The apotheosis of Homer

Book

1849 (published)

1849 (published)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

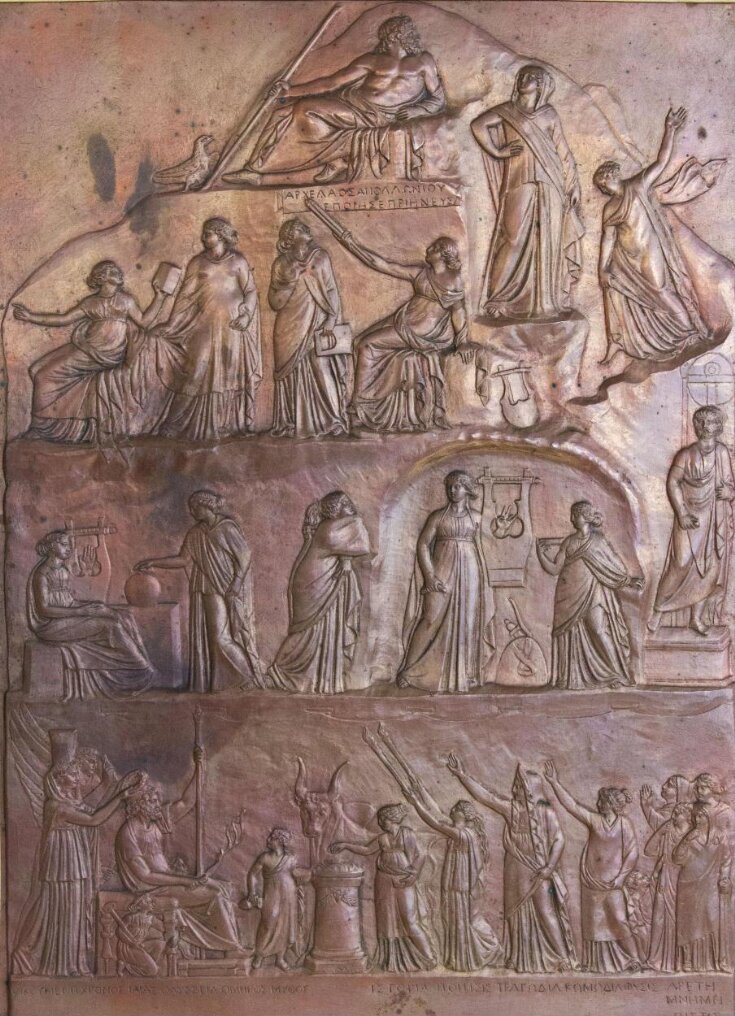

This publication contains an essay on a classical relief in the British Museum ('The Apotheosis of Homer') written by the eminent German archaeologist, August Emil Braun (1809-56). The original sculptural relief is a 3rd-century, marble depicting gods, muses, Homeric characters and worshippers honouring the poet, who was venerated as a hero in classical Greece. It was published by the pioneering metal manufacturers, Elkington & Co. of Birmingham and London. Inside the back cover is a copper electrotype reduction of the relief made using Elkington's pioneering electroforming technology. The publication is dated 1849, two years before Elkington's electrotypes caused a sensation at the Great Exhibition of 1851 making the relief an early and rare example of the technology.

A note in pencil on the title page - 'Mrs Ashton from the author' - suggests the book was not only a gift from Braun, but that most likely recipient was Elizabeth Gair Ashton (1831-1914), wife of Thomas Ashton (1818-1898), Manchester cotton mill owner, philanthropist, educationalist, art collector, social reformer and politician. He was on the Executive Committee of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857 and gave £1000 towards it. He studied chemistry and printing techniques at the University of Heidelberg in the 1830s giving the production of a publication with an electrotype reproduction inside the back cover a particular resonance. Elizabeth was the daughter of Samuel Stillman Gair (1789-1847), originally of Boston, Massachusetts, who was also involved in both the cotton trade and banking. He founded the branch of Baring's Bank in Liverpool. The social, political and industrial milieu from which this publication emerges therefore sits at the intersection of art education, archaeology, science, manufacturing, new patronage, social reform and exhibition. Ashton had a reputation among his workers for fair treatment and of offering strong support for their educational and moral welfare. Like many civic figures in the 19th century, he presents a complex mix. Underpinning this wealth was also cotton from American slave plantations.

Emil Braun travelled throughout Europe collecting artworks and in 1849 became Secretary to the Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut in Rome. In 1854 he published The Ruins and Museums of Rome which was dedicated, 'To the English Visitors in Rome.' One of those had been Prince Albert (1819-61) in 1838. When Albert toured Rome, Braun acted as his guide and had a strong influence developing Albert's interest in art and architecture.

Braun supplied a number of artists and metalworkers with plaster moulds taken from classical reliefs and Renaissance artworks throughout the 1840s, including Elkington who published this volume. The Elkington business archive, which is in the V&A's Archive of Art and Design, contains a ledger listing the models he supplied them including this subject ('61. The Apotheosis of Homer reduced from the marble in British Museum, 18 shillings'). Much of Elkington's stand at the 1849 Birmingham Exhibition, and later in the Great Exhibition, was made up of early electro-deposits from moulds supplied by Braun. Contemporaries recognised Elkington's electrotypes for 'the important position they promise to take in the progress of Art-education' (Robert Hunt, 'The British Association Meeting at Birmingham, and the Exhibition of Manufactures and Art', The Art-Journal, Vol.11 (1849), pp 335-6).

The original sculptural relief is a 3rd-century, marble depicting gods, muses, Homeric characters and worshippers honouring the poet, who was venerated as a hero in classical Greece. This reproduction is a good reminder of the remaining prevalence of classicism in art education in the mid-19th-century, something often overlooked given the attention afforded to the Gothic and Renaissance revivals. The first electro-deposits were largely classically inspired and it really only from after 1851 that their outlook diversifies. So this volume and its electrotype relief capture a moment in art history where change is about to occur: the relief depicts the prevailing orthodoxy of art education but its method of production signals that a whole range of other sources is about to be made available to the art world, led to a great extent by the South Kensington Museum, where numerous electrotypes entered the collections, for public display as well as student study, and were also offered for sale.

A note in pencil on the title page - 'Mrs Ashton from the author' - suggests the book was not only a gift from Braun, but that most likely recipient was Elizabeth Gair Ashton (1831-1914), wife of Thomas Ashton (1818-1898), Manchester cotton mill owner, philanthropist, educationalist, art collector, social reformer and politician. He was on the Executive Committee of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857 and gave £1000 towards it. He studied chemistry and printing techniques at the University of Heidelberg in the 1830s giving the production of a publication with an electrotype reproduction inside the back cover a particular resonance. Elizabeth was the daughter of Samuel Stillman Gair (1789-1847), originally of Boston, Massachusetts, who was also involved in both the cotton trade and banking. He founded the branch of Baring's Bank in Liverpool. The social, political and industrial milieu from which this publication emerges therefore sits at the intersection of art education, archaeology, science, manufacturing, new patronage, social reform and exhibition. Ashton had a reputation among his workers for fair treatment and of offering strong support for their educational and moral welfare. Like many civic figures in the 19th century, he presents a complex mix. Underpinning this wealth was also cotton from American slave plantations.

Emil Braun travelled throughout Europe collecting artworks and in 1849 became Secretary to the Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut in Rome. In 1854 he published The Ruins and Museums of Rome which was dedicated, 'To the English Visitors in Rome.' One of those had been Prince Albert (1819-61) in 1838. When Albert toured Rome, Braun acted as his guide and had a strong influence developing Albert's interest in art and architecture.

Braun supplied a number of artists and metalworkers with plaster moulds taken from classical reliefs and Renaissance artworks throughout the 1840s, including Elkington who published this volume. The Elkington business archive, which is in the V&A's Archive of Art and Design, contains a ledger listing the models he supplied them including this subject ('61. The Apotheosis of Homer reduced from the marble in British Museum, 18 shillings'). Much of Elkington's stand at the 1849 Birmingham Exhibition, and later in the Great Exhibition, was made up of early electro-deposits from moulds supplied by Braun. Contemporaries recognised Elkington's electrotypes for 'the important position they promise to take in the progress of Art-education' (Robert Hunt, 'The British Association Meeting at Birmingham, and the Exhibition of Manufactures and Art', The Art-Journal, Vol.11 (1849), pp 335-6).

The original sculptural relief is a 3rd-century, marble depicting gods, muses, Homeric characters and worshippers honouring the poet, who was venerated as a hero in classical Greece. This reproduction is a good reminder of the remaining prevalence of classicism in art education in the mid-19th-century, something often overlooked given the attention afforded to the Gothic and Renaissance revivals. The first electro-deposits were largely classically inspired and it really only from after 1851 that their outlook diversifies. So this volume and its electrotype relief capture a moment in art history where change is about to occur: the relief depicts the prevailing orthodoxy of art education but its method of production signals that a whole range of other sources is about to be made available to the art world, led to a great extent by the South Kensington Museum, where numerous electrotypes entered the collections, for public display as well as student study, and were also offered for sale.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The apotheosis of Homer (published title) |

| Materials and techniques | |

| Brief description | Book, The apotheosis of Homer. An electrotype from the celebrated original bas-relief preserved in the British Museum, with a descriptive elucidation by Emile Braun, London: Published by H. Elkington and Co, London and Birmingham and Thomas McLean, 26 Haymarket, London, 1849. |

| Physical description | 10 pages, with a copper electrotype reduction of the marble relief inside the back cover; original cloth binding rubbed, spine missing. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Content description | Essay by Emile Braun on the Apotheosis of Homer marble relief in the British Museum with an electrotype reduction of the relief mounted inside the back cover. |

| Style | |

| Production type | Limited edition |

| Object history | Given by the author, Emile Braun (also spelt Emil), to Elizabeth Gair Ashton (1831-1914), wife of Thomas Ashton (1818-1898), Manchester cotton mill owner, philanthropist, educationalist, art collector, social reformer and politician: note in pencil on the title page 'Mrs Ashton from the author'. Purchased in 2020 by the Museum from Nicholas Bernstein, bookseller, London. |

| Historical context | Electrotypes were a by-product of the invention of electroplating - plating with metals using an electric current (electrolysis). The invention of electrolysis was the first time matter could be manipulated at a molecular level. Developed commercially by the metals manufacturers, Elkington and Co., of Birmingham, who patenetd the process in 1840, it was first applied to the making of art, luxury and educational works. Collaterial industries that developed from the technology, or off-shoots of it, were the manufacture of electrical wire (upon which the electrical revolution depended) and the plastics industry. Modern day nanotechnology is the direct descendent of electroforming and electrotyping. ELECTROPLATING: A negatively charged silver bar, suspended in a vat of potassium cyanide, deposits a coating of metal on a positively charged base metal (mostly copper, later nickel-silver) object immersed with it. Electroplated objects were fully formed in base metal before plating. ELECTROGILDING exploited the same technique but used gold bars instead of silver. It was safer than traditional mercury gilding. ELECTROFORMING transferred the metal deposits directly into moulds in the plating vats. When enough metal had been deposited to create a self-supporting object the mould was removed. Developed by Alexander Parkes, electroforms so accurately mirrored the moulds in which they were created that multiple copies could be created (ELECTROTYPES). The Process During the electrotyping process a mould was taken of the original object. The moulds were made from gutta percha or plaster. Gutta percha was a tree-resin from Malaysia that could be melted and poured onto an object, but would set hard and take a perfect impression. During cooling it could also be manipulated. When the mould set, it was removed from the original object and then lined with graphite or plumbago to make it conductive. This mould was then immersed in the plating vats for coating with copper. |

| Association | |

| Summary | This publication contains an essay on a classical relief in the British Museum ('The Apotheosis of Homer') written by the eminent German archaeologist, August Emil Braun (1809-56). The original sculptural relief is a 3rd-century, marble depicting gods, muses, Homeric characters and worshippers honouring the poet, who was venerated as a hero in classical Greece. It was published by the pioneering metal manufacturers, Elkington & Co. of Birmingham and London. Inside the back cover is a copper electrotype reduction of the relief made using Elkington's pioneering electroforming technology. The publication is dated 1849, two years before Elkington's electrotypes caused a sensation at the Great Exhibition of 1851 making the relief an early and rare example of the technology. A note in pencil on the title page - 'Mrs Ashton from the author' - suggests the book was not only a gift from Braun, but that most likely recipient was Elizabeth Gair Ashton (1831-1914), wife of Thomas Ashton (1818-1898), Manchester cotton mill owner, philanthropist, educationalist, art collector, social reformer and politician. He was on the Executive Committee of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857 and gave £1000 towards it. He studied chemistry and printing techniques at the University of Heidelberg in the 1830s giving the production of a publication with an electrotype reproduction inside the back cover a particular resonance. Elizabeth was the daughter of Samuel Stillman Gair (1789-1847), originally of Boston, Massachusetts, who was also involved in both the cotton trade and banking. He founded the branch of Baring's Bank in Liverpool. The social, political and industrial milieu from which this publication emerges therefore sits at the intersection of art education, archaeology, science, manufacturing, new patronage, social reform and exhibition. Ashton had a reputation among his workers for fair treatment and of offering strong support for their educational and moral welfare. Like many civic figures in the 19th century, he presents a complex mix. Underpinning this wealth was also cotton from American slave plantations. Emil Braun travelled throughout Europe collecting artworks and in 1849 became Secretary to the Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut in Rome. In 1854 he published The Ruins and Museums of Rome which was dedicated, 'To the English Visitors in Rome.' One of those had been Prince Albert (1819-61) in 1838. When Albert toured Rome, Braun acted as his guide and had a strong influence developing Albert's interest in art and architecture. Braun supplied a number of artists and metalworkers with plaster moulds taken from classical reliefs and Renaissance artworks throughout the 1840s, including Elkington who published this volume. The Elkington business archive, which is in the V&A's Archive of Art and Design, contains a ledger listing the models he supplied them including this subject ('61. The Apotheosis of Homer reduced from the marble in British Museum, 18 shillings'). Much of Elkington's stand at the 1849 Birmingham Exhibition, and later in the Great Exhibition, was made up of early electro-deposits from moulds supplied by Braun. Contemporaries recognised Elkington's electrotypes for 'the important position they promise to take in the progress of Art-education' (Robert Hunt, 'The British Association Meeting at Birmingham, and the Exhibition of Manufactures and Art', The Art-Journal, Vol.11 (1849), pp 335-6). The original sculptural relief is a 3rd-century, marble depicting gods, muses, Homeric characters and worshippers honouring the poet, who was venerated as a hero in classical Greece. This reproduction is a good reminder of the remaining prevalence of classicism in art education in the mid-19th-century, something often overlooked given the attention afforded to the Gothic and Renaissance revivals. The first electro-deposits were largely classically inspired and it really only from after 1851 that their outlook diversifies. So this volume and its electrotype relief capture a moment in art history where change is about to occur: the relief depicts the prevailing orthodoxy of art education but its method of production signals that a whole range of other sources is about to be made available to the art world, led to a great extent by the South Kensington Museum, where numerous electrotypes entered the collections, for public display as well as student study, and were also offered for sale. |

| Bibliographic reference | Alistair Grant and Angus Patterson, The Museum and the Factory: The V&A, Elkington and the Electrical Revolution, V&A/Lund Humphies, 2018

(For explanation of history and cultural legacy of the technology and the circumstances around which it caused a sensation at the Great Exhibition, 2 years after the production of this work.) |

| Other number | 2020/84 - RF number |

| Collection | |

| Library number | 38041020004099 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | January 28, 2020 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest