Mosaic Portrait

1828 (dated)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The term ‘micromosaic’ describes mosaics made of the smallest glass pieces (known as tesserae). Some contain more than 5,000 pieces per square inch. Roman mosaicists developed this technique in the 18th century. Increasing the range of colours available in opaque glass was as important as improving setting methods and surface finish. The goal was to create portable miniature mosaics of hitherto unknown virtuosity that looked as if they were painted. They becane a popular high-end Roman souvenir in the 19th century.

Cavaliere Michelangelo Barberi (1787-1867) trained as a painter and mosaicist and excelled in this technique by bringing together innovative, distinct designs, the best materials and extraordinary craftsmanship. Barberi, a philosopher as much as a maker, postulated in an album of his works published in 1856 that technical perfection was not an aim in itself, but rather a ‘service to Rome’ and Italy.

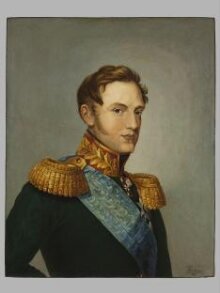

This mosaic portrait, dated 1828, is a tour de force of mosaic-making, based upon a series of portraits by British artist George Dawe. It was created by Barberi as a means to showcase his ability to rival painted portraits in the 'more durable' mosaic technique. Using only the smallest glass pieces, each carefully heated and shaped and added very much in the same way in which a painter would use a brushstroke. Therefore micromosaics may take many years to complete as this piece exemplifies: the young Barberi probably began this extraordinary portrait before Tsar Nicholas I (1796–55) succeeded to the throne in 1825, while the date 1838 implies that it was only finished three year's into the new Tsar's reign.

Imperial commissions followed over the following years, even though this particular work remained in the artist's possession: Barberi showed this early work at the Paris Exhibition of 1855 as part of a larger collection of mosaics before giving the whole group to the London Museum of Practical Geology.

Cavaliere Michelangelo Barberi (1787-1867) trained as a painter and mosaicist and excelled in this technique by bringing together innovative, distinct designs, the best materials and extraordinary craftsmanship. Barberi, a philosopher as much as a maker, postulated in an album of his works published in 1856 that technical perfection was not an aim in itself, but rather a ‘service to Rome’ and Italy.

This mosaic portrait, dated 1828, is a tour de force of mosaic-making, based upon a series of portraits by British artist George Dawe. It was created by Barberi as a means to showcase his ability to rival painted portraits in the 'more durable' mosaic technique. Using only the smallest glass pieces, each carefully heated and shaped and added very much in the same way in which a painter would use a brushstroke. Therefore micromosaics may take many years to complete as this piece exemplifies: the young Barberi probably began this extraordinary portrait before Tsar Nicholas I (1796–55) succeeded to the throne in 1825, while the date 1838 implies that it was only finished three year's into the new Tsar's reign.

Imperial commissions followed over the following years, even though this particular work remained in the artist's possession: Barberi showed this early work at the Paris Exhibition of 1855 as part of a larger collection of mosaics before giving the whole group to the London Museum of Practical Geology.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Mosaic |

| Brief description | Micromosaic portrait of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, Michelangelo Barberi, Rome, dated 1828 |

| Physical description | Micromosoaic portait of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, after the painting by George Dawe; Nicholas depicted as Grand Duke, bust portrait to right, in military uniform ; the polished mosaic set using the 'smalti filati' technique, set in iron tray, probably on a marble base |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Signed and dated by Michelangelo Barberi, lower right |

| Object history | Given by the artist. Transferred to the V&A from the Museum of Practical Geology, Jermyn Street, London The mosaic was part of an entire collection of mosaics and related materials given by Michelangelo Barberi to the Museum of Practical Geology. When the museum was closed in 1901, this group was distributed between the V&A and Natural History Museum. |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | The term ‘micromosaic’ describes mosaics made of the smallest glass pieces (known as tesserae). Some contain more than 5,000 pieces per square inch. Roman mosaicists developed this technique in the 18th century. Increasing the range of colours available in opaque glass was as important as improving setting methods and surface finish. The goal was to create portable miniature mosaics of hitherto unknown virtuosity that looked as if they were painted. They becane a popular high-end Roman souvenir in the 19th century. Cavaliere Michelangelo Barberi (1787-1867) trained as a painter and mosaicist and excelled in this technique by bringing together innovative, distinct designs, the best materials and extraordinary craftsmanship. Barberi, a philosopher as much as a maker, postulated in an album of his works published in 1856 that technical perfection was not an aim in itself, but rather a ‘service to Rome’ and Italy. This mosaic portrait, dated 1828, is a tour de force of mosaic-making, based upon a series of portraits by British artist George Dawe. It was created by Barberi as a means to showcase his ability to rival painted portraits in the 'more durable' mosaic technique. Using only the smallest glass pieces, each carefully heated and shaped and added very much in the same way in which a painter would use a brushstroke. Therefore micromosaics may take many years to complete as this piece exemplifies: the young Barberi probably began this extraordinary portrait before Tsar Nicholas I (1796–55) succeeded to the throne in 1825, while the date 1838 implies that it was only finished three year's into the new Tsar's reign. Imperial commissions followed over the following years, even though this particular work remained in the artist's possession: Barberi showed this early work at the Paris Exhibition of 1855 as part of a larger collection of mosaics before giving the whole group to the London Museum of Practical Geology. |

| Bibliographic reference | List of Works of Art acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum during the Year 1901. Jermyn Street Collection. Part III London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office. Wyman and Sons. 1904. pp.148 |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 4633-1901 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | May 27, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest