Teapot

1886 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

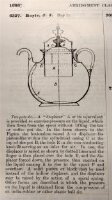

This 'Self-Pouring Teapot' was made in Sheffield in around 1886 by James Dixon and Sons following a patent registered that year by J.J. Royle of Manchester. It is made from Britannia Metal, an inexpensive industrial metal that grew out of factory mechanisation developed in the city. The self-pouring teapot was the precursor to the modern percolator. A cylinder fixed to the underside of the lid enabled the lid to act as a piston. A hole in the wooden finial allowed air in. By lifting the lid and piston and then pressing the lid back down while holding a finger over the hole in the finial, pneumatic pressure inside the teapot forced the tea up and out of the spout. The teapot was invented as a novelty but sold in thousands.

The Self-Pouring Teapot came in Britannia Metal made by James Dixon and Sons of Sheffield, and patterned ceramic, made by Royal Doulton. Britannia Metal is an alloy consisting of between 92 and 97% tin with small amounts of antimony and copper. It could be cast, spun, hammered (raised or sunk), stamped, pierced, and engraved in ways other metals could not. From the 1840s, it was also used as a base for electroplate: an object with the mark EPBM on it denotes Electroplated Britannia Metal.

Britannia Metal's cheapness and ubiquity often leave it overlooked in histories of the metal trades but it was subject to all the same design influences as other metals and put mechanised product-design in more homes than ever before.

The Self-Pouring Teapot came in Britannia Metal made by James Dixon and Sons of Sheffield, and patterned ceramic, made by Royal Doulton. Britannia Metal is an alloy consisting of between 92 and 97% tin with small amounts of antimony and copper. It could be cast, spun, hammered (raised or sunk), stamped, pierced, and engraved in ways other metals could not. From the 1840s, it was also used as a base for electroplate: an object with the mark EPBM on it denotes Electroplated Britannia Metal.

Britannia Metal's cheapness and ubiquity often leave it overlooked in histories of the metal trades but it was subject to all the same design influences as other metals and put mechanised product-design in more homes than ever before.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Britannia Metal |

| Brief description | Self-pouring teapot, Britannia Metal, marked 'ROYLE'S PATENT SELF-POURING No. 6327, 1886' and 'MANUFACTURED BY JAMES DIXON & SONS, SHEFFIELD, FOR J.J. ROYLE, MANCHESTER' and a pattern number 108/2, 1886 |

| Physical description | Self-pouring teapot, Britannia Metal, wide, round, upwards-expanding body with a circular neck with a band of simulated, bright-cut ornament, separate lid with wooden finial, small Britannia Metal handle with spreading fixings, cylindrical spout curving up and over so that it points downward, marked 'ROYLE'S PATENT SELF-POURING No. 6327, 1886' and 'MANUFACTURED BY JAMES DIXON & SONS, SHEFFIELD, FOR J.J. ROYLE, MANCHESTER' and a pattern number 108/2, 1886 |

| Dimensions |

|

| Production type | Mass produced |

| Marks and inscriptions | ROYLE'S PATENT SELF-POURING No. 6327, 1886 / MANUFACTURED BY JAMES DIXON & SONS, SHEFFIELD, FOR J.J. ROYLE, MANCHESTER' / 108/2, 1886 Note Maker's trademark |

| Credit line | From the David Lamb Collection: given in memory of David Lamb by Joan Lamb |

| Object history | This 'Self-Pouring Teapot' was made in Sheffield in around 1886 by James Dixon and Sons following a patent registered that year by J.J. Royle of Manchester. It is made from Britannia Metal, an inexpensive industrial metal that grew out of factory mechanisation developed in the city. These teapots were also made in brightly coloured ceramics by Royal Doulton. John James Royle J.J. Royle's Patent Self-Pouring Teapot is a precursor to the modern percolator. Fixed under its lid is a hollow, cylindrical, tinned copper-alloy piston that can be drawn upwards from the teapot by lifting the lid. The small, wooden finial on the lid has a hole in the middle to allow air inside as the lid is lifted. Covering this hole with your finger and pushing the lid down towards the teapot increases the air pressure inside and forces the tea up and out of the spout. The system is simple and efficient and works extremely well. John James Royle (b. 1850), was an engineer whose foundry at 27 King Street West, Manchester, produced industrial heating equipment and evaporators for commercial use. His desgn for a self-pouring teapot, which he patented on 11 May 1886, was one of a number of novel inventions he produced primarily to draw attention to his firm's products. He also invented a mechanical egg beater, a timed egg boiler and a smokeless fuel stove. According to advertisements by Royle and other companies who sold his teapot, there was an urgent need, during the mid 1880s, for a labour-saving device that, 'does away entirely with the drudgery of lifting the Tea-Pot' (Retailers Paine, Diehl & Co., Philadelphia). 'No more aching arms as the teapot has not to be lifted' / 'Why, in these days of mechanical science, should it be considered necessary to lift a heavy teapot to serve tea?' (John J. Royle, Manchester). An anonymous advertisement sold the teapot as 'a little bit of engineering in the right place. Success is made up of apparent trifles.' Royle's self-pouring teapot, possibly to his surprise given its novelty, became a huge hit, selling tens of thousands in both Britain and the US and is the item for which he is most remembered. Royle's invention was timely and may have been targeted deliberately towards showing at the Royal Jubilee Exhibition in Manchester in 1887. There it caught the attention of the Prince and Princess of Wales. According to the Swansea and Glamorgan Herald on Wednedsay 14 September 1887, "It may be mentioned that the self-pouring teapot has attracted not a little attention in the Royal Jubilee Exhibition at Manchester, even that of Royalty itself. It will be remembered that the exhibition was opened by T.R.H The Prince and Princess of Wales, and in describing the opening of the exhibition the Manchester said, 'It was observed that the attention of the Princess of Wales was attracted to a moving model of Royle's patent self-pouring teapot, an exhibit consisting of a glass case enclosing a lady's (wax) hand in the act of pressing down the lid of the improved teapot to pour out the tea. The Royal party stopped at this exhibit, and had the action explained to them, and upon witnessing that a lady could now really pour out tea without lifting the teapot, her Royal Highness the Princess expressed her delight with it and exclaimed, 'It is charming.' The Heir Apparent had the operation repeated, and was evidently more puzzled than charmed, for in seeing the tea pour itself out of the spout his Royal Highness exclaimed 'That is funny,' an expression doubtless prompted by what appeared to be a violation of a natural law, which as suggested to the inventor the name of this ingenious article. viz., a self-pouring teapot." Royle's advertisement for the exhibition also claimed that the teapot saved about 25% of the tea, 'or in other words, the Tea is so much better brewed. This is explained by the tea being forced through the leaves, and not poured off the top as in the old style. The strongest tea is among the leaves.' Not everyone was convinced. In the 'Western Times' on Monday 03 October 1887, 'Our Ladies' Column by 'Penelope'' complained, 'I was amused to watch the process as illustrated by "Royle's patent," though I do not endorse it, for I think pretty hand and arm are seen to advantage when engaged in pouring out tea, and moreover this teapot does not lend itself to the hygienic and only safe way of preparing tea, by not allowing the water to remain in contact with the leaves more than seven minutes, before pouring it into another hot teapot in case of possible delay.' Another complaint was that the hole in the finial allowed hot steam up as much as it forced air pressure down and it was easy to burn a finger. A Royle's Patent Self-Pouring Teapot was presented to the Italian opera singer, Adelina Patti not long after the Manchester Exhibition. On Wednesday 14 September 1887 the Swansea and Glamorgan Herald reported that it was at the time on show, 'in the window of Mr John Legg, Nelson Street, Swansea,' where 'we venture to think [it] will prove on inspection to be an ingenious novelty to the bulk of the residents of our town.' Then known as Adelina Patti-Nicolini, after her marriage the previous year to the tenor, Ernesto Nicolini, she was awarded a 'selfpouring tea pot together with a sugar basin and cream jug of a pattern which his never before been made, and which the makers guarantee will not be repeated in design in order that the queen of song may celebrate five o'clock tea whenever she pleases with an apparatus not less unique in its way than is the celebrated fan in her possession, bearing numerous royal autographs, and of which we have heard so much of late. The service is 'hand made, and is of nickel heavily plated with silver, this being far more durable than if composed entirely of the argentiferous element. It is shown in a handsome portable case, covered with crimson plush, and bearing on the exterior a silver plate on which in engraved Madame Patti -Nicolini's monogram, the design of the service not permitting any inscription on either of the articles comprising it. The whole is a present to madame from the chief members of her personal suite, and as a trifling acknowledgement of the esteem in which they hold their gifted mistress.' James Dixon and Sons The manufacturer, James Dixon was responsible for building one of Sheffield's great metalworking companies, rivalled only in scale in the city by the silversmiths, Walker and Hall, and the cutlers, Joseph Rodgers and Sons. He started primarily as Britannia Metalsmith but by the 1830s also produced silver, Sheffield plate, nickel silver, brass shot flasks and gunpowder belts. He later incorporated electroplating into the firm's products. Dixon began a partnership with the cutler and Britannia Metal maker, Thomas Smith, in Silver Street in around 1807 but had worked before that for some of the earliest factories to produce Britannia metal including Richard Constantine and Broadhead, Gurney and Sporle. In the early 1820s after Smith's retirement, Dixon moved the factory to Cornish Place, possibly named after the source of the factory's tin. This was right on the west bank of the River Don where there was a plentiful water supply. Dixon brought his sons into partnership with him in the 1820s. When William Frederick became a partner in 1824 the business was styled James Dixon and Son. When his second son, James Willis Dixon, became a partner in 1835 the firm took the name James Dixon and Sons. These partnership dates are useful when trying to attribute dates to the company's products as this part of their history can be tracked through the trademarks they applied to them. Between 1835 and 1836, James Willis Dixon travelled in the US to develop the company's vast export business there. By the 1840s, the firm sent Britannia metal and Sheffield Plate to Baltimore and Philadelphia and dominated the US market. When this trade came under threat during the American Civil War (1861-65), the company shifted its attention to France, Russia, Australia and elsewhere opening a London office in the 1870s to manage international affairs. Despite being at the forefront of industrial innovation in the 1820s, operating one of the first steam-powered rolling mills in Sheffield, Dixons were slow to adopt the new alchemy of electroplating when it was introduced by Elkington and Co. in Birmingham in the early 1840s and initially subcontracted this work to Walker and Coulson. In 1848 they finally applied for a licence to 'meet with spirit the electroplating in Sheffield' and by the Great Exhibition of 1851 they won two prizes for their electroplated Britannia Metal which they were instructed to label clearly 'Britannia metal goods' because they were almost indistinguishable from silver. Their surviving trade catalogues from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries show that their stock-in-trade was tea services, dining services, cutlery, sports trophies, communion services, shooting equipment and drinking paraphernalia. Dixons occasionally employed leading designers, including Christopher Dresser, whose designs they manufactured 1879 and 1882. James Dixon and Sons' Cornish Street works employed around 500 workers by the 1860s, this number eventually growing to around 850 by the time of their centenary celebrations in 1906. The factory was enormous and large parts of it survive close to the Ball Street Bridge. Such was the company's impact on the area that the works gave their name to Cornish Street and Dixon Street close by. After the First World War, when the market for luxury goods declined, the firm was on the decline although still survived until the 1950s as a large-scale cutlery factory. The company was eventually bought out and Cornish Place was closed as a factory in 1992. A decade of sad dereliction was reversed early in the 2000s when the vast factory was converted to apartments and shops. |

| Historical context | Britannia Metal is an alloy consisting of between 92 and 97% tin with small amounts of antimony and copper. It was an inexpensive industrial metal that grew out of factory mechanisation developed in Sheffield in the 1760s. It could be cast, spun, hammered (raised or sunk), stamped, pierced, and engraved in ways other metals could not. It also acted as a 'white metal' base for electroplate from the late 1840s. Britannia Metal is highly instructive about manufacturing practices, factory collaborations and networks, competitive ingenuity, social change and aspiration, and the increase in public-facing product-consumption that is not always present in other materials. BRITANNIA METAL ORIGINS Materially at least, Britannia Metal is most like pewter, a soft tin alloy. Pewtersmithing is an ancient craft in which the vast majority of products were cast in moulds using traditional techniques regulated by one of the historic London guilds, the Worshipful Company of Pewterers. Moulds were expensive and styles persisted longer than in more adaptable materials. Britannia Metal was rarely cast, however, and was not regulated by a guild. Britannia Metal is defined far more by mechanical production developed in the production of Sheffield Plate or fused plate. Sheffield Plate was first developed in the 1740s and is silver-plated copper where a copper ingot is plated with silver first and then rolled into a thin sheet to be worked into household goods. It could not be cast and excessive workmanship would pierce the thin veneer so the Sheffield Platers developed weight-driven and eventually hydraulic die-stamps and fly presses that meant designs could be formed and applied in one go with much more predictable regularity. As an industry, it did not come into its own until mid-century, high-relief Rococo designs give way to Robert Adam-inspired, flatter, plainer, interchangeable classical forms that could be produced in large numbers. Classical designs could be created more easily and less expensively from sheet metal. The introduction of steam power (pioneered by James Watt for Matthew Boulton) and crucible steel (developed commercially by Benjamin Huntsman) equipped factories with more powerful rolling mills, encouraging 'white metal' workers to experiment with tin-alloys that could be rolled into sheets. In 1769 the Sheffield metalworker, James Vickers, began producing Britannia Metal after apparently being tipped off by 'a dying friend'. His first pieces wer emade under contract to Ebenezer Hancock and Richard Jessop. His trademark, 'I.VICKERS', is stamped on items made in his factory between 1769 and 1787, the earliest pieces of Britannia Metal in production. A century later, the novelty of mechanised production had still not passed completely. In the 1886 novel 'Patience Wins' (Blackie & Son Ltd, London, Glasgow and Dublin, 1886) George Manville Fenn describes how the hero comes across a Britannia Metal factory: 'As I looked through into these works, one man was busy with sheets of rolled-out Britannia metal, thrusting them beneath a stamping press, and at every clang with which this came down a piece of metal like a perfectly flat spoon was cut out and fell aside, while at a corresponding press another man was holding a sheet, and as close as possible out of this he was stamping out flat forks, which, like the spoons, were borne to other presses with dies, and as the flat spoon or fork was thrust in it received a tremendous blow, which shaped the bowl and curved the handle, while men at vices and benches finished them off with files. ... in spite of the metal being cold, the heat of the friction, the speed at which it goes, and the ductility of the metal make it behave as if it were so much clay or putty." Britannia metal's light robustness had also come to the attention of Charles Dickens. 'Pleasantry, sir!' exclaimed Pott with a motion of the hand, indicative of a strong desire to hurl the Britannia metal teapot at the head of the visitor. 'Pleasantry, sir! - But - no, I will be calm; I will be calm, Sir;' in proof of his calmness, Mr. Pott flung himself into a chair, and foamed at the mouth. ('The Pickwick Papers', Chapter 18) Britannia Metal was therefore developed in Sheffield, a place with no distinctive pewter history, to harness the new factory machinery developed by the Sheffield Platers and became a national industry until the early decades of the twentieth century. The Britannia Metal makers could reach a much wider market with the same equipment. Britannia Metal was not as valuable as silver, not as convincing as Sheffield Plate, not as historic as pewter and not as robust as nickel silver but, industrially, was easier to produce than all of them. It combined the cheapness and accessibility of pewter with the state-of-the-art mass manufacturing methods of Sheffield Plate. BRITANNIA METAL TRADE Britannia Metal's cheapness and ubiquity have led to its neglect by art historians but it was subject to all the same design influences as other metals and ceramics and put mechanised product-design on more tables than ever before. Britannia Metal was the first metal developed during the industrial revolution to reach a wide cross-section of the population. The democratising elements of Sheffield Plate are too often overstated given the number of items that still included space for family crests. Within a few decades of its invention, Britannia Metal tea and coffee sets served travellers on railways, ships and stagecoaches and in the hotels and inns where they stayed. They smoked tobacco stored in Britannia Metal boxes. Taverns and restaurants served beer in Britannia Metal mugs. Communion services in less wealthy parishes used Britannia Metal cups during religious ceremonies. The prevalence of tea and coffee services as early products of Britannia Metal, always with a sugar bowl, reflects the nation's sweetening tooth. Britannia Metal sugar bowls and tobacco boxes, cheaply produced in large numbers for an expanding market, also reflect the increasing demand for - and availability of - the products of empire, the growing consumption of both being primary drivers of the transatlantic slave trade. Britannia Metal production helped put sugar bowls and tobacco boxes on more tables than ever. The Britannia Metal trade was not regulated in the same way as silver or pewter which were both controlled by guilds that kept a close eye on the quality of alloys and production. It came to occupy a grey area with much more freedom. Single workshops might use a variety of alloys for the different parts of objects they suited best. When Elkington of Birmingham developed their patents for electroplating and electrogilding from the 1840s, Britannia Metal became a substrate along with nickel silver for electroplate. This technological advance was significant enough for James Dixon & Sons of Sheffield to show an electroplated Britannia Metal coffee pot at the Great Exhibition of 1851, an example of which is in the V&A's collection (M.23-1999). It was the growing ubiquity of materials like Britannia Metal that extended the reach of commercial product-design, a development that by the 1840s encouraged the early art educators of the Department of Science and Art, who later oversaw the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) to take popular design seriously. Early Britannia Metal is a little-heralded but profoundly democratizing force in the history of product design. It was not to everyone's taste however. Britannia metal was not as durable as other white metals such as German or nickel silver. 'A teapot ... costing seven or eight shillings, will probably not last twelve months, while a teapot of German silver, costing about three pounds, will last fifty years,' claimed the publication 'Cookery and Domestic Economy for Young Housewives' in 1845. TRADEMARKS AND ADVERTISING Britannia Metal makers were great markers of their products. Their marks were not a legally controlled guarantee of quality but an opportunity to advertise using and expanding on established conventions around assumptions of quality. The tradition of using marks and advertising on the bases of their products owes more to pewter history than to the Sheffield Platers who rarely marked their products and were only obliged to for a brief period in the 1770s and 80s. The 'maker's mark' on a piece of Britannia Metal recalls the pewterer's 'touch mark', their legally enforceable guarantee that they would produce high quality metal with no lead it. The Britannia Metal maker's mark was a personal mark of quality rather than a legal guarantee. The habit many Britannia Metal workers had of changing their maker's mark every 15 or 20 years enables Britannia Metal products to be dated within accurate and narrow margins. Like the pewterers, Britannia Metal makers also stamped on advertising slogans championing the quality of their products. Throughout the nineteenth century this advertising became more expansive. Many of them laud the technological miracle offered by a product. Philip Ashberry and Son's 'PATENT NON-CONDUCTING HANDLE' on teapots of around 1850 offered tea drinkers the promise of a cup of tea without blistered fingers. Broadhead & Atkin sold small, bachelor teapots for one with an 'ANTICALORIC HANDLE', a more obscure but convincingly technical way of making the same promise to its lonesome user. And from 1886, James Dixon & Sons 'J.J. Royle's PATENT SELF-POURING TEAPOT' with its oddly constructed spout that pours the tea when you press the lid, was an ingenious precursor of the modern-day percolator. OLD BRITANNIA METAL As Britannia Metal ages it dulls to a matt grey but when new was a reflective 'white metal'. It was not necessarily a substitute for silver but it catered for the same aesthetic for white metals. Lift the lid or peep under the foot of a dark grey Britannia metal teapot and areas that have been protected from the air or from damp will retain the lustre they had on the day they left the factory. The wear and tear on antique Britannia Metal often reveals a long history of use. As it darkens it also reveals the tell-tale signs of manufacturing practices. Seams are visible on the bodies and spouts of teapots revealing how they were stamped in sections and soldered. Pierced sugar bowls and salts cellars show the use of the Sheffield Platers' fly press. Pear-shaped teapots and coffee pots from the 1840s show the advent of spinning on high-powered lathes as a method of production. These features enable close comparisons between matching models in silver, Sheffield Plate, brass, copper, pewter, Britannia Metal and electroplate. Britannia Metal, therefore, wears its construction processes openly enabling a history of mechanised metal manufacturing to be charted over the 150 years or so that it was in production. THE DAVID LAMB COLLECTION This piece is one of 24 Britannia Metal items (Museum Nos. M.26-49-2023) dating from 1770 to 1890, selected by the V&A in 2023 from the collection of the late David Lamb (1935-2021). They were presented as gift to the museum by Joan Lamb, David's wife. David Lamb was a Senior Lecturer and Reader in Pathology at Edinburgh University and a successful photographer and keen fisherman. He began collecting Britannia Metal in 1978 when he bought a teapot on a whim and began to research it. David was a prominent member of the Pewter Society and the Antique Metalware Society and volunteered and guided at the National Museum of Scotland. Among collectors he campaigned hard to counter a bias against Britannia Metal. David recognised early on that Britannia Metal is not simply a cheap tin-alloy that should be ignored by collectors but a game-changing, complex, democratising and aspirational product that is profoundly expressive of industrial, technological and social change. David was also quick to point out that although Britannia Metal owes much in its material properties to pewter, it was only natural it should develop as an industry in Sheffield, a place with no distinct pewter history, because its production methods owed far more to industrial Sheffield Plate manufacture than to pewtersmithing. David was a committed and insatiable collector who also bought pewter, silver and snuffboxes in a variety of materials. As a collector it was his Britannia Metal collection - which grew to over 600 pieces - that made his name. As just about the only person collecting Britannia Metal, he was in the fortunate position of having little competition from collectors and of knowing far more than the people from whom he was buying. Even today, the pieces David collected are not of high financial value but they are of significant historical, technological and educational value. |

| Summary | This 'Self-Pouring Teapot' was made in Sheffield in around 1886 by James Dixon and Sons following a patent registered that year by J.J. Royle of Manchester. It is made from Britannia Metal, an inexpensive industrial metal that grew out of factory mechanisation developed in the city. The self-pouring teapot was the precursor to the modern percolator. A cylinder fixed to the underside of the lid enabled the lid to act as a piston. A hole in the wooden finial allowed air in. By lifting the lid and piston and then pressing the lid back down while holding a finger over the hole in the finial, pneumatic pressure inside the teapot forced the tea up and out of the spout. The teapot was invented as a novelty but sold in thousands. The Self-Pouring Teapot came in Britannia Metal made by James Dixon and Sons of Sheffield, and patterned ceramic, made by Royal Doulton. Britannia Metal is an alloy consisting of between 92 and 97% tin with small amounts of antimony and copper. It could be cast, spun, hammered (raised or sunk), stamped, pierced, and engraved in ways other metals could not. From the 1840s, it was also used as a base for electroplate: an object with the mark EPBM on it denotes Electroplated Britannia Metal. Britannia Metal's cheapness and ubiquity often leave it overlooked in histories of the metal trades but it was subject to all the same design influences as other metals and put mechanised product-design in more homes than ever before. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.48-2023 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 27, 2023 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest