| Bibliographic references | - Engen, Rodney. The Age of Enchantment. Beardsley, Dulac and their Contemporaries 1890-1930, London : Scala Publishers Ltd., 2007

no.18

- Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley : a catalogue raisonne. New Haven : Yale University Press, [2016] 2 volumes (xxxi, [1], 519, [1] pages; xi, [1], 547, [1] pages) : illustrations (some color) ; 31 cm. ISBN: 9780300111279

The entry is as follows:

1050

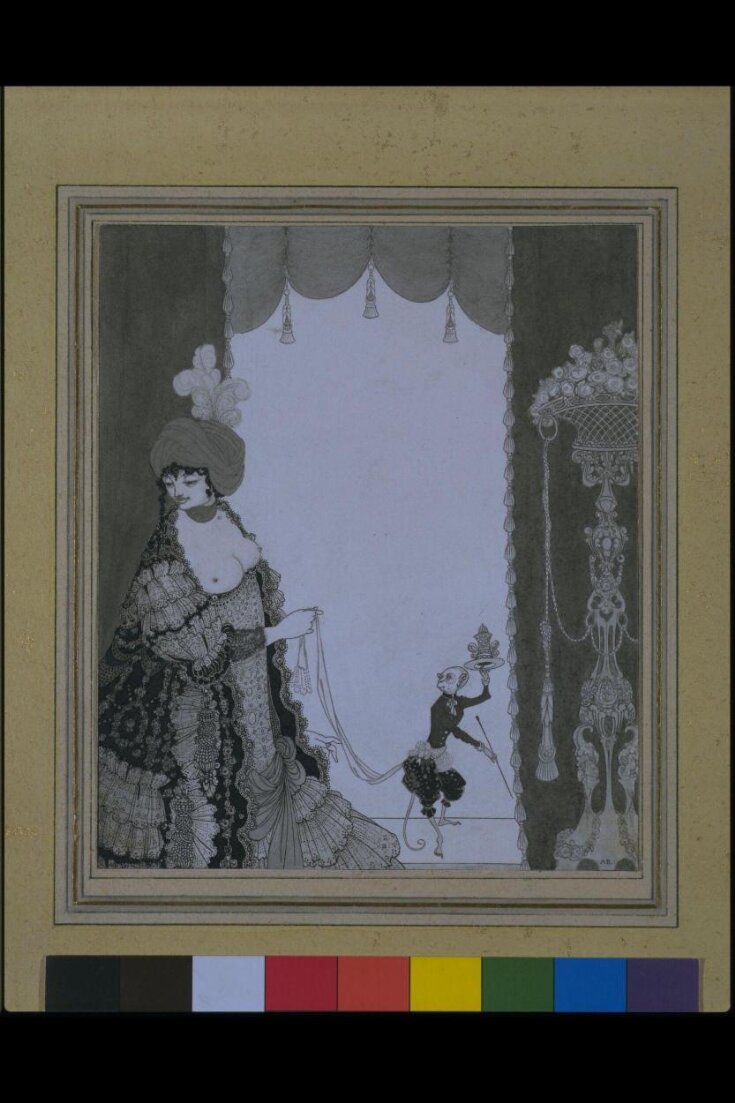

The Lady with the Monkey

By 22 October 1897

Pen, brush, Indian ink and wash over pencil on white wove paper laid down on brown card speckled with gold and held to stiff backing with corner mounts; 7 13/16 x 6 5/8 inches (200 x 690 [sic, should be 169] mm); signed.

INSCRIPTIONS: Recto inscribed in ink by artist [monogram on base of epergne]: A.B.

FLOWERS: Rose [Bourbon type] (love, passion).

PROVENANCE: Given by the artist to his sister Mabel, Mrs Geprge Bealby Wright; bequeathed to Ellen Beardsley; bt. Sir Edmund David; ... ; Sir Gerald F. Kelly (by 1923); Sotheby’s (London) sale 14 December 1955 (73); bt. Mrs Frolich; bt. Arcade Gallery in 1955; bt. R. A. Harari, by descent to Michael Harari; bt. Victoria and Albert Museum in 1972 with the aid of a contribution from the National Art Collections Fund.

EXHIBITION: London 1908a (216, where titled ‘Mademoiselle de Maupin’), 1913 (159); London 1923-4 (48); Johannesburg ?1955 (220); London 1966-8 (574); 1973b (53); Munich 1984 (262); Rome 1985 (14.4); London 1993 (118); Tokyo 1998-9 (181).

LITERATURE: Vallance 1909 (164. vi); National Gallery, London 1923-4 (no. 48 or no. 53); Gallatin 1945 (no. 1089); Reade 1967 (p. 364, n. 492); ‘Letters’ 1970 (pp. 380-1, 399, 408, 411, 413, 418); Sitwell 1973 (p. 262); Hodnett 1982 (p.257); Wilson 1983 (plate 44); D. March 1985 (pp. 11, 15-18); Fletcher 1987 (pp. 178-9); Reade 1989b (pp. 34-5); Zatlin 1990 (pp. 157, 183, 188, n.28); Samuels Lasner 1995 (no. 121); Zatlin 1997 (pp. 128-31, 255, 257); Wilson in Wilson and Zatlin 1998 (p. 248, nos. 161-6, Section 12).

REPRODUCED: In photogravure as plate 6 in the series ‘Six Drawings Illustrating Theophile Gautier’s Romance Mademoiselle de Maupin by Aubrey Beardsley’, published by Leonard Smithers, London, December 1898; ‘Later Work’ 1901 (no. 165); Reade 1967 (plate 492); Clark 1979 (plate 60); Wilson 1983 (plate 44); D. March 1985 (no. 4, p.13; no. 8, p. 20).

Beardsley first mentioned this drawing on 22 October 1897 when he sent it to Leonard Smithers, saying, another picture. A very good one I think… There is pencil work on the lady’s face and a little on the hand, so threaten Swan with eternal punishment if they touch the drawing (‘Letters’ 1970, p. 380). There is no further mention of it until 17 December, when he wrote to Smithers requesting the return of the drawing and his intent to use it for ‘Volpone’: ‘Please send me by return the drawing you have of mine of a Lady and a monkey at a window, I shall certainly press it into the service of ‘Volpone’ as an initial for the Rhymed argument’ (p. 408). Less than a week later, on 22 December, he informed Smithers that he would pencil in the initial on this drawing and ‘on return of drawing and block being made you can take out the letter or leave it as you please’ (p.411). Four days later he decided that this design would not work for ‘Volpone’: ‘If you have not already sent me lady and the monkey do not do so as it will be quite out of keeping with the rest of the initials’ (p. 413). Despite his indecision about the proper place for this drawing, Beardsley’s hand was certain when he made it. The ‘delicacy of the brushwork is astounding for an artist who had only recently begun to use this medium and one, moreover, who was practically dying’ (National Gallery, London, 1923-4, no. 48). It is in a new style that evolved from ‘A Nocturne of Chopin’ and ‘Chopin’s Third Ballade’ (nos. 920, 931 above), a technique ‘vaguely reminiscent of aquatints’ that did not have strong influence on succeeding artists (Reade 1989b, pp. 34-5). His use of blank space was influenced by Japanese woodblock prints (Zatlin 1997, pp. 128-31), yet that space takes on a positive form of its own before the Lady moves into it and inscribes it with her actions.

As Beardsley grew more and more ill and felt more and more isolated, he relied on books and his memories of places he had seen for decorative details in drawings. The window treatment in this design, the bookplate for Olive Custance and ‘Arbuscula’ (nos. 1077 and 1075 below), for example, recalls the windows of the banqueting room gallery and the music room gallery at Brighton Pavilion. In addition, here, Beardsley imagines a woman from the 1830s based on Gavarni’s fashion plates for ‘La Mode’ and, in the words of Sacheverell Sitwell, makes an ‘Imaginary version of 1830s sinister fragility and charm’ (1973, p. 262). Similarly, the miniature monkey, a later version of Beardsley’s fetus figure, recalls male surrogates in the work of Hogarth and other artists of the eighteenth century, and it ‘splendidly mimes the mannered ennui of D’Albert’ (Reade 1967, p. 364, n. 492; Zatlin 1990, pp. 157, 183, 188; Fletcher 1987, pp. 178-9). Or perhaps, this monkey on a window ledge that ‘act[s] as Maupin’s master of ceremonies is of Beardsley’s own invention’ (Wilson 1983, plate 44). Beardsley’s image can be linked with Paul Verlaine’s poem ‘Cortege’, published in ‘Fetes Galantes’ (1869), in which a lady is accompanied by a monkey wearing a brocade jacket, which is fascinated by her decolletage; Beardsley dresses his animal also in embroidered trousers (Munich 1984, no. 262; D. March 1985, p. 11; Zatlin 1990, p. 188, n.28). Kampmann has proposed a link to Flaubert’s ‘Temptation of St Anthony’ (1874) in which the Queen of Saba appears in a dress with a long train, the end of which is carried by a monkey (Editions Garnier 1954, p. 42; unpublished letter to David March 25 April 1986, in possession of Simon Wilson, London).

This is the most powerful, complex and enigmatic of Beardsley’s illustrations for this novel (Wilson in Wilson and Zatlin 1998, p. 248, no166 Section 12). And assuredly some proof lies in critics’ disagreements about who the lady is. March speculates that the woman could be D’Albert himself, perhaps because Beardsley takes D’Albert’s worship of female beauty and his androgyny to the extreme by imagining him as a full-breasted woman (1985, pp. 15-18). Her features are almost identical to those of the woman in ‘The Lady at the Dressing Table’ (no. 1048 above), who shares facial features, specifically the nose and lips, with D’Albert. Or she could be Mademoiselle de Maupin, dressed for the first time as a woman, when she plays Rosalind in Shakespeare’s ‘As You Like It’, standing in the doorway of the room in which Rosette and D’Albert await her. If so, it does not precisely follow Gautier’s description except in her great beauty and her bare bosom through which she becomes ‘one of the great examples in art of imagined female beauty and remarkable particularly for its delicate but powerful sensuality’ (Wilson 1983, plate 44; see also Wilson in Wilson and Zatlin 1998, nos. 161-6). Or the monkey ‘leads the bare-breasted lady across the threshold into a room that perhaps contains sexual knowledge’, and it functions as one of Beardsley’s integrated observers ‘mimicking the way some late-Victorian men looked or pictures or at life’ (Zatlin 1997, pp. 255, 257).

|