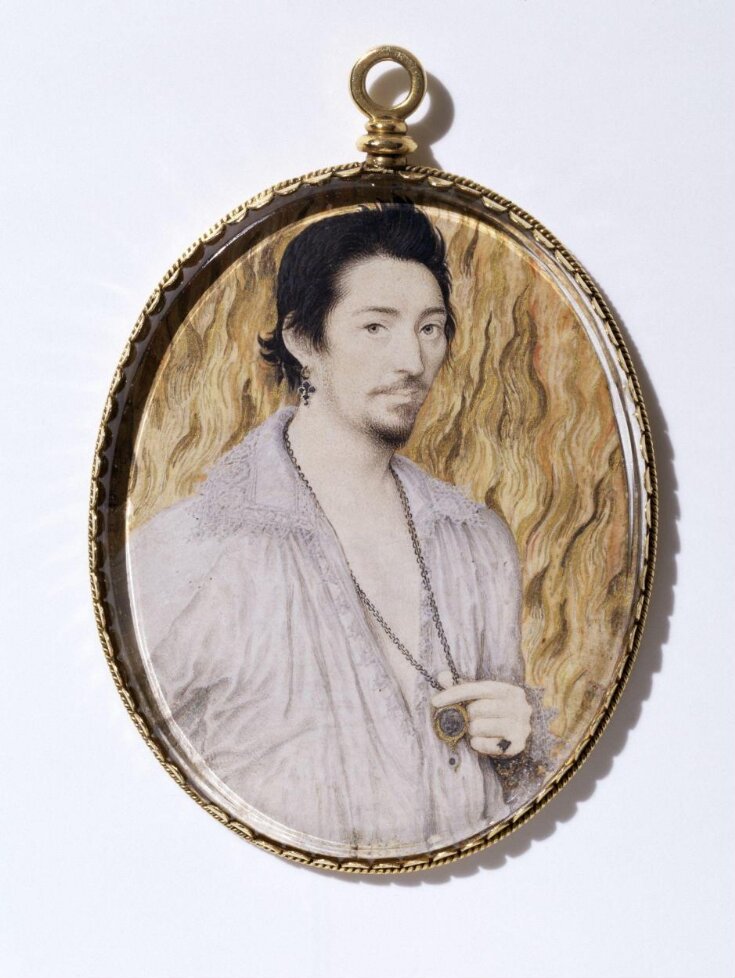

An Unknown Man

Portrait Miniature

ca. 1600 (painted)

ca. 1600 (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

The medium and techniques of miniature painting, or limning as it was traditionally called, developed from the art of illustrating sacred books (also called limning). Nicholas Hilliard first trained as a goldsmith and introduced to this watercolour art innovative techniques for painting gold and jewels. In this miniature we see his characteristic curling and scrolling calligraphy, painted in real gold and then burnished.

Subjects Depicted

This work beautifully illustrates the role of the miniature in the chivalrous atmosphere of dalliance and intrigue at the court of Elizabeth I, where secret gestures of allegiance could become public display depending on the whim of the wearer. Here the young man turns a picture box, the image concealed, towards his heart. This was a gesture of devotion, presumably made to the wearer of his miniature.

Ownership & Use

Unlike large-scale oil paintings, which were painted to be displayed in public rooms, miniatures were usually painted to be worn, to be held, and to be owned by one specific owner. Although we do not know who this miniature was painted for, it is a very intimate image as the gentleman is depicted effectively in a state of undress.

The medium and techniques of miniature painting, or limning as it was traditionally called, developed from the art of illustrating sacred books (also called limning). Nicholas Hilliard first trained as a goldsmith and introduced to this watercolour art innovative techniques for painting gold and jewels. In this miniature we see his characteristic curling and scrolling calligraphy, painted in real gold and then burnished.

Subjects Depicted

This work beautifully illustrates the role of the miniature in the chivalrous atmosphere of dalliance and intrigue at the court of Elizabeth I, where secret gestures of allegiance could become public display depending on the whim of the wearer. Here the young man turns a picture box, the image concealed, towards his heart. This was a gesture of devotion, presumably made to the wearer of his miniature.

Ownership & Use

Unlike large-scale oil paintings, which were painted to be displayed in public rooms, miniatures were usually painted to be worn, to be held, and to be owned by one specific owner. Although we do not know who this miniature was painted for, it is a very intimate image as the gentleman is depicted effectively in a state of undress.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | An Unknown Man (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Watercolour on vellum stuck onto card |

| Brief description | Portrait miniature of an unknown man against a flame background, watercolour on vellum, painted by Nicholas Hilliard, ca. 1600. |

| Physical description | Portrait miniature of a man, oval, half-length, and standing against flames. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Content description | Portrait of a man, half-length, looking to front and holding a pendant, suspended from a chain round his neck, in his right hand; behind him are the flames of a fire. |

| Styles | |

| Gallery label | British Galleries:

Nicholas Hilliard and Miniature Painting Nicholas Hilliard trained as a goldsmith and developed painting techniques that exploited this training. He used metallic pigments to mimic the jewellery on the opulent clothes that were fashionable. Hilliard created the image of Elizabeth and her courtiers that we know today, but he never won a salaried position at court. He had to set up shop in the City of London. From there he painted anyone who could afford his services. The young man clearly intended his portrait to be a very personal gift. He stands dressed only in his shirt, turning a jewel to his heart. The flames almost certainly symbolise passion. (27/03/2003) |

| Credit line | Purchased with the assistance of the Murray Bequest |

| Object history | COLLECTIONS: W.C. Morland of Lamberhurst, Sussex by 1865 when lent to the South Kensington Exhibition as a portrait of Edward Courtney, Earl of Devon; Henry J. P. Pfungst collection; sold Christie’s 14th June 1917 (lot 59); purchased from the funds of the Capt. H. B. Murray Bequest. |

| Production | This miniature was acquired in 1917 as a work attributed to Isaac Oliver. It was reattributed to Nicholas Hilliard in 1943 by Carl Winter. In the 1983 exhibition 'Artists of the Tudor Court' it was attributed to Isaac Oliver by Roy Strong, but in subsequent publications it is still attributed to Nicholas Hilliard. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Object Type The medium and techniques of miniature painting, or limning as it was traditionally called, developed from the art of illustrating sacred books (also called limning). Nicholas Hilliard first trained as a goldsmith and introduced to this watercolour art innovative techniques for painting gold and jewels. In this miniature we see his characteristic curling and scrolling calligraphy, painted in real gold and then burnished. Subjects Depicted This work beautifully illustrates the role of the miniature in the chivalrous atmosphere of dalliance and intrigue at the court of Elizabeth I, where secret gestures of allegiance could become public display depending on the whim of the wearer. Here the young man turns a picture box, the image concealed, towards his heart. This was a gesture of devotion, presumably made to the wearer of his miniature. Ownership & Use Unlike large-scale oil paintings, which were painted to be displayed in public rooms, miniatures were usually painted to be worn, to be held, and to be owned by one specific owner. Although we do not know who this miniature was painted for, it is a very intimate image as the gentleman is depicted effectively in a state of undress. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | P.5-1917 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest