Hampi (Vijayanagar) Bellary District: 'Lotus Mahal'.

Photograph

1856 (photographed), 1910 (printed)

1856 (photographed), 1910 (printed)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

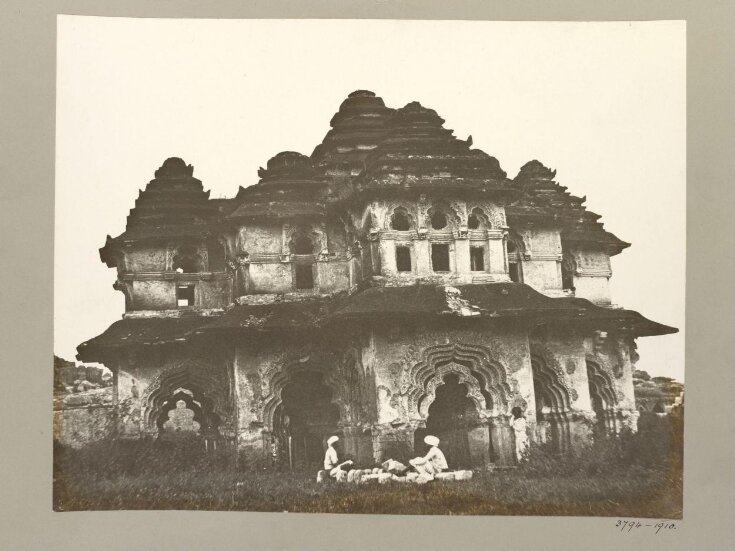

This photograph shows the 'Lotus Mahal', Hampi (Vijayanagara).

Vijayanagara, meaning ‘city of victory’ was the imperial capital of the last great Hindu empire to rule south India. Established in 1336 and named after its capital, the Vijayanagara empire expanded and prospered throughout the next century. In 1565, this impressive city was sacked by armies from the Deccan sultanates and never rebuilt. Now known as the ‘Group of Monuments at Hampi’, the site represents the empire’s finest and highest concentration of architecture. Classified into religious, courtly and military buildings, its pillared audience halls and towering gateways are its stylistic hallmarks. Many secular buildings bear Islamic features, displaying the city’s cosmopolitan inception. Some of its religious complexes remain in use today.

Amateur British colonial photographer, Alexander Greenlaw was the first to extensively photograph the site in 1855-56. The resulting series of waxed paper negatives were made available to the V&A and printed in 1910. These are the earliest known prints.

Vijayanagara, meaning ‘city of victory’ was the imperial capital of the last great Hindu empire to rule south India. Established in 1336 and named after its capital, the Vijayanagara empire expanded and prospered throughout the next century. In 1565, this impressive city was sacked by armies from the Deccan sultanates and never rebuilt. Now known as the ‘Group of Monuments at Hampi’, the site represents the empire’s finest and highest concentration of architecture. Classified into religious, courtly and military buildings, its pillared audience halls and towering gateways are its stylistic hallmarks. Many secular buildings bear Islamic features, displaying the city’s cosmopolitan inception. Some of its religious complexes remain in use today.

Amateur British colonial photographer, Alexander Greenlaw was the first to extensively photograph the site in 1855-56. The resulting series of waxed paper negatives were made available to the V&A and printed in 1910. These are the earliest known prints.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Hampi (Vijayanagar) Bellary District: 'Lotus Mahal'. (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Silver gelatin print from waxed paper (calotype) negative |

| Brief description | Photograph of Hampi (Vijayanagara), India, by Colonel Alexander Greenlaw taken in 1856, gelatin silver print, London, 1910 |

| Physical description | This photograph shows a slightly oblique view of a two storeyed stone structure with symmetrical protruding porches to each side producing a stepped layout. Each section has its own tiered dome. The lower storey has receding, multi-lobed arches with plaster decorations and bracketed floating arch sections. It is mounted by a heavy eave. The upper storey has triple arched windows in the front central bay and single arched window openings on the side projections, all of which have receding multi-lobed detail. The structure is somewhat dilapidated and overgrown with some damage to the plasterwork and eaves and it appears that the whole structure may have subsided some time earlier. Three figures are posed to the front of the building, presumably to indicate scale. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | The V&A holds 61 prints of Vijayanagar and 5 miscellaneous prints (Anglo-Indian architecture in Bellary and Indian tree studies) by Greenlaw. These prints were specially made in 1910 for the V&A collection from the original 1856 negatives which were lent to the museum by Mrs Armitage of East Sheen. Of these 66 prints, 45 are currently held in the Asian Dept and 21 in the Word and Image Dept. The negatives along with another set of prints, also made in 1910, were 'rediscovered' in a private collection in 1980. In 1983, the collector, Edgar Gibbons, a retired Army officer from Cornwall, having recently purchased the negatives and prints from a relative of Greenlaw, made the negatives available to the Vijayanagara Research Project photographer, John Gollings. Gollings made two new sets of prints, one of which he sent to the collector and one of which he kept. The collector's original negatives and 1910 prints were subsequently purchased by the Alkazi Foundation. The Alkazi Foundation currently holds a duplicate set with the exception that the Alkazi does not hold No’s 3795-1910 (Alkazi holds the negative for this image) and 3784-1910. Gollings donated his 1983 set to the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) along with a series of his own photographs. Fascinated by Greenlaw’s images, Gollings painstakingly rephotographed, in 1983, sixty of the exact sites visited by Greenlaw. This was to enable the Vijayanagara Research Project to measure the change in the condition of the monuments over time. Through this process of comparative photography, Gollings assumed that a number of the Greenlaw negatives had been cut down at some stage from their original 16”x18” large format to fit a smaller printing frame. However the negatives do not appear to be cut. Alternatively it is possible that Greenlaw either had two cameras or was able to produce different sized negatives from the one camera. Mount inscriptions - The photograph is top mounted on grey board and shows the original 1910 typed, and handwritten where noted, inscriptions: Top left corner: 'ARCHITECTURE, India' Top centre: 'IIbd' and below, a V&A Library embossed stamp Top right corner: 'C' Bottom left corner: 'HAMPI (Vijayanagar) Bellary District: / [Handwritten:] Pavilion of the Palace.' Bottom right corner: [handwritten] '3794-1910' and below, an attached typed label 'From a paper negative made by Colonel A.J. Greenlaw of the Madras Staff Corps in 1855-56' Verso: [handwritten] 'Hampi (Vij)/ Pavilion of the Palace' Historical significance: Architectural significance (the architecture as subject) - This photograph shows a view from the west of the two storeyed pavilion located in the Royal Centre popularly known as the 'Lotus Mahal'. This celebrated monument which dominates the zanana enclosure probably served as a council chamber. The pavilion is laid out on a square mandala-like plan with symmetrical projections on each side. The basement and nine pyramidal towers derive from temple architecture. The lobed arches and surrounding plaster decoration and the interior domes and vaults are Islamic in style. This building displays the Vijayanagara secular, or courtly, style at its best. Concentrated around the Royal Centre, secular architecture at Vijayanagara can be distinguished by an overall Islamic appearance. There are no inscriptions or epigraphs linked to any of these structures and therefore remain only tentatively identified and dated. However, it should be noted that these buildings are closely associated with other secular and religious buildings within the royal centre used by the Hindu rulers, court and military and should not be attributed to any direct Muslim patronage, unlike structures such as tombs in the various Muslim quarters of the city. Rather, these structures represent something new and characteristic of Vijayanagara. The Hindu court, the military, and the architects and craftsmen of Vijayanagara were well aware of the Deccan Islamic architectural traditions. By the mid-fifteenth century, buildings at the capital began to imitate the Islamic style as a result of a consciously cultivated taste for Islamic forms in which a new artistic tradition evolved that was neither purely Islamic nor Hindu. As such, Islamic-derived elements were synthesized with Hindu-derived elements, forming new compositions such as the ‘Lotus Mahal’ and elephant stables. Islamic features such as plaster decoration with geometric and arabesque motifs were Hinduized with lively animals and birds and in turn, Hindu forms such as moulded basements and temple-like parapets and sculptures were Islamicized by reducing the depth of carving to produce flat relief. (Identification: Gordon, File 99.02.0003 and similar to Nagaraja Rao, Pl.42) For similar architecture within the series, see 3792-1910 and 3791-1910. The Vijayanagara empire ruled southern India from 1336 -1565. As India’s last large state system prior to the British colonial takeover, it has been perceived as the final great era of 'traditional' Hindu India and also as a transitional phase which transformed Indian society from its medieval past towards its modern, colonial era. The empire built its imperial capital, Vijayanagara ('city of victory'), around the ancient religious centre of the Virupaksha temple on the south bank of the Tungabhadra River at Hampi, Bellary District, Northern Karnataka. Three dynasties ruled from Vijayanagara: the Sangama (1336-1485), the Saluva (1485-1505) and the Tuluva (1505-1565). By the year 1500,Vijayanagara was the second most populous city (after Beijing) in the late medieval world. The Vijayanagara rulers fostered developments in intellectual pursuits and the arts, warfare, engineeering and agriculture, and were also great patrons of religion. The ruins at Hampi represent the largest concentration of Vijayanagara architecture and are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, known as 'the Group of Monuments at Hampi'. Vijayanagara architecture consists of religious, courtly and civic buildings and sculpture and is characterised by a return to a more serene art of the past, taking elements from the Chalukya, Hoysala, Pandya and Chola periods. Granite, the local and durable stone, was used with plaster applied to many sculptures to produce a smooth finish which was then gilded or colourfully painted. Photographic significance (the photography as subject) – This photograph is significant as one of the earliest known photographic records of this celebrated building before restoration work was carried out, revealing the basement The delicate stone frames supported on brackets in the arches have all disappeared. Greenlaw also photographed this structure from further to the left so as to include the octagonal watchtower in the right of the picture. Greenlaw's systematic coverage of the ruins of Vijayanagara at Hampi is significant within the connected histories of colonialism and photography. Taken in 1855-56 when the use of photography in India was gathering momentum as the new tool of documentation, Greenlaw’s series is important as the earliest extensive photography in India of an archaeological site. While Greenlaw exhibited prints as early as 1856, none are now known to exist from the time the negatives were made, therefore the V&A’s 1910 prints represent the earliest extant photographs. As architectural photography, the series successfully determines the condition of the monuments at that time. Since then, many of the structures, in particular their superstructures and sculpture, have altered in appearance due to further disintegration, banditry, conservation, tourism and development, and some have disappeared altogether. Thorough and perceptive as one of the early amateur photographers who introduced the medium in India, Greenlaw was influenced by the picturesque aesthetic style of his era yet his compositions show a lack of artifice and a clarity of viewpoint. John Gollings writes: “ He has established many of the basic descriptive views and given a coherence to the city which is every architectural photographer’s aim. His work is seminal in conception and outstanding in its execution” (Rao 1988, p.18). Greenlaw worked with large format 16" x 18" negatives which gave good detail to architectural subjects, yet while not unusual for work of this period, they were cumbersome. Despite this and the harsh Indian climate, Greenlaw became technically adept at using the negative-positive calotype process for which paper was impregnated with light sensitive chemicals and then waxed to make the negative translucent for subsequent printing by contact rather than enlargement. The waxed paper process was largely replaced by glass plates in the late 1850s however Greenlaw continued to use it because it suited his particular working conditions and allowed him to process back at base thus enabling a faster coverage of the site. His cumbersome camera, lens and equipment would have required an ox cart and porters for mobility. Long exposures meant few people were caught as subjects unless posed so it is likely that the figures in many of Greenlaw's photographs were his porters, posed to indicate scale and a sense of place. 19th century paper negatives were only sensitive to blue light making them better suited than modern film to photographing granite and brick against blue sky typically found at Vijayanagara. However, Greenlaw's photographs display some tonal difficulties. The high contrast film necessitated low contrast development with resultant tonal merge problems. Greenlaw somewhat crudely countered this by blocking out areas of sky on the negatives with Indian ink. |

| Historical context | No photographic prints are known before 1910. A ca. 1886 woodcut illustration (artist unknown) taken from No. 3760-1910 appears in the album, Taylor and Fergusson, 'Architecture in Dharwar and Mysore', London: John Murray, 1866, p.45, in Fergusson, 'History of Indian and Eastern Architecture', Vol. I, London: John Murray, 1910, Fig.168, and later in Fritz, Michell and Nagaraja Rao, 'The Royal Centre at Vijayanagara: Preliminary Report' Melbourne: Department of Architecture and Building, University of Melbourne, Vijayanagara Research Centre, Monograph Series No. 4, 1984, p.4, suggesting that some Greenlaw images formed a part of James Fergusson’s large collection of photographs of Indian architecture. While Fergusson published photographs of Vijayanagara by Pigou and Neill, it is possible that the greyness of Greenlaw’s tonal range restricted the appeal of his photographs for publication. However, their fine picturesque compositions made them suitable as a basis for illustrations. Contemporary to Greenlaw, photographers Dr William Harry Pigou and Dr Andrew Charles Brisbane Neill were also active in Vijayanagara in the mid 1850s working with paper negatives. Also Captain Edmund David Lyon from the 1860s. |

| Subject depicted | |

| Place depicted | |

| Summary | This photograph shows the 'Lotus Mahal', Hampi (Vijayanagara). Vijayanagara, meaning ‘city of victory’ was the imperial capital of the last great Hindu empire to rule south India. Established in 1336 and named after its capital, the Vijayanagara empire expanded and prospered throughout the next century. In 1565, this impressive city was sacked by armies from the Deccan sultanates and never rebuilt. Now known as the ‘Group of Monuments at Hampi’, the site represents the empire’s finest and highest concentration of architecture. Classified into religious, courtly and military buildings, its pillared audience halls and towering gateways are its stylistic hallmarks. Many secular buildings bear Islamic features, displaying the city’s cosmopolitan inception. Some of its religious complexes remain in use today. Amateur British colonial photographer, Alexander Greenlaw was the first to extensively photograph the site in 1855-56. The resulting series of waxed paper negatives were made available to the V&A and printed in 1910. These are the earliest known prints. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 3794-1910 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 14, 2007 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest