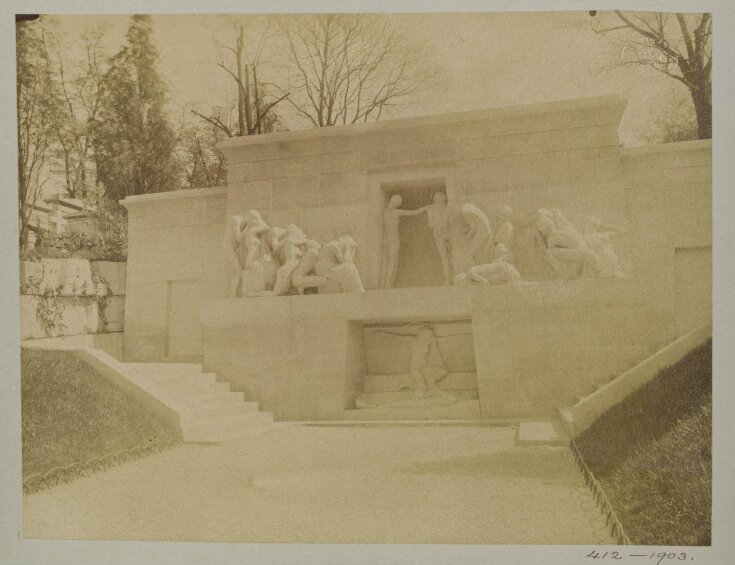

Bartholomé monument 'Aux Morts in the cemetery Père Lachaise, Paris

Photograph

c. 1900 (photographed)

c. 1900 (photographed)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Eugène Atget (1857-1927) took up photography as a professional in the late 1880s. Details of his earlier life are shadowy. He is known to have been a sailor and then an amateur actor, which may account for the ‘stage set’ quality of many of his images. He seems to have lived a largely secluded life in his apartment in Paris.

His project to record ‘Old Paris’ began around 1897 and continued until the 1920s. In it, Atget was driven by the disappearance of buildings as schemes of modernisation swept the city. Ignoring the grand new vistas, he set out to record the character and details of the timeworn streets. He made a stock of prints for sale to artists, museums and libraries, in France and abroad, selling some 600 prints directly to the V&A.

Today, however, Atget is admired less as a record photographer and more as a forerunner of Surrealism and of modern approaches to the art of photography. His urban scenes - featuring snatched glimpses, tangential perspectives, odd reflections and bizarre details - convey a distinctly modern experience of the city. In 1936, critic Walter Benjamin described how these images operated beyond their ostensible purpose, appearing unintentionally, but uncannily, like the ‘scene of a crime’.

This shift in perception about Atget’s work began in the last years of his life, when he met Berenice Abbott, a young American working in Paris for the photographer Man Ray. After his death, Abbott bought the remains of his archive and began to promote his work. She was entranced by the strangeness of Atget’s photographs, seeing in them a Surrealist vein as well as a ‘relentless fidelity to fact’ and a ‘deep love of the subject for its own sake’.

His project to record ‘Old Paris’ began around 1897 and continued until the 1920s. In it, Atget was driven by the disappearance of buildings as schemes of modernisation swept the city. Ignoring the grand new vistas, he set out to record the character and details of the timeworn streets. He made a stock of prints for sale to artists, museums and libraries, in France and abroad, selling some 600 prints directly to the V&A.

Today, however, Atget is admired less as a record photographer and more as a forerunner of Surrealism and of modern approaches to the art of photography. His urban scenes - featuring snatched glimpses, tangential perspectives, odd reflections and bizarre details - convey a distinctly modern experience of the city. In 1936, critic Walter Benjamin described how these images operated beyond their ostensible purpose, appearing unintentionally, but uncannily, like the ‘scene of a crime’.

This shift in perception about Atget’s work began in the last years of his life, when he met Berenice Abbott, a young American working in Paris for the photographer Man Ray. After his death, Abbott bought the remains of his archive and began to promote his work. She was entranced by the strangeness of Atget’s photographs, seeing in them a Surrealist vein as well as a ‘relentless fidelity to fact’ and a ‘deep love of the subject for its own sake’.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Bartholomé monument 'Aux Morts in the cemetery Père Lachaise, Paris (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Albumen print from gelatin dry plate negative |

| Brief description | Albumen photograph by Eugène Atget, late 19th century or early 20th century. Photograph of the monument 'Aux Morts' by Bartholomé in the cemetery Père Lachaise, Paris, France |

| Physical description | An albumen print mounted on green card from a series of photographs by Eugène Atget that set out to record 'Old Paris and its Environs'. |

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | (This photograph is part of a set of images acquired directly from Atget between 1903 and 1905. All of these images bear the National Art Library blind stamp on the print itself. The name of the object, its location and the museum number are written by hand in ink on the mount. Occasionally, there is an additional label attached to the mount with further annotations.) |

| Credit line | Purchased from the artist, 1903 |

| Object history | In 1926, the photographer Eugène Atget (1857-1927) was approached by Man Ray and his Surrealist colleagues, seeking Atget's approval to use an Atget photograph from 1912 for the cover of their magazine, La Révolution Surréaliste. The 69-year-old Atget was not part of the Surrealist 'clique', rather, he was known as a photographer of objects and places - at one time a sign outside his studio announced: 'Documents for Artists'.(1) He came to the Surrealists attention by sheer coincidence, as he lived in the same Parisian street as Man Ray. The image the Surrealists chose, descriptively titled by Atget L'Eclipse - Avril 1912, appeared on the magazine's cover with the more allegorical caption: Les Dernières Conversions [The Last Conversions]. Atget refused to allow his name to be used with the image. According to Man Ray, Atget supported his refusal with the inscrutable explanation: 'These are simply documents I make'.(2) Despite a career that spanned over 30 years and an archive of over 8,500 negatives, the details of Atget's life that have revealed themselves to historians have failed to provide a more nuanced analysis of Atget the man than this oblique statement. Faced with such an unyielding subject, and an uneasiness with the merely documentary or merely picturesque, it is not surprising that Atget scholars have constructed a variety of views of the reclusive photographer. He is variously portrayed as an unconscious Surrealist, a pioneer of the straight approach, a naïve genius like 'Douanier' Rousseau, and a master topographer. Eugène Atget was born on 12 February 1857, an only child to Jean-Eugène and Clara Atget in Libourne, an inland port on the Dordogne River in the Gironde region of France. His father, a travelling salesman, died while in Paris on business. This was shortly followed by the death of Atget's mother, leaving their son an orphan at the age of five. He was placed in the care of his maternal grandparents Victoire and Auguste Hourlier, a clerk at the nearby freight station. Libourne was populated by steamers and ships returning from, or on their way to, the Far East, Africa, and South America, and Atget would have been exposed to the world beyond the small port. After finishing his studies, Atget, as did many of the local youth, signed up as a cabin boy on a ship (though the ports that Atget visited during this period in his life remain a mystery). In 1878 Atget moved permanently to Paris pursuing admission into the prestigious and highly competitive National Conservatory of Music and Drama. Without formal training, and a stature of only 5' 5" (in addition to a face whose features have been described as 'discordant'), Atget was turned down.(3) This coincided with his immediate drafting into the army for five years of active duty. Despite his soldiering obligations, Atget was determined to pursue theatrical studies, and after one year of full-time military service, he reapplied to the Conservatory, passed the exams, and enrolled in the autumn of 1879. At first, Atget appeared to successfully juggle his military commitments with his theatrical lessons. He studied under the celebrated actor Edmond Got (1822-1901), who saw something in the 'kid from Bordeaux', predicting that he would 'amount to something, I hope'.(4) But by the end of the year, Got's enthusiasm for the over-committed student waned, citing his 'inelegant accent.'(5) Atget was not asked to return for the following year. Without the Conservatory degree, Atget was denied access to legitimate French theatres and spent the next decade pursuing minor roles with a provincial troupe. These years spent in Paris and touring the countryside have been credited with instilling in Atget a sympathy towards the landscape and traditions of provincial France, a sympathy which one can argue finds visual representation in the subjects he photographed. His circle of friends included actors and many of the artists studying at the École des Beaux-Arts, near his apartment in Paris. It was also during this period that Atget met the actress Valentine Delafosse Compagnon, his life-long companion. The details of when or why Atget took up photography are unknown. Financial need was certainly an impetus. He had taken up painting shortly after leaving the stage (a sideline he pursued even once his photographic practice was established), but his lack of formal training would have put him at a professional disadvantage to the established artists within his social community. By the mid-1880s, advances in the manufacture of the dry plate negative made competence in the technical aspects of photography easier to master and the technique became widely disseminated. Unlike the wet collodion negative which preceded it, the dry plate was commercially manufactured, ready for use. This made it well-suited for outdoor work, making it easier for the photographer to leave the studio. With the popular uptake of the medium, specialized publishing houses were established, fulfilling the needs of artists, publishers, and illustrators who would use photographs as resources for their work. It was within this specialised niche that Atget set himself up as a professional photographer. As part of the artistic community, he was aware of artists' needs and was well-placed to provide documents for their work. Furthermore, the diminutive size of his venture would reduce the risk of multiple artists working from the same photographs of models and other images. In 1892, a small notice appeared in the French-Belgium arts journal La Revue des beaux-arts: 'We recommend to our readers M. Atget, photographer, 5 Rue de la Pitie (Paris), who offers artists landscapes, animals, flowers, monuments, documents, foregrounds for painters, reproduction of paintings. Will travel. Collections not in public circulation'.(6) Atget's photographic equipment was the standard for the day, including a large wooden camera equipped with bellows, a wooden tripod and standard-size gelatin glass negatives (18 x 24 cm), from which he would produce albumen prints with an untrimmed size roughly the same as the negatives. It was a heavy load that Atget carried across Paris. However, he remained committed to this equipment throughout his career, even as advances made such cumbersome equipment less desirable. In about 1897, Atget expanded his business and turned his camera towards a subject that would prove to be inexhaustible: Paris. Producing some 1,400 images over a period of four years, Atget's new focus meant his output was now more self-defined. By 1901, he was known as a specialist photographer of the subject of Paris, and more specifically, old Paris and its environs. His catalogue included traditional street trades, picturesque street views, and the art, monuments and architecture of old Paris. This development in Atget's career ran parallel to civic planner Baron Haussmann's scheme to modernize Paris and the concurrent public outcry that resulted as the old buildings were being destroyed. While Atget's focus on this subject may have been genuinely motivated by a passion for the history and traditions of the historic neighbourhoods, public interest in preservation served to make Atget's enterprise commercially viable. It is probably not a coincidence that Atget initiated his study of old Paris within a few months of the founding of the official preservation commission. At this time, Atget printed a new business card: 'E. Atget, "Creator and Purveyor of a Collection of Photographic Views of Old Paris"'.(7) Atget's shift in subject matter expanded his client base to include museums, archives and libraries, though he never abandoned his work for artists. By 1910, Atget's reputation among a wide range of institutions was well established. In a reminiscence by one of his oldest friends he was described as being 'known by painters, sculptors, architects, and editors …Previously refused everywhere, he was now welcomed by everyone and exercised magnificently the profession he had chosen'.(8) His many versions of business cards, which allowed Atget to cater to various markets, attest to his diversity of clients. Between 19 November 1902 and 27 September 1904, the V&A was in correspondence with the photographer, and Atget's letters are preserved in the National Art Library at the Museum. His business card from 1902 accompanying the V&A correspondence describes the photographer as 'Auteur-éditeur' of a series of photographs of 'Old Paris - Monuments and Views'.(9) Atget would have known, most probably from one of his French institutional clients, that the Museum's library owned one of the largest reference collections of photographs of works of art and architecture, and between 1903 and 1905 he sent parcels containing hundreds of photographs to the V&A. The correspondence outlines the nature of his inventory and quotes a rate for each photograph of 1 franc, and 1 franc 25 centimes for images which involved travel to the environs. He concluded his initial correspondence with references to his French institutional clients such as the Bibliothèque Nationale and the Musée Carnavalet. The correspondence abruptly ends in 1905 and it is not clear why the relationship between the Museum and Atget ended. The V&A purchased close to 600 photographs directly from Atget for the National Art Library. They would have been intended for use by historians and students to study at a time when photo mechanically illustrated books were not widely available. Once acquired, they were filed under place names or sometimes object name - for example, 'Paris: Decorative Ironwork' or 'Door Knocker, House No. 4 Rue Poultier, Paris'. The photographs purchased directly from Atget in the V&A collection include examples of notable public buildings, churches, fountains, shop fronts, staircases, doorknockers, wood carvings, sculpture gardens, wrought iron, shop signs, fresco paintings, and the environs of Paris. The prints are all marked with the National Art Library blindstamp and mounted on green card with the location and object description noted in pen on the mount. Atget continued to do business with his other institutional clients but with the outbreak of war in 1914, rations, and shells falling in Luxembourg Gardens, production dwindled, and Atget stored his glass negatives in the basement of his building. There is no record of new photographs taken by Atget during the last two years of the War. After the War, interest in Atget's subject waned. Old Paris, was no longer a priority, as the city focussed on reconstruction efforts. In the autumn of 1920, he sold 2600 glass plate negatives to the French State for 10,000 francs, which later became part of the collection of the Service Photographique des Monuments Historiques. In his offering letter of 12 November, 1920, Atget described his images as 'artistic documents of beautiful urban architecture from the 16th to the 19th centuries'.10 However, this was not the end of Atget's career. Whether spurred by the atrocities of the War, his advancing years, the declining public interest in his previous subject matter, or the financial freedom that the sale of the negatives provided, Atget's style shifted to one that was more personal and allegorical and most critics agree that it was during this period that Atget produced his most subjective works. To achieve this effect, Atget altered his working practice. Rather than shooting when the sun was high, avoiding the long shadows of early morning and late afternoon, he would often start work at first dawn or late in the day when conditions might produce an image that was more 'pictorial' in style. He returned to previously photographed sites which now held personal symbolism for him, and he pursued themes which referenced death, decay and the passage of time. In 1926, Atget's companion, Valentine died. Atget himself died a little more than one year later, on the 4th August 1927. Throughout his career, Atget firmly embraced the milieu of the archive and rejected any artistic self-consciousness. He failed to join the numerous photo clubs or societies that flourished with the expansion of the medium. He insisted more than once to Man Ray that his job was to provide 'documents, documents for artists'.(11) Most critics agree that Atget was likely aware of the aspirations made for the medium by his contemporaries in Europe and America, specifically by the Linked Ring and Photo Succession movements, who sought to promote pictorialism and photography as a fine art.(12 ) Nonetheless, Atget eschewed any 'artistic pretensions' when presenting his sample copies to potential clients, using torn and mended prints and reusing album covers. Such presentation announced their status as simply catalogues of content that could be modified to suit a wide range of clients. At one point during the time that the artist was in correspondence with the V&A, the Museum asked for a quote for photographs produced in the more stable platinotype process. Atget refused, explaining that his workshop was not set up to produce anything but albumen prints for libraries, artists and editors to use for phototype and photogravure methods of reproduction.(13) In this way, Atget insisted upon his status as the document maker, resisting the more expensive plantinotype process, which was later often associated with art photography. A shift in perception about Atget's work began in the last years of his life, when he met Berenice Abbott (1898-1991), a young American working in Paris for the photographer Man Ray. Abbott was entranced by the strangeness, whether intentional or not, of his photographs, seeing in them a Surrealist vein as well as a relentless fidelity to fact and a deep love of the subject for its own sake.(14) Seen through the filter of Surrealism, this strangeness asserts itself; very few people actually appear in Atget's work, though there is evidence of habitation - reflections in windows, abandoned wheelbarrows on cobbled streets, blurred outlines, shadows. These traces become a eulogy to absence. It is what the aesthetic theorist Walter Benjamin was referencing when he wrote: 'Not for nothing were pictures of Atget compared with those of the scene of a crime'.(15) After Atget's death in 1927, Abbott bought the remains of his archive and she began to promote his images, reprinting his work using the original negatives. In 1930, she published a book of Atget's photographs, Atget: Photographe de Paris, which established Atget as a Modernist. Atget's reputation as a Modernist was cemented by John Szarkowski (1925-2007), the influential director of the department of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Atget's definition as a Modernist was crucial to the influential MoMA curator's view that photography was a unique medium with its own aesthetic that differentiates it from other visual art-forms. Szarkowski, along with the curator Maria Morris Hambourg, eventually mounted four landmark exhibitions along with publications of the photographer's work. More recently, no single view of the elusive photographer can be claimed. Atget scholarship has shifted from traditional authoritative interpretations towards more historical and political readings, often focussing on the status of the archive and influenced by the theories of the philosopher Michel Foucault. These revisionist views only add to the questions surrounding Atget and his work.(16) The V&A's collection provides an interesting platform for the study of the evolving scholarship on Atget and more broadly the changing perceptions of photography as a fine art and its place within today's museums. When the Museum first acquired the works from Atget, they became part of the collection of the National Art Library, as models for 'all variety of workers'.(17) Denied a place among the curatorial departments of the Museum, a portfolio of Atget gelatin silver prints produced by Abbott in 1956 from Atget's original negatives were acquired in 1974 by the now-defunct Circulation Department, the V&A's travelling exhibitions program. But it was not until 1977 when the responsibility of the photography collection transferred from the National Art Library to the Department of Prints, Drawings and Paintings, where it was consolidated with all the photographs acquired by Circulation, that Atget, and the rest of the V&A's photography collection, became a successful part of the Museum's exhibition program. --Erika Lederman, based on "A Biography of Eugène Atget," by Maria Morris Hambourg in John Szarkowski & Maria Morris Hambourg, The Work of Atget: vol. II, The Art of Old Paris (New York: MoMA, 1982). 1 Maria Morris Hambourg, "A Biography of Eugène Atget" in Szarkowski and Hambourg, The Work of Atget: vol. II, The Art of Old Paris (New York: MoMA, 1981-85), 14. 2 Recounted by Man Ray to Paul Hill and Tom Cooper, "Interview: Man Ray," Camera 54 (February 1975), 40. 3 Hambourg, 11. 4 As cited by Hambourg (from the Archives Nationales), 11. 5 Ibid, 12. 6 As cited by Hambourg (from La Revue des beaux-arts), 14. 7 As cited by Hambourg (from the author's dissertation: "Eugène Atget, 1857-1927: The Structure of the Work"), 16. 8 From transcription of handwritten letter to Berenice Abbott from Atget's friend Andre Calmette in Berenice Abbott, The World of Atget (New York: Horizon Press, 1964), xii. 9 Eugène Atget, Letters and postcard: Paris to the Victoria and Albert Museum Library,1902-1904. NAL Pressmark 86.JJ Box I. 10 As cited by Hambourg (from Atget's offering letter to the Ministre des Beaux-Arts), 29. 11 Molly Nesbit, Atget's Seven Albums (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), 9. 12 Nesbit, 9. 13 Atget, letter dated 22 December 1902. 14 Abbott, xxv. 15 Walter Benjamin, "Short History of Photography," trans. Phil Patton, Artforum 15 (February 1977), 51. 16 See Rosalind Krauss, "Photography's Discursive Space," in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1985) 131-150 and Abigail Solomon-Godeau, "Canon Fodder: Authoring Eugene Atget," in Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 28-51. 17 Mark Haworth-Booth, Photography: An Independent Art (London: V&A Publications, 1997), 102. |

| Places depicted | |

| Summary | Eugène Atget (1857-1927) took up photography as a professional in the late 1880s. Details of his earlier life are shadowy. He is known to have been a sailor and then an amateur actor, which may account for the ‘stage set’ quality of many of his images. He seems to have lived a largely secluded life in his apartment in Paris. His project to record ‘Old Paris’ began around 1897 and continued until the 1920s. In it, Atget was driven by the disappearance of buildings as schemes of modernisation swept the city. Ignoring the grand new vistas, he set out to record the character and details of the timeworn streets. He made a stock of prints for sale to artists, museums and libraries, in France and abroad, selling some 600 prints directly to the V&A. Today, however, Atget is admired less as a record photographer and more as a forerunner of Surrealism and of modern approaches to the art of photography. His urban scenes - featuring snatched glimpses, tangential perspectives, odd reflections and bizarre details - convey a distinctly modern experience of the city. In 1936, critic Walter Benjamin described how these images operated beyond their ostensible purpose, appearing unintentionally, but uncannily, like the ‘scene of a crime’. This shift in perception about Atget’s work began in the last years of his life, when he met Berenice Abbott, a young American working in Paris for the photographer Man Ray. After his death, Abbott bought the remains of his archive and began to promote his work. She was entranced by the strangeness of Atget’s photographs, seeing in them a Surrealist vein as well as a ‘relentless fidelity to fact’ and a ‘deep love of the subject for its own sake’. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | PH.412-1903 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | October 24, 2015 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest