Workbox

ca. 1850 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Jennens & Bettridge, whose name is stamped on this work basket, were one of the largest and most prominent firms of papier-mâché manufacturers in Birmingham. In 1815 Theodore Hyla Jennens and John Bettridge took over an existing factory at 99, Constitution Hill and subsequently opened a London showroom at 6 Halkin Street West, Belgrave Square. The firm produced a wide range of papier-mâché goods ranging in size and complexity from small trays and boxes to large pieces of furniture such as beds and pianos, some of which were displayed in their stand at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

This work basket is typical of the small domestic products made of papier-mâché. It was made in sections by placing layers of paper, pasted on both sides, over moulds of the right shape. This part of the work was usually carried out by women and girls. After the box had been dried in a stove, oiled and dried again, a cabinet-maker was responsible for removing the parts of the box from the moulds, assembling it, and for any necessary planing, filing or smoothing, before the layers of black and clear varnish, painted decoration and gilding were added in the paint shop. Before and after each layer of varnish or decoration the work basket was stove dried. Fittings, like the handle, were added, before the box was given a final polish.

This work basket is typical of the small domestic products made of papier-mâché. It was made in sections by placing layers of paper, pasted on both sides, over moulds of the right shape. This part of the work was usually carried out by women and girls. After the box had been dried in a stove, oiled and dried again, a cabinet-maker was responsible for removing the parts of the box from the moulds, assembling it, and for any necessary planing, filing or smoothing, before the layers of black and clear varnish, painted decoration and gilding were added in the paint shop. Before and after each layer of varnish or decoration the work basket was stove dried. Fittings, like the handle, were added, before the box was given a final polish.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Papier-mâché with watered silk lining |

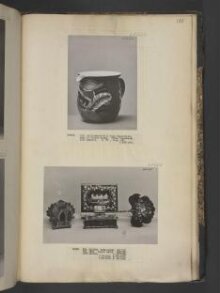

| Brief description | Workbox of papier-mâché, with painted decoration and gilding, by Jennens & Bettridge. England, ca. 1850. |

| Physical description | Papier-mâché box in the form of a basket with two sloping lids and an arched handle, painted with gold and floral designs on a black ground. The signature of the maker is impressed. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | Jennens & Bettridge, whose name is stamped on this work basket, were one of the largest and most prominent firms of papier-mâché manufacturers in Birmingham. In 1815 Theodore Hyla Jennens and John Bettridge took over an existing factory at 99, Constitution Hill and subsequently opened a London showroom at 6 Halkin Street West, Belgrave Square. The firm produced a wide range of papier-mâché goods ranging in size and complexity from small trays and boxes to large pieces of furniture such as beds and pianos, some of which were displayed in their stand at the Great Exhibition of 1851. This work basket is typical of the small domestic products made of papier-mâché. It was made in sections by placing layers of paper, pasted on both sides, over moulds of the right shape. This part of the work was usually carried out by women and girls. After the box had been dried in a stove, oiled and dried again, a cabinet-maker was responsible for removing the parts of the box from the moulds, assembling it, and for any necessary planing, filing or smoothing, before the layers of black and clear varnish, painted decoration and gilding were added in the paint shop. Before and after each layer of varnish or decoration the work basket was stove dried. Fittings, like the handle, were added, before the box was given a final polish. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.150-1919 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest