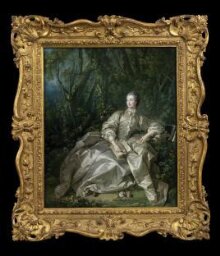

Portrait of Madame de Pompadour

Oil Painting

1758 (painted)

1758 (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

François Boucher (1703-1770) was born in Paris and probably received his first artistic training from his father who was a painter before attending the Académie de France in Rome. He may also have travelled to Naples, Venice and Bologna. Around 1731 Boucher returned to Paris where he rapidly gained the royal favour and interest from the private collectors. He was a very prolific artist and produced a wide range of artworks from pastoral paintings, porcelain and tapestry designs as well as stage designs influencing deeply the new Rococo movement.

This painting is a fine example of the dominant Rococo style in 18th-century France. It depicts the Marquise de Pompadour who became in 1745 the favourite mistress of King Louis XV. She is portrayed in a garden or edges of woods wearing a sumptuous white silk dress which blends in with the ochre green of the vegetation around. This picture is characterised by the combination of a subtle artificiality and sufficient naturalism, which is a typical feature of the Rococo aesthetic. This painting is a good example of how Boucher was probably made to celebrate and consolidate the Marquise’s new status as well as exalting her renowned beauty.

This painting is a fine example of the dominant Rococo style in 18th-century France. It depicts the Marquise de Pompadour who became in 1745 the favourite mistress of King Louis XV. She is portrayed in a garden or edges of woods wearing a sumptuous white silk dress which blends in with the ochre green of the vegetation around. This picture is characterised by the combination of a subtle artificiality and sufficient naturalism, which is a typical feature of the Rococo aesthetic. This painting is a good example of how Boucher was probably made to celebrate and consolidate the Marquise’s new status as well as exalting her renowned beauty.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Portrait of Madame de Pompadour (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Oil on canvas |

| Brief description | Oil on canvas, Portrait of Madame de Pompadour, François Boucher, 1758. |

| Physical description | The Marquise of Pompadour portrayed full-length in a garden. She wears a sumptuous silk dress and holds a book while facing left. All around the picture is filled with vegetation, wild roses and bird. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Styles | |

| Marks and inscriptions | 'f. Boucher 1758' Note Signed and dated by the artist on a stone, lower right |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Bequeathed by John Jones |

| Object history | Bequeathed by John Jones, 1882 Ref : Parkinson, Ronald, Catalogue of British Oil Paintings 1820-1860. Victoria & Albert Museum, HMSO, London, 1990. p.xix-xx John Jones (1800-1882) was first in business as a tailor and army clothier in London 1825, and opened a branch in Dublin 1840. Often visited Ireland, travelled to Europe and particularly France. He retired in 1850, but retained an interest in his firm. Lived quietly at 95 Piccadilly from 1865 to his death in January 1882. After the Marquess of Hertford and his son Sir Richard Wallace, Jones was the principal collector in Britain of French 18th century fine and decorative arts. Jones bequeathed an important collection of French 18th century furniture and porcelain to the V&A, and among the British watercolours and oil paintings he bequeathed to the V&A are subjects which reflect his interest in France. See also South Kensington Museum Art Handbooks. The Jones Collection. With Portrait and Woodcuts. Published for the Committee of Council on Education by Chapman and Hall, Limited, 11, Henrietta Street. 1884. Chapter I. Mr. John Jones. pp.1-7. Chapter II. No.95, Piccadilly. pp.8-44. This gives a room-by-room guide to the contents of John Jones' house at No.95, Piccadilly. Chapter VI. ..... Pictures,... and other things, p.138, "The pictures which are included in the Jones bequest are, with scarcely a single exception, valuable and good; and many of them excellent works of the artists. Mr. Jones was well pleased if he could collect enough pictures to ornament the walls of his rooms, and which would do no discredit to the extraordinary furniture and other things with which his house was filled." Historical significance: This painting is a fine example of the Rococo style Boucher contributed to develop in 18th-century France. Among numerous commissions, Boucher also worked for the Marquise de Pompadour who became, between 1747 and her death in 1764, his most enthusiastic admirer and patron. Among the best known pastoral and the few religious scenes the Marquise commissioned from Boucher, there are also a number of portraits of herself. The present painting portrays the Marquise de Pompadour in a garden that looks like the edges of a wood, a typical feature of artificially recreated nature favoured by the Rococo. She wears a sumptuous silk dress in yellowish white which blends with the scenery depicted in harmonious shades of ochre green. This aesthetic dominated by subdued colours is characteristic of Boucher's art which recreated the genre of the pastoral, fostering an imagery of shepherds and shepherdesses as sentimental lovers that was taken up in every medium, from porcelain to toile de Jouy. He transferred this pastoral atmosphere to other subject matters such as court portraits. The wild roses and the little birds enhance the idyllic atmosphere of the picture while the books allude to the Marquise's reputation as a patroness of the arts. Another portrait of the Marquise in a garden is dated 1759, a year after the V&A version (Wallace collection, London -P418) whereas two earlier portraits depict the Marquise in an interior: one dated 1756 is in the Alte Pinacothek, Munich (Inv.-Nr. HUW 18) and the other is in the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh (NG 429). In these two interior scenes, the Marquise is pictured is the exact same position whilst holding an open book but the palette Boucher employed appears there much more brilliant with saturated colours, another aspect of Boucher's art who oscillates between pastel-like scenes and more vivid although utterly harmonious colour scheme. H. Wine (2002) had suggested that this more chastered representation of the Pompadour displaying an immaculate white dress, was in part a response to unsympathetic criticism that greeted the Munich portrait at the 1757 Salon. In 1758, Boucher painted another portrait of the Marquise which looks quite different in the format and much more intimate. It depicts the Marquise at her toilet (Fogg Art Museum, Harvard, Cambridge) in the middle of a beautifying ritual and oscillates between a courtly and politic interpretation (consolidating her position as a favourite) and a purely private image painted for her brother, the marquis de Marigny. Anyhow Boucher paid here another tribute to her beauty. However Boucher was not the only artist to have portrayed the Marquise but others such as François-Hubert Drouais (1727-1775) portrayed the Marquise in the early 1760s (see The National Gallery, London; Stewart Museum, Montreal, Musée Condé, Chantilly). This approach, characterised by a wealth of picturesque details, dominated French painting until the emergence of Neo-classicism, when criticism was heaped on Boucher and his followers. |

| Historical context | In his encyclopaedic work, Historia Naturalis, the ancient Roman author Pliny the Elder described the origins of painting in the outlining of a man's projected shadow in profile. In the ancient period, profile portraits were found primarily in imperial coins. With the rediscovery and the increasing interest in the Antique during the early Renaissance, artists and craftsmen looked back to this ancient tradition and created medals with profile portraits on the obverse and personal devise on the reverse in order to commemorate and celebrate the sitter. Over time these profile portraits were also depicted on panels and canvas, and progressively evolved towards three-quarter and eventually frontal portraits. These portraits differ in many ways from the notion of portraiture commonly held today as they especially aimed to represent an idealised image of the sitter and reflect therefore a different conception of identity. The sitter's likeness was more or less recognisable but his particular status and familiar role were represented in his garments and attributes referring to his character. The 16th century especially developed the ideal of metaphorical and visual attributes through the elaboration of highly complex portrait paintings in many formats including at the end of the century full-length portraiture. Along with other devices specific to the Italian Renaissance such as birth trays (deschi da parto) and wedding chests' decorated panels (cassoni or forzieri), portrait paintings participated to the emphasis on the individual. Portrait paintings were still fashionable during the following centuries and extended to the rising bourgeoisie and eventually to common people, especially during the social and political transformations of the 19th century. At the end of the 19th century and during the 20th century, painted portraits were challenged and eventually supplanted by the development of new media such as photography. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | François Boucher (1703-1770) was born in Paris and probably received his first artistic training from his father who was a painter before attending the Académie de France in Rome. He may also have travelled to Naples, Venice and Bologna. Around 1731 Boucher returned to Paris where he rapidly gained the royal favour and interest from the private collectors. He was a very prolific artist and produced a wide range of artworks from pastoral paintings, porcelain and tapestry designs as well as stage designs influencing deeply the new Rococo movement. This painting is a fine example of the dominant Rococo style in 18th-century France. It depicts the Marquise de Pompadour who became in 1745 the favourite mistress of King Louis XV. She is portrayed in a garden or edges of woods wearing a sumptuous white silk dress which blends in with the ochre green of the vegetation around. This picture is characterised by the combination of a subtle artificiality and sufficient naturalism, which is a typical feature of the Rococo aesthetic. This painting is a good example of how Boucher was probably made to celebrate and consolidate the Marquise’s new status as well as exalting her renowned beauty. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 487-1882 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest