial relationship with the V&A, and in his will, he stipulated that his collections of glass and tiles be offered to the museum for £3000 and £1000 respectively. Myers died in October 1899, and on 3 January 1900, his executor wrote to the Museum making the offer he had stipulated. A valuation process then followed, and on 24 January Frederick Ducane Godman and George Salting, as advisers to the museum, signed a letter to the Director firmly recommending purchase. The objects were then delivered to the V&A, where they were divided in three parts. Two parts, listed in separate inventories dated 23 May 1900, were sent to the South Kensington Museum’s sister institutions in Edinburgh and Dublin. The third and largest part remained at the Museum. Invoices for the glass and tiles were paid on 5 June 1900, at £2253.15s.0d for the glass and £829.15s.0d for the tiles. The two tiles accessioned as 508 and 513-1900 are now identified as coming from the Çinili Hamam in the Zeyrek district of Istanbul. |

| Associated objects |

|

| Bibliographic reference | Aslı Özbay and Aykut Şengözer (editors), Barbarossa's Çinili Hamam: A Masterpiece by Sinan, Istanbul, 2023. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 513-1900 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 24, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest