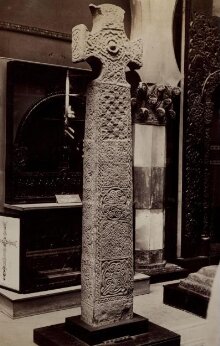

Standing Cross

ca. 1882 (made), 800-850 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Monumental standing stone crosses are some of the most important survivals of Anglo-Saxon sculpture, which dates from the 5th to the 11th centuries. In the mid-19th century, the Museum assembled a group of these crosses in the form of plaster cast copies, so that they could be more easily compared in one place. British scholars were keen to demonstrate that the decoration on crosses like these was distinct from art in mainland Europe.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Painted plaster cast |

| Brief description | Plaster cast of a standing cross made by Sergeant Bullen for the South Kensington Museum in London about 1882. The original was made in Irton, Cumbria in 800-850. |

| Physical description | Plaster cast of an Anglo-Saxon standing cross from the churchyard of St Paul's Chruch in Irton, Cumbria. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Production type | Copy |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | Cast of a standing cross in plaster made by Sergeant Bullen for the South Kensington Museum in about 1882. Standing crosses are some of the most important survivals of Anglo-Saxon sculpture and were cast so they could be compared in one place. The orginal cross was made by an unknown artist in Irton, Cumbria in 800-850. |

| Historical context | Making plaster copies is a centuries-old tradition that reached the height of its popularity during the 19th century. The V&A's casts are of large-scale architectural and sculptural works as well as small scale, jewelled book covers and ivory plaques, these last known as fictile ivories. The Museum commissioned casts directly from makers and acquired others in exchange. Oronzio Lelli, of Florence was a key overseas supplier while, in London, Giovanni Franchi and Domenico Brucciani upheld a strong Italian tradition as highly-skilled mould-makers, or formatori. Some casts are highly accurate depictions of original works, whilst others are more selective, replicating the outer surface of the original work, rather than its whole structure. Like a photograph, they record the moment the cast was taken: alterations, repairs and the wear and tear of age are all reproduced in the copies. The plasters can also be re-worked, so that their appearance differs slightly from the original from which they were taken. To make a plaster cast, a negative mould has to be taken of the original object. The initial mould could be made from one of several ways. A flexible mould could be made by mixing wax with gutta-percha, a rubbery latex product taken from tropical trees. These two substances formed a mould that had a slightly elastic quality, so that it could easily be removed from the original object. Moulds were also made from gelatine, plaster or clay, and could then be used to create a plaster mould to use for casting. When mixed with water, plaster can be poured into a prepared mould, allowed to set, and can be removed to produce a finished solid form. The moulds are coated with a separating or paring agent to prevent the newly poured plaster sticking to them. The smooth liquid state and slight expansion while setting allowed the quick drying plaster to infill even the most intricate contours of a mould. Flatter, smaller objects in low relief usually require only one mould to cast the object. For more complex objects, with a raised surface, the mould would have to be made from a number of sections, known as piece-moulds. These pieces are held together in the so-called mother-mould, in order to create a mould of the whole object. Once the object has been cast from this mother-mould, the piece-moulds can be easily removed one by one, to create a cast of the three-dimensional object. |

| Production | Northumbrian |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | Monumental standing stone crosses are some of the most important survivals of Anglo-Saxon sculpture, which dates from the 5th to the 11th centuries. In the mid-19th century, the Museum assembled a group of these crosses in the form of plaster cast copies, so that they could be more easily compared in one place. British scholars were keen to demonstrate that the decoration on crosses like these was distinct from art in mainland Europe. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | REPRO.1882-259 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 29, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest