reliquary

Reliquary

1300-1325

1300-1325

| Place of origin |

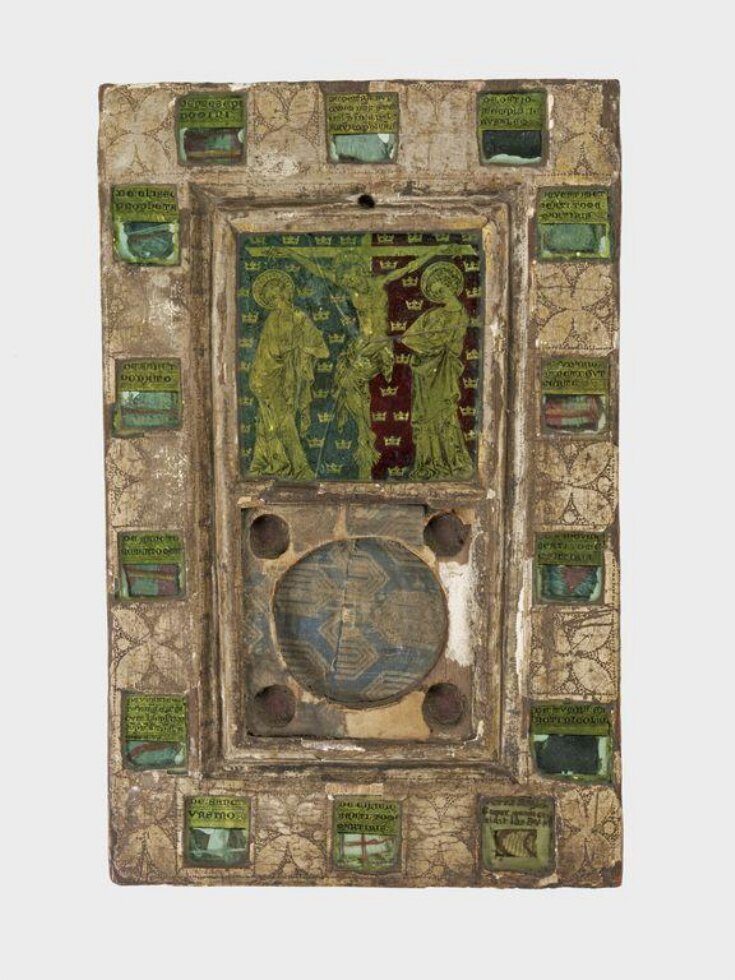

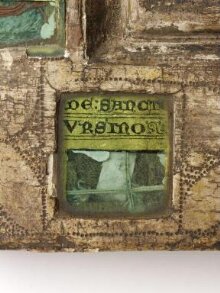

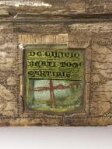

Relics, from the Latin for 'remains' or 'things left behind', are the physical remains of a saint. They can also be the saint's clothing, his or her possessions, and anything else which has come into contact with the saint's body, such as furniture or floor tiles. Relics are holy and transmit their spiritual power to people or things that are in close proximity to them. 'Those who touch the bones of the martyrs participate in their sanctity', wrote Basil, Bishop of Caesaria (now Kaisarieh, modern Turkey) in the late fourth century. Gazing upon relics was also a way of receiving their power, and the devout Christians contemplating this panel would have benefited from the divine protection emitted by the relics set around the scene of the Crucifixion. These include a splinter from Christ's crib, fragments from the stone on which He stood when He preached to the crowds in Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, and some earth which absorbed a drop of His mother's milk. This reliquary may have been commissioned by the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, one of the wealthiest in England at the time. The crowns on a red and blue field behind the central crucifixion scene recall the abbey’s arms and those of its patron saint, Edmund, King of East Anglia, martyred by Vikings in 869. The English identity of the reliquary patrons is confirmed by the striking number of relics of English saints: two fragments of Archbishop Thomas Becket's vestments (martyred 1170) and a drop of his blood, as well as an unspecified relic of the child martyr Robert (allegedly crucified in bury St Edmunds in 1181). Ursin, Bishop of Bourges, is a fourth century French saint who was supposedly present at Christ's Last Supper before His trial and crucifixion. Ursin is rarely commemorated in England, but he was celebrated at Malmesbury in the early fourteenth century, and as someone who witnessed the final days of Christ, he would be an appropriate saint to include in a reliquary with a central scene of the Crucifixion.

The place where the reliquary was made, however, is difficult to establish. The way the Crucifixion scene is painted suggests a French artist, but the technique of gilded and painted glass is particularly associated with Italy during this period. The painter Cennino Cennini (d. Florence, around 1440) refers to the technique in his treatise on painting, written around 1390, and explains that it is 'indescribably attractive, fine and unusual, and this is a branch of great piety, for the embellishment of holy reliquaries'. It may be that the verre eglomisé elements were commissioned abroad and mounted in England.

The place where the reliquary was made, however, is difficult to establish. The way the Crucifixion scene is painted suggests a French artist, but the technique of gilded and painted glass is particularly associated with Italy during this period. The painter Cennino Cennini (d. Florence, around 1440) refers to the technique in his treatise on painting, written around 1390, and explains that it is 'indescribably attractive, fine and unusual, and this is a branch of great piety, for the embellishment of holy reliquaries'. It may be that the verre eglomisé elements were commissioned abroad and mounted in England.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | reliquary (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | |

| Brief description | rectangular panel, wood, with gesso, gilding and textile, set with gilded glass (verre eglomisé) painted with a scene of the Crucifixion, and with smaller panels under which are relics wrapped in cloth. |

| Physical description | Rectangular panel, with fourteen textile-wrapped relics set under painted and gilded glass around the edge, and an image of the Crucifixion in painted and gilded glass in the centre. Below the Crucifixion scene there is a circular socket lined with textile, surrounded by four smaller round ones, which may originally have held another painted scene and relics. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Lent by Douai Abbey. |

| Summary | Relics, from the Latin for 'remains' or 'things left behind', are the physical remains of a saint. They can also be the saint's clothing, his or her possessions, and anything else which has come into contact with the saint's body, such as furniture or floor tiles. Relics are holy and transmit their spiritual power to people or things that are in close proximity to them. 'Those who touch the bones of the martyrs participate in their sanctity', wrote Basil, Bishop of Caesaria (now Kaisarieh, modern Turkey) in the late fourth century. Gazing upon relics was also a way of receiving their power, and the devout Christians contemplating this panel would have benefited from the divine protection emitted by the relics set around the scene of the Crucifixion. These include a splinter from Christ's crib, fragments from the stone on which He stood when He preached to the crowds in Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, and some earth which absorbed a drop of His mother's milk. This reliquary may have been commissioned by the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, one of the wealthiest in England at the time. The crowns on a red and blue field behind the central crucifixion scene recall the abbey’s arms and those of its patron saint, Edmund, King of East Anglia, martyred by Vikings in 869. The English identity of the reliquary patrons is confirmed by the striking number of relics of English saints: two fragments of Archbishop Thomas Becket's vestments (martyred 1170) and a drop of his blood, as well as an unspecified relic of the child martyr Robert (allegedly crucified in bury St Edmunds in 1181). Ursin, Bishop of Bourges, is a fourth century French saint who was supposedly present at Christ's Last Supper before His trial and crucifixion. Ursin is rarely commemorated in England, but he was celebrated at Malmesbury in the early fourteenth century, and as someone who witnessed the final days of Christ, he would be an appropriate saint to include in a reliquary with a central scene of the Crucifixion. The place where the reliquary was made, however, is difficult to establish. The way the Crucifixion scene is painted suggests a French artist, but the technique of gilded and painted glass is particularly associated with Italy during this period. The painter Cennino Cennini (d. Florence, around 1440) refers to the technique in his treatise on painting, written around 1390, and explains that it is 'indescribably attractive, fine and unusual, and this is a branch of great piety, for the embellishment of holy reliquaries'. It may be that the verre eglomisé elements were commissioned abroad and mounted in England. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | LOAN:MET.1-2019 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | April 1, 2019 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSON