Jug

1842

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The campaign to abolish slavery in Britain began in the 1780s, with the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade holding its first meeting on 22nd May 1787. Between the 1780s and 1860s abolitionists used various means to disseminate their anti-slavery message to British society, not only producing printed pamphlets and books, but also transferring prints and poems onto everyday objects such as textiles and ceramics. By placing anti-slavery imagery onto familiar objects such as jugs, plates and teawares, the abolition movement entered people’s homes and could reach those who were not able to read (the literacy rate in 1820 was 53%). Powerful and provocative yet often problematic images were used to confront the viewer with the plight of enslaved people, evoking sympathy and inviting ethical discussions on the subject of slavery. These images often depicted a kneeling enslaved African in chains, holding their hands out in supplication. The most famous ceramic object to use this motif was the jasperware medallion produced by Josiah Wedgwood and modelled by William Hackwood in 1787, examples of which are in the V&A and V&A Wedgwood Collection. Featuring the imploring inscription ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’, the medallion was reproduced in great numbers and would have been worn by abolitionists as a badge to show their support for the cause.

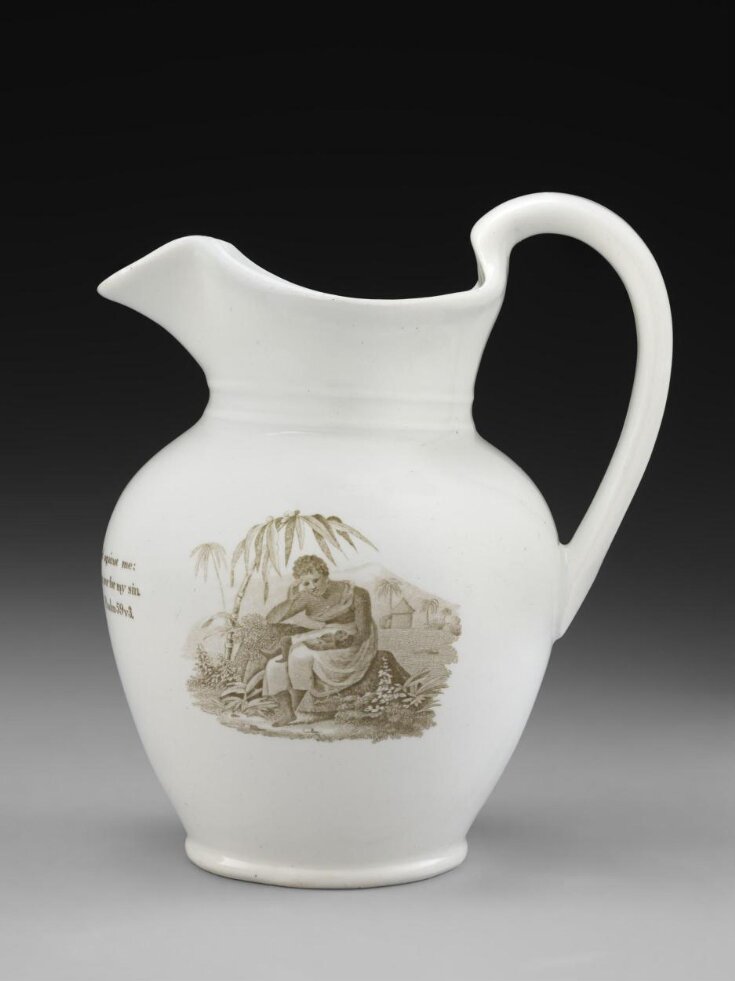

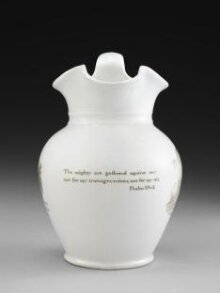

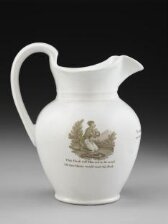

This jug shows how this familiar image was reproduced and repurposed during the abolition movement, in this case as a way to target the sympathies of women. On one side of the jug an enslaved woman is depicted in the same kneeling pose surrounded by chains, yet with her arms holding a Bible to her chest. The inscription below reads ‘This book tell Man not to be cruel, Oh that Massa would read this Book’, demonstrating the belief that slavery was fundamentally opposed to the scriptures and was not aligned with the Christian faith. This is reiterated on the central part of the jug, with an inscription taken from the Bible which reads ‘The mighty are gathered against me: not for my transgressions, nor for my sin. Psalm 59v3’. The other side of the jug uses a print that was commissioned and produced by the Female Society of Birmingham (formerly the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves) in their campaign against slavery. Depicting a distressed woman cradling her child, it was intended to emotionally engage the viewer with the plight of enslaved women, and was used on a variety of objects, such as the silk reticule T.20-1951 in the V&A collection.

The jug was produced by the Minton ceramics factory, identified by the date stamp for 1842 on the base of the jug, the year that Minton first introduced yearly date stamps. It is interesting that objects with such explicit anti-slavery messages were still being produced at this date, after the Abolition acts of 1834 and 1838, when the apprenticeship system was abolished. However the jug may illustrate a continued awareness that slavery had not yet been completely eradicated, as there were still systems of slavery in place in the East India Company territories, Ceylon, and Saint Helena until 1843. The sustained demand for these wares could also have been an example of continued agitation and solidarity with anti-slavery campaigners in the US, and it was possibly made for export.

This jug shows how this familiar image was reproduced and repurposed during the abolition movement, in this case as a way to target the sympathies of women. On one side of the jug an enslaved woman is depicted in the same kneeling pose surrounded by chains, yet with her arms holding a Bible to her chest. The inscription below reads ‘This book tell Man not to be cruel, Oh that Massa would read this Book’, demonstrating the belief that slavery was fundamentally opposed to the scriptures and was not aligned with the Christian faith. This is reiterated on the central part of the jug, with an inscription taken from the Bible which reads ‘The mighty are gathered against me: not for my transgressions, nor for my sin. Psalm 59v3’. The other side of the jug uses a print that was commissioned and produced by the Female Society of Birmingham (formerly the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves) in their campaign against slavery. Depicting a distressed woman cradling her child, it was intended to emotionally engage the viewer with the plight of enslaved women, and was used on a variety of objects, such as the silk reticule T.20-1951 in the V&A collection.

The jug was produced by the Minton ceramics factory, identified by the date stamp for 1842 on the base of the jug, the year that Minton first introduced yearly date stamps. It is interesting that objects with such explicit anti-slavery messages were still being produced at this date, after the Abolition acts of 1834 and 1838, when the apprenticeship system was abolished. However the jug may illustrate a continued awareness that slavery had not yet been completely eradicated, as there were still systems of slavery in place in the East India Company territories, Ceylon, and Saint Helena until 1843. The sustained demand for these wares could also have been an example of continued agitation and solidarity with anti-slavery campaigners in the US, and it was possibly made for export.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Earthenware, transfer-printed and glazed |

| Brief description | Jug, earthenware, with anti-slavery imagery and lines of verse, produced as part of the abolition movement, transfer-printed, made by Minton, England, 1842 |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Summary | The campaign to abolish slavery in Britain began in the 1780s, with the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade holding its first meeting on 22nd May 1787. Between the 1780s and 1860s abolitionists used various means to disseminate their anti-slavery message to British society, not only producing printed pamphlets and books, but also transferring prints and poems onto everyday objects such as textiles and ceramics. By placing anti-slavery imagery onto familiar objects such as jugs, plates and teawares, the abolition movement entered people’s homes and could reach those who were not able to read (the literacy rate in 1820 was 53%). Powerful and provocative yet often problematic images were used to confront the viewer with the plight of enslaved people, evoking sympathy and inviting ethical discussions on the subject of slavery. These images often depicted a kneeling enslaved African in chains, holding their hands out in supplication. The most famous ceramic object to use this motif was the jasperware medallion produced by Josiah Wedgwood and modelled by William Hackwood in 1787, examples of which are in the V&A and V&A Wedgwood Collection. Featuring the imploring inscription ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’, the medallion was reproduced in great numbers and would have been worn by abolitionists as a badge to show their support for the cause. This jug shows how this familiar image was reproduced and repurposed during the abolition movement, in this case as a way to target the sympathies of women. On one side of the jug an enslaved woman is depicted in the same kneeling pose surrounded by chains, yet with her arms holding a Bible to her chest. The inscription below reads ‘This book tell Man not to be cruel, Oh that Massa would read this Book’, demonstrating the belief that slavery was fundamentally opposed to the scriptures and was not aligned with the Christian faith. This is reiterated on the central part of the jug, with an inscription taken from the Bible which reads ‘The mighty are gathered against me: not for my transgressions, nor for my sin. Psalm 59v3’. The other side of the jug uses a print that was commissioned and produced by the Female Society of Birmingham (formerly the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves) in their campaign against slavery. Depicting a distressed woman cradling her child, it was intended to emotionally engage the viewer with the plight of enslaved women, and was used on a variety of objects, such as the silk reticule T.20-1951 in the V&A collection. The jug was produced by the Minton ceramics factory, identified by the date stamp for 1842 on the base of the jug, the year that Minton first introduced yearly date stamps. It is interesting that objects with such explicit anti-slavery messages were still being produced at this date, after the Abolition acts of 1834 and 1838, when the apprenticeship system was abolished. However the jug may illustrate a continued awareness that slavery had not yet been completely eradicated, as there were still systems of slavery in place in the East India Company territories, Ceylon, and Saint Helena until 1843. The sustained demand for these wares could also have been an example of continued agitation and solidarity with anti-slavery campaigners in the US, and it was possibly made for export. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | C.16-2022 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 29, 2022 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest