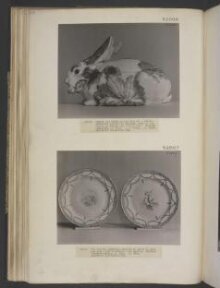

Tureen and Cover

ca. 1755 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

In March 1755 the major London auctioneer Mr Ford held a fifteen day sale of ‘the last Year’s large and valuable Production of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory’, the success of which perhaps led to another sale, again lasting fifteen days, the following year. Chelsea was in many respects the pre-eminent early English porcelain factory, and the years in which these sales took place – the only ones from this decade for which the catalogues survive – was one of its finest periods. The factory’s earliest datable productions were the small ‘goat-and-bee’ jugs, some of which are dated 1745. But during the early 1750s it gained increasing mastery of firing its glassy, soft-paste porcelain body, and by the middle of the decade, when Mr Ford’s sales took place, it was able to successfully fire large pieces. The most notable of these are the striking and ambitious tureens naturalistically modelled and enamelled as birds and animals – many of them life-size, like this rabbit – that were such a marked feature of these two sales. It is clear that today’s high estimation of these productions was shared by Mr Ford’s cataloguer, who drew attention to the finest lots with beguiling descriptions embellished with italics, and, in the case of exceptional pieces, with capitals also: he described this model, eight examples of which were included in the sales, as ‘A beautiful TUREEN in the form of a RABBIT as large as life, and a fine dish to ditto’, and with similar variations.

Other tureens of this type made around 1755-56, and bearing the factory mark of a red anchor, were modelled as artichokes, asparagus, cauliflowers, melons, plaice, carp, eels, ducks, pigeons, partridges, chickens, boar’s heads, and even swans; and while it is clear that their inspiration came from Meissen, Chelsea took to the idea with greater enthusiasm than the Saxon factory ever had. Evidence for this derivation lies in a remarkable sequence of letters dated 1751 from Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, the British Envoy to the Saxon court of Augustus III at Dresden. In these Sir Charles states that he had received a request for examples of Meissen porcelain (which could not then be legally imported into Britain for commercial sale) ‘to furnish the Undertakers’ of the Chelsea works ‘with good designs’. He replied that it ‘would be better & Cheaper for the Manufacturers … to take away any of my China … [in London] and to copy what they like.’ That they did so is confirmed by several Chelsea dessert table figures closely based on Meissen porcelain owned by Sir Charles. Three lists of the components of Meissen dessert service intended for Hanbury Williams also survive, and among the pieces itemized are ‘12 Compotiers [dessert tureens] in form of an artichoke’ and a further twelve dessert tureens shaped as ‘Sun Flowers with handles’ with matching dishes, the latter of which were certainly copied at Chelsea. It is highly likely therefore that Hanbury Williams’s loans prompted Chelsea’s creation of such naturalistic vegetable and zoomorphic serving vessels as this rabbit tureen. The fashion soon spread to other English porcelain factories in the 1750s, notably Bow, Worcester and Longton Hall, and it resurfaced in Wedgwood’s pineapple and cauliflower tea-wares of the following decade. On the continent it enjoyed a long life, making an early appearance at the Strasbourg and Sceaux tin-glazed pottery factories and lasting well into the nineteenth century in earthenware production.

It is far from clear how this rabbit tureen would have been used. Trompe l’oeil table decoration and naturalistic serving vessels had been a feature of grand dining since at least the Renaissance. During the eighteenth century such decoration was particularly associated with the dessert course, though it appears also on silver soup tureens and other vessels used for savoury foods. We know from Mr Ford’s sale catalogues, and from a letter from Benjamin Franklin to his wife, that some of Chelsea’s smaller tureens shaped as vegetables were intended for stewed fruit or creams served during the dessert, and the same is true of a much smaller version of this rabbit. The exterior form of Chelsea’s naturalistic pieces cannot therefore be taken as indicating the general nature their contents, and indeed any contrast between their zoomorphic shape and what they contained must have been deliberate and intended to delight and surprise. Some of the larger animal tureens, like this rabbit, do appear to have been made for serving savoury foods. Certainly, they are simply called ‘tureens’ in the catalogues and not identified as ‘for the desart.’ In the case of the boar’s head tureen, the sword and other hunting accoutrements adorning its under-dish strongly suggest that it was intended for boar, or at least game. However, as all the large zoomorphic pieces lack internal liners and have irregularly shaped flat-bottomed interiors, they can never have been practical vessels for serving soups, ragouts and olios, the normal contents of large tureens used during the savoury courses. Perhaps this impracticality contributed to the short life of trompe l’oeil forms at Chelsea. All were originally equipped with under-dishes, often decorated with ‘proper ornaments’, but being large and flat these were easily broken and very few survive.

Other tureens of this type made around 1755-56, and bearing the factory mark of a red anchor, were modelled as artichokes, asparagus, cauliflowers, melons, plaice, carp, eels, ducks, pigeons, partridges, chickens, boar’s heads, and even swans; and while it is clear that their inspiration came from Meissen, Chelsea took to the idea with greater enthusiasm than the Saxon factory ever had. Evidence for this derivation lies in a remarkable sequence of letters dated 1751 from Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, the British Envoy to the Saxon court of Augustus III at Dresden. In these Sir Charles states that he had received a request for examples of Meissen porcelain (which could not then be legally imported into Britain for commercial sale) ‘to furnish the Undertakers’ of the Chelsea works ‘with good designs’. He replied that it ‘would be better & Cheaper for the Manufacturers … to take away any of my China … [in London] and to copy what they like.’ That they did so is confirmed by several Chelsea dessert table figures closely based on Meissen porcelain owned by Sir Charles. Three lists of the components of Meissen dessert service intended for Hanbury Williams also survive, and among the pieces itemized are ‘12 Compotiers [dessert tureens] in form of an artichoke’ and a further twelve dessert tureens shaped as ‘Sun Flowers with handles’ with matching dishes, the latter of which were certainly copied at Chelsea. It is highly likely therefore that Hanbury Williams’s loans prompted Chelsea’s creation of such naturalistic vegetable and zoomorphic serving vessels as this rabbit tureen. The fashion soon spread to other English porcelain factories in the 1750s, notably Bow, Worcester and Longton Hall, and it resurfaced in Wedgwood’s pineapple and cauliflower tea-wares of the following decade. On the continent it enjoyed a long life, making an early appearance at the Strasbourg and Sceaux tin-glazed pottery factories and lasting well into the nineteenth century in earthenware production.

It is far from clear how this rabbit tureen would have been used. Trompe l’oeil table decoration and naturalistic serving vessels had been a feature of grand dining since at least the Renaissance. During the eighteenth century such decoration was particularly associated with the dessert course, though it appears also on silver soup tureens and other vessels used for savoury foods. We know from Mr Ford’s sale catalogues, and from a letter from Benjamin Franklin to his wife, that some of Chelsea’s smaller tureens shaped as vegetables were intended for stewed fruit or creams served during the dessert, and the same is true of a much smaller version of this rabbit. The exterior form of Chelsea’s naturalistic pieces cannot therefore be taken as indicating the general nature their contents, and indeed any contrast between their zoomorphic shape and what they contained must have been deliberate and intended to delight and surprise. Some of the larger animal tureens, like this rabbit, do appear to have been made for serving savoury foods. Certainly, they are simply called ‘tureens’ in the catalogues and not identified as ‘for the desart.’ In the case of the boar’s head tureen, the sword and other hunting accoutrements adorning its under-dish strongly suggest that it was intended for boar, or at least game. However, as all the large zoomorphic pieces lack internal liners and have irregularly shaped flat-bottomed interiors, they can never have been practical vessels for serving soups, ragouts and olios, the normal contents of large tureens used during the savoury courses. Perhaps this impracticality contributed to the short life of trompe l’oeil forms at Chelsea. All were originally equipped with under-dishes, often decorated with ‘proper ornaments’, but being large and flat these were easily broken and very few survive.

Delve deeper

Discover more about this object

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Soft-paste porcelain painted with enamels |

| Brief description | Tureen and cover of soft-paste porcelain painted with enamels, in the form of a rabbit, made by Chelsea Porcelain factory, Chelsea, ca. 1755. |

| Physical description | Tureen and cover of soft-paste porcelain painted with enamels, in the form of a rabbit. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Credit line | Given by Lady Charlotte Schreiber |

| Object history | Purchased by Lady Charlotte Schreiber from Van Minden, Rotterdam, for £4 in May 1876. Lady Charlotte once enthusiastically remarked that “searching out old china was pure pleasure.” |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | In March 1755 the major London auctioneer Mr Ford held a fifteen day sale of ‘the last Year’s large and valuable Production of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory’, the success of which perhaps led to another sale, again lasting fifteen days, the following year. Chelsea was in many respects the pre-eminent early English porcelain factory, and the years in which these sales took place – the only ones from this decade for which the catalogues survive – was one of its finest periods. The factory’s earliest datable productions were the small ‘goat-and-bee’ jugs, some of which are dated 1745. But during the early 1750s it gained increasing mastery of firing its glassy, soft-paste porcelain body, and by the middle of the decade, when Mr Ford’s sales took place, it was able to successfully fire large pieces. The most notable of these are the striking and ambitious tureens naturalistically modelled and enamelled as birds and animals – many of them life-size, like this rabbit – that were such a marked feature of these two sales. It is clear that today’s high estimation of these productions was shared by Mr Ford’s cataloguer, who drew attention to the finest lots with beguiling descriptions embellished with italics, and, in the case of exceptional pieces, with capitals also: he described this model, eight examples of which were included in the sales, as ‘A beautiful TUREEN in the form of a RABBIT as large as life, and a fine dish to ditto’, and with similar variations. Other tureens of this type made around 1755-56, and bearing the factory mark of a red anchor, were modelled as artichokes, asparagus, cauliflowers, melons, plaice, carp, eels, ducks, pigeons, partridges, chickens, boar’s heads, and even swans; and while it is clear that their inspiration came from Meissen, Chelsea took to the idea with greater enthusiasm than the Saxon factory ever had. Evidence for this derivation lies in a remarkable sequence of letters dated 1751 from Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, the British Envoy to the Saxon court of Augustus III at Dresden. In these Sir Charles states that he had received a request for examples of Meissen porcelain (which could not then be legally imported into Britain for commercial sale) ‘to furnish the Undertakers’ of the Chelsea works ‘with good designs’. He replied that it ‘would be better & Cheaper for the Manufacturers … to take away any of my China … [in London] and to copy what they like.’ That they did so is confirmed by several Chelsea dessert table figures closely based on Meissen porcelain owned by Sir Charles. Three lists of the components of Meissen dessert service intended for Hanbury Williams also survive, and among the pieces itemized are ‘12 Compotiers [dessert tureens] in form of an artichoke’ and a further twelve dessert tureens shaped as ‘Sun Flowers with handles’ with matching dishes, the latter of which were certainly copied at Chelsea. It is highly likely therefore that Hanbury Williams’s loans prompted Chelsea’s creation of such naturalistic vegetable and zoomorphic serving vessels as this rabbit tureen. The fashion soon spread to other English porcelain factories in the 1750s, notably Bow, Worcester and Longton Hall, and it resurfaced in Wedgwood’s pineapple and cauliflower tea-wares of the following decade. On the continent it enjoyed a long life, making an early appearance at the Strasbourg and Sceaux tin-glazed pottery factories and lasting well into the nineteenth century in earthenware production. It is far from clear how this rabbit tureen would have been used. Trompe l’oeil table decoration and naturalistic serving vessels had been a feature of grand dining since at least the Renaissance. During the eighteenth century such decoration was particularly associated with the dessert course, though it appears also on silver soup tureens and other vessels used for savoury foods. We know from Mr Ford’s sale catalogues, and from a letter from Benjamin Franklin to his wife, that some of Chelsea’s smaller tureens shaped as vegetables were intended for stewed fruit or creams served during the dessert, and the same is true of a much smaller version of this rabbit. The exterior form of Chelsea’s naturalistic pieces cannot therefore be taken as indicating the general nature their contents, and indeed any contrast between their zoomorphic shape and what they contained must have been deliberate and intended to delight and surprise. Some of the larger animal tureens, like this rabbit, do appear to have been made for serving savoury foods. Certainly, they are simply called ‘tureens’ in the catalogues and not identified as ‘for the desart.’ In the case of the boar’s head tureen, the sword and other hunting accoutrements adorning its under-dish strongly suggest that it was intended for boar, or at least game. However, as all the large zoomorphic pieces lack internal liners and have irregularly shaped flat-bottomed interiors, they can never have been practical vessels for serving soups, ragouts and olios, the normal contents of large tureens used during the savoury courses. Perhaps this impracticality contributed to the short life of trompe l’oeil forms at Chelsea. All were originally equipped with under-dishes, often decorated with ‘proper ornaments’, but being large and flat these were easily broken and very few survive. |

| Bibliographic reference | Hilary Young, ‘As Big as Life’ , in 30 Objects 30 Insights, Rachel Gotlieb and Karine Tsoumis (eds.), Gardiner Museum, Toronto, 2014, pp. 112-117 |

| Other number | Sch. I 151:1, 2 - Schreiber number |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 414:328/1, 2-1885 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 16, 2008 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest