Woven Silk

1475-1500 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

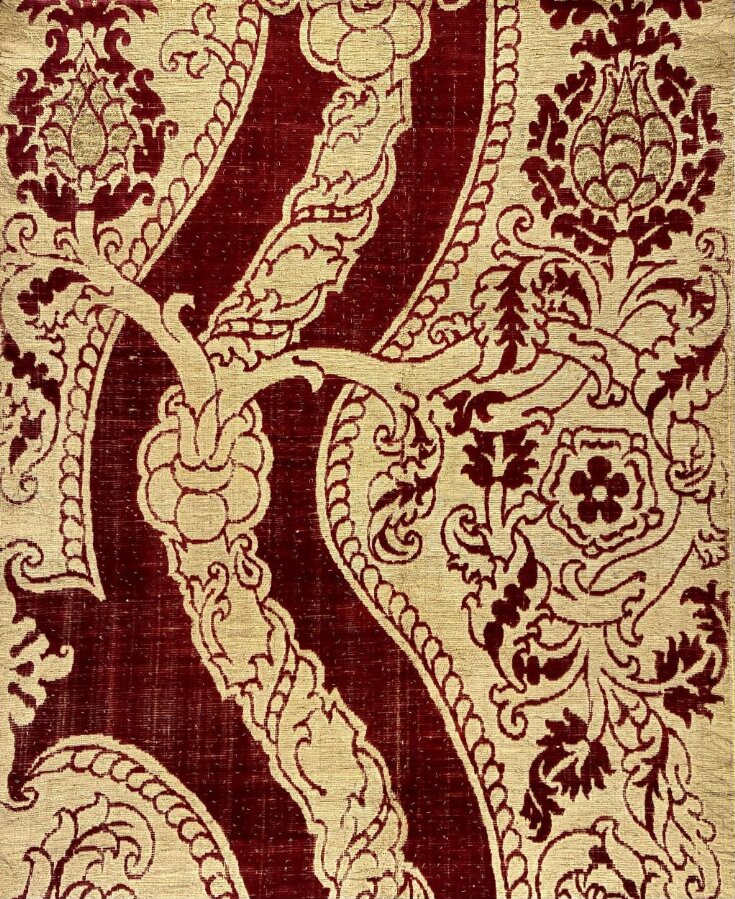

This velvet is particularly rich and would have been complex to weave because of both its raw materials and its construction. It is most likely to have been made in Italy at the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century when Italy and Spain were the main silk-weaving centres in Europe, and the pomegranate incorporated into its design was a popular motif. Both Florence and Venice had skilled craftsmen who made these textiles for domestic and international markets, having served a long apprenticeship in order to acquire the requisite skills.

The scale of the pattern repeat meant that the textile was seen to its greatest advantage in wall hangings, although paintings from the period show that such patterns were also used for dress, both secular and ecclesiastical. Indeed, even after it fell from fashion it went on being used in the vestments worn by Catholic priests.

The scale of the pattern repeat meant that the textile was seen to its greatest advantage in wall hangings, although paintings from the period show that such patterns were also used for dress, both secular and ecclesiastical. Indeed, even after it fell from fashion it went on being used in the vestments worn by Catholic priests.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Velvet cloth-of-gold, with loops of silver-gilt thread |

| Brief description | velvet with cloth of gold ground, 1475-1500, Florentine; crimson, pomegranates, a griccia pattern, boucléand allucciolato effects |

| Physical description | Crimson velvet cloth-of-gold, with weft loops of silver-gilt thread, woven with undulating stems bearing stylized pomegranates. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | From the Bardini Collection (see below). Acquired on 28 April 1892 with a range of other Renaissance objects. At the same time, objects were sent to Edinburgh and Dublin. MA/1/B8359. Historical significance: The word 'tissue' was fist used to denote textiles with metal loops during the 15th century, in connection with velvets woven with bouclé metal wefts, and as these metal loops came to be incorporated into lampas and brocatelle silks, during the 16th century 'cloth of tissue' came also to be applies to these cloths. The various 'tissues' were expensive cloths destined for the luxury market. During the first half of the 15th century silk velvets began to be woven with looped effects, both the loops scattered through the pile and with massed gold loops on areas voided of pile (L. Monnas 1998:63). |

| Historical context | Place of production European velvet production in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was mainly located in the Italian states (Lucca, Venice, Florence, Genoa, etc) and in cities in the Spanish peninsula which had been occupied by the Moors for seven hundred years before 1492 (Valencia, Granada, etc.) Guilds regulated production, organizing training and workshop practice. Velvet-making was highly skilled and craftsmen could only operate independently once they had trained for about ten years and paid their guild dues. Both raw materials (silk and gold) and labour were costly, velvet being one of the techniques in silk manufacture that required specialised - highly valued and remunerated - skills. Status and use This costly fabric is typical of the fine silk textiles imported into England from Italy under licences stipulating that the monarch should have 'first sight and choice' of them. Under Henry VIII the use of gold-looped fabrics, termed 'cloth of gold of tissue', was restricted by law to the king and his immediate relatives (with notable exemptions). It cost £2-£11 per yard, at a time when some royal craftsmen earned 12d (5p) per day. 'Tissues' with this particular design of sinuous, branching pomegranates were popular for noble dress and furnishings from the 1470s into the early sixteenth century, but by the 1540s their popularity as dress fabric had waned, superseded by a newer range of designs. Thereafter, they continued to be used for secular and ecclesiastical furnishings and for ecclesiastical vestments - too valuable to discard these cloth-of-gold were mainly relegated to the chapel. The scale of their designs was particularly suited to furnishings rather than dress. Although this panel is impressive, it does not represent the very finest quality; the Fayrey pall incorporates a finer cloth-of-gold and the textile of the Henry VII cope is richer still. Similar velvets Stonyhurst cope (red) on display in the British Galleries, V&A. Chasuble (green), Bennefantenmuseum-Limburgs Museum voor Kunst en Oudheden, Maastricht; 433BM (cat. 46, Christa C. Mayer Thurman, Raiment for the Lord's Service. A Thousand Years of Western Vestments, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1975, pp. 132-3) Dalmatic (red) with late 15th-early 16th century Flemish orphrey bands, Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire, Brussels (cat. 48 in Mayer Thurman, Raiment for the Lord's Service, p. 138 with illustration) Length of silk (red), Musée des Tissus in Lyon (illustrated in Orsi Landini, Roberta, 'The Triumph of Velvet. Italian production of velvet in the Renaissance', in de' Marinis, Fabrizio, ed. Velvet. History, Techniques, Fashions. Milan: Idea Books. 1994, p. 22 (this is a very useful overview of velvet production). Described as a silk cut voided velvet with gold brocading and bouclé wefts. Florence, third quarter of fifteenth century. Chasuble, Schnutgen Museum in Cologne (Inv. - Nr P218); a date of the last quarter of the fifteenth century is suggested for the velvet and 1509 for the embroidery. The shape of the chasuble may date to the seventeenth century. Sporbeck, Gudrun. Die Liturgischen Fewander. 11. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Cologne: Museum Schnutgen, 2001, Cat. 52, pp. 209-11. Cope of Saint Antoli, Catalonia (Morral i Romeu, E. & Segura i Mas, A. La Seda a Espanya, Tarasa: CDMT, 1991, p.71 - black or dark blue rather than red. Length of similar velvet, Badia Fiorentina, Florence Tessuti Serici Italiani 1450-1530, Electa, Milan, 1982, cat. no. 8, p. 84 and illus. p. 85 and others) Representations of similar velvets Dossal to throne and cloth of gown of St Catherine in Hans Memling, The Mystical Marriage of St Catherine, 1479. Hans Memlingmuseum, Bruges Dalmatic in Adam Elsheimer, Stoning of St Stephen, circa 1602-5. National Gallery of Scotland. Chasuble in Clemente Torres (1662-1730), St Nicolas of Bari, Museum of Fine Arts, Seville. Cope in Francisco de Zurbaran, St Ambrose for the Monastery of San Pablo el Real, Seville, 1626. Museum of Fine Arts, Seville. Collecting history Stefano Bardini (1836-1922), the most famous Italian dealer of his day, sold to collectors in America, Berlin, London, Florence, Paris and Vienna. He was a dealer from 1874, and had a gallery in Florence from 1881; a bequest in his will created the Bardini Museum. His first contact with South Kensington Museum was in 1884; he subsequently corresponded with the Museum for thirty years, and was one of the dealers who played the largest part in the history of the Museum before 1900. He sold objects; and even held a sale in London at the New Gallery in November 1898. The majority of pieces bought from him by the Museum were genuine and of high quality. (Clive Wainwright, 'The Making of the South Kensington Museum IV', Journal of the History of Collecting, Vol. 14, no. 1, 2002, pp. 72-77). |

| Summary | This velvet is particularly rich and would have been complex to weave because of both its raw materials and its construction. It is most likely to have been made in Italy at the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century when Italy and Spain were the main silk-weaving centres in Europe, and the pomegranate incorporated into its design was a popular motif. Both Florence and Venice had skilled craftsmen who made these textiles for domestic and international markets, having served a long apprenticeship in order to acquire the requisite skills. The scale of the pattern repeat meant that the textile was seen to its greatest advantage in wall hangings, although paintings from the period show that such patterns were also used for dress, both secular and ecclesiastical. Indeed, even after it fell from fashion it went on being used in the vestments worn by Catholic priests. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 81-1892 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | May 17, 2018 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest