I Still Believe in Our City

Poster

2020

2020

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

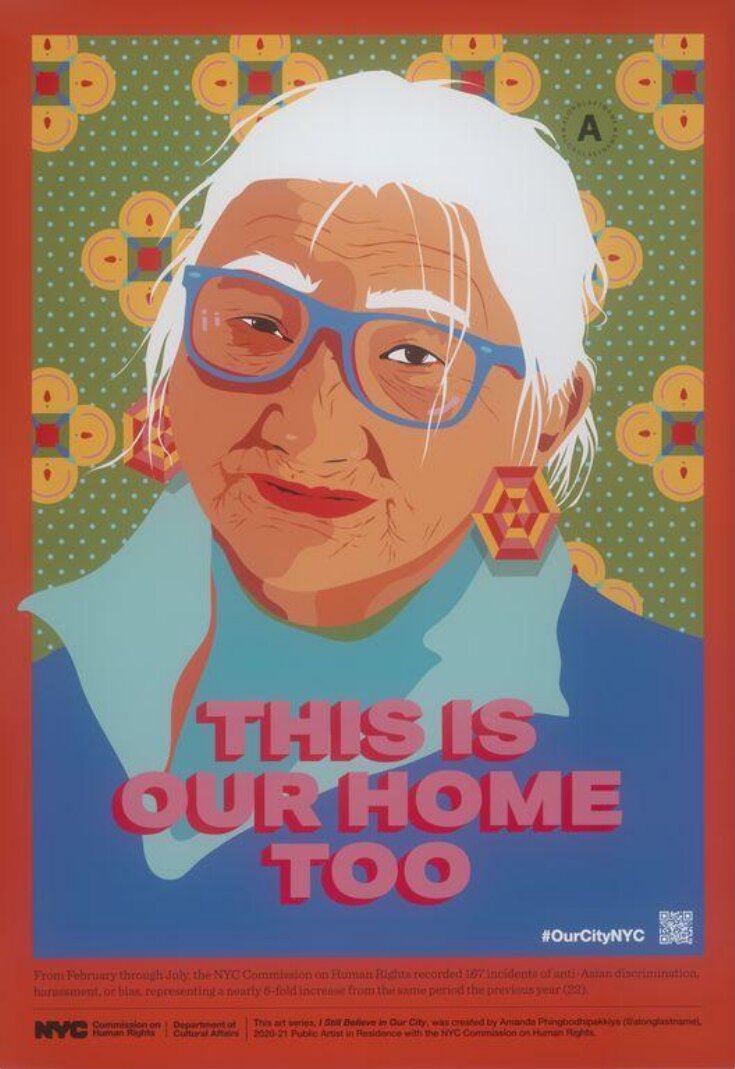

This poster is one of a series of five posters from Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya’s 2020 I Still Believe In Our City project. The project was the artist’s response to the growing racism towards Asian and Pacific Islanders (API) in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic. The five posters are designed for NYC bus shelters, each featuring a portrait of an Asian and Pacific Island individual alongside the anti-discriminatory messages: ‘I am not your scapegoat’, ‘I still believe in our city’, ‘This is our home too’, ‘I did not make you sick’, ‘We belong here’.

Phingbodhipakkiya explains the background behind the commission, and its outcomes:

“In February 2020, I went to Chinatown in Manhattan to get groceries. A familiar weekend ritual. But instead of the hustle and bustle, the noise, the chaos, the delightful vibrance, it was quiet. Unsettlingly quiet. A deep sense of foreboding loomed as I went about my shopping.

News outlets were reporting that a dangerous new flu-like virus, first spotted in Wuhan, China, had made its way to the US. And just like that, Chinatown had cleared out. Would there be more racism and xenophobia ahead for my people?

I soon found out. Reports of attacks on Asian Americans across the United States and around the world filled my feed. Yet few media outlets were covering it. In the days before New York City locked down, I got on the subway and a man next to me seethed, “Ew, gross” and fled to the other side of the subway car. I was stunned. A few days later, my parents were yelled at in a grocery store to “Go back to where they came from”. It broke my heart.

I wrote in my journal, trying to process what had happened. I didn’t know it then, but those words would soon appear in the art all over the city.”

In April of 2020, I saw that the NYC Commission on Human Rights had put out an open call for an artist-in-residence position. I applied immediately. Partnering with the agency tasked with upholding the City’s human rights laws, we could issue a bold, visible rebuke of this violence and harassment. But by late May, I hadn't heard back. I started to lose hope. Maybe the city would overlook our struggle. But just as I was processing the news of an Asian grandmother

being set on fire, I got the call.

The artist-in-residence program team had given us a schedule to follow. The actual making of art wasn’t on the agenda until early 2021. But there was no time to waste.

In my first meeting with the Commissioner, I shared my vision for a city-wide public art campaign dedicated to the Asian American community. She was immediately onboard. I decided that I didn’t need anyone’s permission to speak up for my community. A single installation wouldn't do. I needed Asian Americans across each of the five boroughs to know that they belonged and that the City was behind them. We would not take this hate lying down.

I met with community leaders and advocates, listening to their stories, their worries, their hopes. What emerged was over 100 works dispersed around New York City. This included a portrait series of intergenerational guardians defiantly declaring our belonging, splashed across 76 bus shelters around NYC selected for their proximity to anti-Asian bias incidents.

In each face, a loving compilation of myself, my friends, family and the community members. I wanted them to feel familiar. They could have been the daughter who was jeered and cursed at, the uncle who was shoved and spat on, the grandmother who was hit in the face. But instead of seeming afraid or upset, these guardians stood tall and proud. People tell me that seeing these defiant Asian faces makes them feel safe. It makes them feel like there’s room here for Asian American voices, journeys and dreams.

Millions of my Asian brothers and sisters have found peace and pride in my artwork. It’s found its way on the sides of buildings, on magazine covers, bus shelters and cultural centers. It’s a humbling and nearly unfathomable thought.

Art has the ability to soothe grief, amplify joy, and drive people to action. I want my art to do that. I want it to invite allies to stand with us. I want it to be a rallying cry to keep fighting for systematic change, more resources for our communities and our shared futures.

I Still Believe in Our City is a vibrant reminder of the beauty and resilience of our people. We have been here and we are not going anywhere. We are here to speak. We are here to stand. We are here to stay.”

Phingbodhipakkiya explains the background behind the commission, and its outcomes:

“In February 2020, I went to Chinatown in Manhattan to get groceries. A familiar weekend ritual. But instead of the hustle and bustle, the noise, the chaos, the delightful vibrance, it was quiet. Unsettlingly quiet. A deep sense of foreboding loomed as I went about my shopping.

News outlets were reporting that a dangerous new flu-like virus, first spotted in Wuhan, China, had made its way to the US. And just like that, Chinatown had cleared out. Would there be more racism and xenophobia ahead for my people?

I soon found out. Reports of attacks on Asian Americans across the United States and around the world filled my feed. Yet few media outlets were covering it. In the days before New York City locked down, I got on the subway and a man next to me seethed, “Ew, gross” and fled to the other side of the subway car. I was stunned. A few days later, my parents were yelled at in a grocery store to “Go back to where they came from”. It broke my heart.

I wrote in my journal, trying to process what had happened. I didn’t know it then, but those words would soon appear in the art all over the city.”

In April of 2020, I saw that the NYC Commission on Human Rights had put out an open call for an artist-in-residence position. I applied immediately. Partnering with the agency tasked with upholding the City’s human rights laws, we could issue a bold, visible rebuke of this violence and harassment. But by late May, I hadn't heard back. I started to lose hope. Maybe the city would overlook our struggle. But just as I was processing the news of an Asian grandmother

being set on fire, I got the call.

The artist-in-residence program team had given us a schedule to follow. The actual making of art wasn’t on the agenda until early 2021. But there was no time to waste.

In my first meeting with the Commissioner, I shared my vision for a city-wide public art campaign dedicated to the Asian American community. She was immediately onboard. I decided that I didn’t need anyone’s permission to speak up for my community. A single installation wouldn't do. I needed Asian Americans across each of the five boroughs to know that they belonged and that the City was behind them. We would not take this hate lying down.

I met with community leaders and advocates, listening to their stories, their worries, their hopes. What emerged was over 100 works dispersed around New York City. This included a portrait series of intergenerational guardians defiantly declaring our belonging, splashed across 76 bus shelters around NYC selected for their proximity to anti-Asian bias incidents.

In each face, a loving compilation of myself, my friends, family and the community members. I wanted them to feel familiar. They could have been the daughter who was jeered and cursed at, the uncle who was shoved and spat on, the grandmother who was hit in the face. But instead of seeming afraid or upset, these guardians stood tall and proud. People tell me that seeing these defiant Asian faces makes them feel safe. It makes them feel like there’s room here for Asian American voices, journeys and dreams.

Millions of my Asian brothers and sisters have found peace and pride in my artwork. It’s found its way on the sides of buildings, on magazine covers, bus shelters and cultural centers. It’s a humbling and nearly unfathomable thought.

Art has the ability to soothe grief, amplify joy, and drive people to action. I want my art to do that. I want it to invite allies to stand with us. I want it to be a rallying cry to keep fighting for systematic change, more resources for our communities and our shared futures.

I Still Believe in Our City is a vibrant reminder of the beauty and resilience of our people. We have been here and we are not going anywhere. We are here to speak. We are here to stand. We are here to stay.”

Delve deeper

Discover more about this object

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | I Still Believe in Our City (assigned by artist) |

| Materials and techniques | Printed on a cannon 12 colour digital press, paper stock 200gsm photographic satin finish. |

| Brief description | 'I Still Believe in Our City' public art campaign posters, commissioned by the New York City Commission on Human Rights as part of the Public Artist in Residence programme, designed by Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, 2020. |

| Physical description | A poster with artwork with bright colours and bold design showing an Asian and Pacific Islander. In large font, across the portrait, there is the message ‘This is our home too’. In smaller font at the bottom of the poster, there is further information about how anti-Asian discrimination has increased during the Covid-19 pandemic. There is also the logo for the Comission on Human rights, a QR code, and the hashtag #OurCityNYC. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Production type | Design |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Commissioned by the City of New York's Commission on Human Rights and Department of Cultural Affairs |

| Production | Printed in London by Complete Ltd. |

| Summary | This poster is one of a series of five posters from Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya’s 2020 I Still Believe In Our City project. The project was the artist’s response to the growing racism towards Asian and Pacific Islanders (API) in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic. The five posters are designed for NYC bus shelters, each featuring a portrait of an Asian and Pacific Island individual alongside the anti-discriminatory messages: ‘I am not your scapegoat’, ‘I still believe in our city’, ‘This is our home too’, ‘I did not make you sick’, ‘We belong here’. Phingbodhipakkiya explains the background behind the commission, and its outcomes: “In February 2020, I went to Chinatown in Manhattan to get groceries. A familiar weekend ritual. But instead of the hustle and bustle, the noise, the chaos, the delightful vibrance, it was quiet. Unsettlingly quiet. A deep sense of foreboding loomed as I went about my shopping. News outlets were reporting that a dangerous new flu-like virus, first spotted in Wuhan, China, had made its way to the US. And just like that, Chinatown had cleared out. Would there be more racism and xenophobia ahead for my people? I soon found out. Reports of attacks on Asian Americans across the United States and around the world filled my feed. Yet few media outlets were covering it. In the days before New York City locked down, I got on the subway and a man next to me seethed, “Ew, gross” and fled to the other side of the subway car. I was stunned. A few days later, my parents were yelled at in a grocery store to “Go back to where they came from”. It broke my heart. I wrote in my journal, trying to process what had happened. I didn’t know it then, but those words would soon appear in the art all over the city.” In April of 2020, I saw that the NYC Commission on Human Rights had put out an open call for an artist-in-residence position. I applied immediately. Partnering with the agency tasked with upholding the City’s human rights laws, we could issue a bold, visible rebuke of this violence and harassment. But by late May, I hadn't heard back. I started to lose hope. Maybe the city would overlook our struggle. But just as I was processing the news of an Asian grandmother being set on fire, I got the call. The artist-in-residence program team had given us a schedule to follow. The actual making of art wasn’t on the agenda until early 2021. But there was no time to waste. In my first meeting with the Commissioner, I shared my vision for a city-wide public art campaign dedicated to the Asian American community. She was immediately onboard. I decided that I didn’t need anyone’s permission to speak up for my community. A single installation wouldn't do. I needed Asian Americans across each of the five boroughs to know that they belonged and that the City was behind them. We would not take this hate lying down. I met with community leaders and advocates, listening to their stories, their worries, their hopes. What emerged was over 100 works dispersed around New York City. This included a portrait series of intergenerational guardians defiantly declaring our belonging, splashed across 76 bus shelters around NYC selected for their proximity to anti-Asian bias incidents. In each face, a loving compilation of myself, my friends, family and the community members. I wanted them to feel familiar. They could have been the daughter who was jeered and cursed at, the uncle who was shoved and spat on, the grandmother who was hit in the face. But instead of seeming afraid or upset, these guardians stood tall and proud. People tell me that seeing these defiant Asian faces makes them feel safe. It makes them feel like there’s room here for Asian American voices, journeys and dreams. Millions of my Asian brothers and sisters have found peace and pride in my artwork. It’s found its way on the sides of buildings, on magazine covers, bus shelters and cultural centers. It’s a humbling and nearly unfathomable thought. Art has the ability to soothe grief, amplify joy, and drive people to action. I want my art to do that. I want it to invite allies to stand with us. I want it to be a rallying cry to keep fighting for systematic change, more resources for our communities and our shared futures. I Still Believe in Our City is a vibrant reminder of the beauty and resilience of our people. We have been here and we are not going anywhere. We are here to speak. We are here to stand. We are here to stay.” |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | CD.47-2021 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 2, 2021 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSON