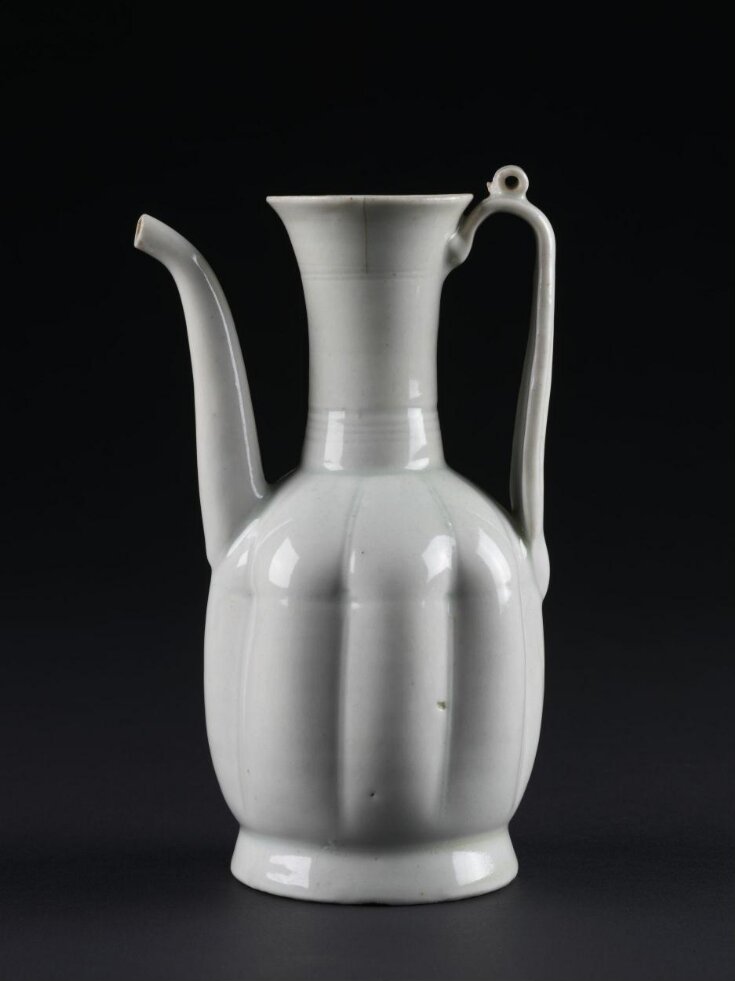

Ewer

960-1127 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This eight-lobed ewer was made in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, a town that was to dominate the entire porcelain industry in China for century to come.

The kilns of southern China, which had earlier excelled in making green ware, started to produce white ware in the ten century. The resultant Qingbai porcelains differ from their northern counterpart in both chemical composition and firing technique (see following entry for Northern Ding wares). They were fired in a 'dragon' kiln, so called because its narrow and upward-climbing structure resembles a dragon. Such kilns were built into the side of a hill or a man-made mound and were designed to maximize heat from the fuel, which in this case was wood. Qingbai wares were fired in a reducing atmosphere, meaning the kiln was deliberately deprived of oxygen, resulting in a distinctive glassy, cool, bluish-white glaze. In Chinese, 'Qingbai' means literally 'bluish white'.

Like other whiteware, the ewer was made as a substitute for a silver vessel. Other daily not used to dining were also made in Qingbai porcelain, including lamps, pillows, incense burners, boxes and small jars. Qingbai ware was evidently an important export line from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, as examples have been found in Korea, Japan, South and South-East Asia, West Asia and North Africa. One of the earliest pieces of Chinese porcelain to reach Europe, the Fonthill vase (now in the National Museum of Ireland and once owned by a fourteenth-century king of Hungary) is of Qingbai ware.

The kilns of southern China, which had earlier excelled in making green ware, started to produce white ware in the ten century. The resultant Qingbai porcelains differ from their northern counterpart in both chemical composition and firing technique (see following entry for Northern Ding wares). They were fired in a 'dragon' kiln, so called because its narrow and upward-climbing structure resembles a dragon. Such kilns were built into the side of a hill or a man-made mound and were designed to maximize heat from the fuel, which in this case was wood. Qingbai wares were fired in a reducing atmosphere, meaning the kiln was deliberately deprived of oxygen, resulting in a distinctive glassy, cool, bluish-white glaze. In Chinese, 'Qingbai' means literally 'bluish white'.

Like other whiteware, the ewer was made as a substitute for a silver vessel. Other daily not used to dining were also made in Qingbai porcelain, including lamps, pillows, incense burners, boxes and small jars. Qingbai ware was evidently an important export line from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, as examples have been found in Korea, Japan, South and South-East Asia, West Asia and North Africa. One of the earliest pieces of Chinese porcelain to reach Europe, the Fonthill vase (now in the National Museum of Ireland and once owned by a fourteenth-century king of Hungary) is of Qingbai ware.

Delve deeper

Discover more about this object

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Porcelain with clear glaze |

| Brief description | Cer, China, Song, qingbai ware, timeline |

| Physical description | This eight-lobed ewer was made in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, a town that was to dominate the entire porcelain industry in China for century to come. The kilns of southern China, which had earlier excelled in making green ware, started to produce white ware in the ten century. The resultant Qingbai porcelains differ from their northern counterpart in both chemical composition and firing technique (see following entry for Northern Ding wares). They were fired in a 'dragon' kiln, so called because its narrow and upward-climbing structure resembles a dragon. Such kilns were built into the side of a hill or a man-made mound and were designed to maximize heat from the fuel, which in this case was wood. Qingbai wares were fired in a reducing atmosphere, meaning the kiln was deliberately deprived of oxygen, resulting in a distinctive glassy, cool, bluish-white glaze. In Chinese, 'Qingbai' means literally 'bluish white'. Like other whiteware, the ewer was made as a substitute for a silver vessel. Other daily not used to dining were also made in Qingbai porcelain, including lamps, pillows, incense burners, boxes and small jars. Qingbai ware was evidently an important export line from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, as examples have been found in Korea, Japan, South and South-East Asia, West Asia and North Africa. One of the earliest pieces of Chinese porcelain to reach Europe, the Fonthill vase (now in the National Museum of Ireland and once owned by a fourteenth-century king of Hungary) is of Qingbai ware. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Styles | |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | H.B. Harris Bequest |

| Production | 11th century (Kerr 2004: 96) |

| Summary | This eight-lobed ewer was made in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, a town that was to dominate the entire porcelain industry in China for century to come. The kilns of southern China, which had earlier excelled in making green ware, started to produce white ware in the ten century. The resultant Qingbai porcelains differ from their northern counterpart in both chemical composition and firing technique (see following entry for Northern Ding wares). They were fired in a 'dragon' kiln, so called because its narrow and upward-climbing structure resembles a dragon. Such kilns were built into the side of a hill or a man-made mound and were designed to maximize heat from the fuel, which in this case was wood. Qingbai wares were fired in a reducing atmosphere, meaning the kiln was deliberately deprived of oxygen, resulting in a distinctive glassy, cool, bluish-white glaze. In Chinese, 'Qingbai' means literally 'bluish white'. Like other whiteware, the ewer was made as a substitute for a silver vessel. Other daily not used to dining were also made in Qingbai porcelain, including lamps, pillows, incense burners, boxes and small jars. Qingbai ware was evidently an important export line from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, as examples have been found in Korea, Japan, South and South-East Asia, West Asia and North Africa. One of the earliest pieces of Chinese porcelain to reach Europe, the Fonthill vase (now in the National Museum of Ireland and once owned by a fourteenth-century king of Hungary) is of Qingbai ware. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | C.112-1929 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 21, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest