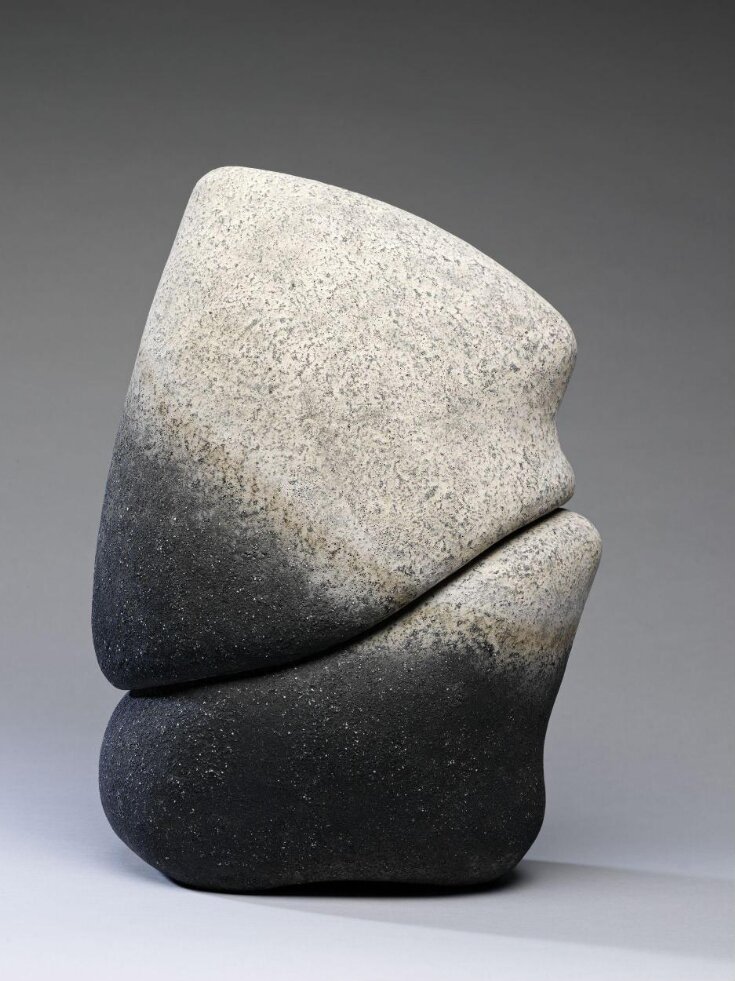

Covered Vessel no. 7

Sculpture

2012 (made)

2012 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Essay from the two-person exhibition in New York at which this work by Gomi Kenji was exhibited.

Izumita Yukiya and Gomi Kenji

Materiality, form, colour – movement, monumentality and enclosure. The opportunity to see the very different works of Izumita Yukiya (1966-) and Gomi Kenji (1978-) juxtaposed in the same space promises to be a visceral and haunting experience. Izumita, the elder of the two artists, has been exhibited in the USA before - at SOFA, New York in 2005 and more recently at the Touching Stone Gallery in Santa Fe in April-May 2011. For Gomi, who is still in his early 30s, this is the first showing of his work outside Asia.

The first time I saw Izumita’s work was at the World Crafts Competition, Kanazawa in 2001, which was not long after he had begun wood-firing in an anagama kiln, a practice he continues to this day. In the case of Gomi, I remember the prize-winning work he submitted to the 7th Mashiko Ceramics Competition in 2007. This was of a scale and format similar to the works shown here, but it was more brightly coloured in shades of grey and blue. His recent preference for black, grey and white, also seen in the piece selected for last year’s 9th International Ceramics Competition Mino, reveals an intensification of purpose indicative of his growing maturity.

It is interesting that both artists eschew the use of artificial glazes, preferring to let the mineral oxides within the clay react with the flames of the kiln to produce colour schemes reminiscent of primitive pottery. Izumita makes use of the full range of oxidisation-to-reduction orange-to-black. Gomi, on the other hand, works only with the cooler effects of reduction firing. While chance plays its role, it is evident that both artists are very much in control of what takes place within their respective kilns.

The elimination of glazes allows Gomi and Izumita to explore the materiality of clay with direct immediacy. Much time is clearly spent mixing materials to produce the textures that are such powerfully defining aspects of their work. Although similar in this respect, their ceramics are almost diametrically opposed in terms of what one might call their musicality. Izumita’s sharp-edged forms twist and roll, rise and slide like the impossible-to-finger notes of a Bach partita. Gomi’s forms, by contrast, are weighty, majestic and charged with a spirituality reminiscent of a Brucknerian adagio.

On the question of spirituality or religiosity, I was struck by the fact that Gomi received his training as a ceramicist at the Tsuboya kilns in Okinawa, home of the iconic jiishigami or funeral urn. Lifting the lid from a Gomi vessel, which I have done on the two occasions I have encountered his work, is like taking off the cover of a jiishigami – trepidation at handling something so heavy and fragile mixed with awe at the dull-ringing interior void, receptacle for the washed bones of the dead. Gomi’s forms have none of the elaborate modelling of Okinawan jiishigami, but they convey a strong sense of something similarly otherworldly and strange.

Izumita’s works are compelling less for their quietude than the dynamism of their folded and curved, surface-rich forms. On the other hand, and this is evident from the titles he uses and statements he has made about his work, he is interested in the slow, long-term workings of nature, whether the erosion of the sea shore through the action of waves or the more dramatic upheavals caused by typhoons and volcanic eruptions. In this regard there is a sad poetry in the fact that Izumita was born in Rikuzentakata, one of the many coastal towns devastated by the tsunami that followed the Tōhoku earthquake of 11 March 2011, and lives and works less than a hundred miles to the north.

This may be reading too much into the exhibition, but for me its combination of the work of an artist who experienced first hand the tragedy of March 2011 with that of a maker whose work speaks so eloquently of death and the afterlife makes for a lamentation of the most poignant kind.

Izumita Yukiya and Gomi Kenji

Materiality, form, colour – movement, monumentality and enclosure. The opportunity to see the very different works of Izumita Yukiya (1966-) and Gomi Kenji (1978-) juxtaposed in the same space promises to be a visceral and haunting experience. Izumita, the elder of the two artists, has been exhibited in the USA before - at SOFA, New York in 2005 and more recently at the Touching Stone Gallery in Santa Fe in April-May 2011. For Gomi, who is still in his early 30s, this is the first showing of his work outside Asia.

The first time I saw Izumita’s work was at the World Crafts Competition, Kanazawa in 2001, which was not long after he had begun wood-firing in an anagama kiln, a practice he continues to this day. In the case of Gomi, I remember the prize-winning work he submitted to the 7th Mashiko Ceramics Competition in 2007. This was of a scale and format similar to the works shown here, but it was more brightly coloured in shades of grey and blue. His recent preference for black, grey and white, also seen in the piece selected for last year’s 9th International Ceramics Competition Mino, reveals an intensification of purpose indicative of his growing maturity.

It is interesting that both artists eschew the use of artificial glazes, preferring to let the mineral oxides within the clay react with the flames of the kiln to produce colour schemes reminiscent of primitive pottery. Izumita makes use of the full range of oxidisation-to-reduction orange-to-black. Gomi, on the other hand, works only with the cooler effects of reduction firing. While chance plays its role, it is evident that both artists are very much in control of what takes place within their respective kilns.

The elimination of glazes allows Gomi and Izumita to explore the materiality of clay with direct immediacy. Much time is clearly spent mixing materials to produce the textures that are such powerfully defining aspects of their work. Although similar in this respect, their ceramics are almost diametrically opposed in terms of what one might call their musicality. Izumita’s sharp-edged forms twist and roll, rise and slide like the impossible-to-finger notes of a Bach partita. Gomi’s forms, by contrast, are weighty, majestic and charged with a spirituality reminiscent of a Brucknerian adagio.

On the question of spirituality or religiosity, I was struck by the fact that Gomi received his training as a ceramicist at the Tsuboya kilns in Okinawa, home of the iconic jiishigami or funeral urn. Lifting the lid from a Gomi vessel, which I have done on the two occasions I have encountered his work, is like taking off the cover of a jiishigami – trepidation at handling something so heavy and fragile mixed with awe at the dull-ringing interior void, receptacle for the washed bones of the dead. Gomi’s forms have none of the elaborate modelling of Okinawan jiishigami, but they convey a strong sense of something similarly otherworldly and strange.

Izumita’s works are compelling less for their quietude than the dynamism of their folded and curved, surface-rich forms. On the other hand, and this is evident from the titles he uses and statements he has made about his work, he is interested in the slow, long-term workings of nature, whether the erosion of the sea shore through the action of waves or the more dramatic upheavals caused by typhoons and volcanic eruptions. In this regard there is a sad poetry in the fact that Izumita was born in Rikuzentakata, one of the many coastal towns devastated by the tsunami that followed the Tōhoku earthquake of 11 March 2011, and lives and works less than a hundred miles to the north.

This may be reading too much into the exhibition, but for me its combination of the work of an artist who experienced first hand the tragedy of March 2011 with that of a maker whose work speaks so eloquently of death and the afterlife makes for a lamentation of the most poignant kind.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Title | Covered Vessel no. 7 (assigned by artist) |

| Materials and techniques | Hand-built and reduction-fired earthenware |

| Brief description | Sculptural form, 'Covered Vessel no. 7', unglazed earthenware, 2012, by Gomi Kenji (1978-) Japan, modern crafts, studio, ceramics |

| Physical description | Upright two-part form of rounded profile consisting of a squat base and a tall lid. The fired clay varies in colour from dark grey at the bottom to ash white at the top, the transition form dark to light being dramatically marked by a diagonal band around the lower part of the lid. The base and lid are both hollow and have pierced airholes on their interiors. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Gift of Harumi Yanagi Contemporary Ceramics |

| Summary | Essay from the two-person exhibition in New York at which this work by Gomi Kenji was exhibited. Izumita Yukiya and Gomi Kenji Materiality, form, colour – movement, monumentality and enclosure. The opportunity to see the very different works of Izumita Yukiya (1966-) and Gomi Kenji (1978-) juxtaposed in the same space promises to be a visceral and haunting experience. Izumita, the elder of the two artists, has been exhibited in the USA before - at SOFA, New York in 2005 and more recently at the Touching Stone Gallery in Santa Fe in April-May 2011. For Gomi, who is still in his early 30s, this is the first showing of his work outside Asia. The first time I saw Izumita’s work was at the World Crafts Competition, Kanazawa in 2001, which was not long after he had begun wood-firing in an anagama kiln, a practice he continues to this day. In the case of Gomi, I remember the prize-winning work he submitted to the 7th Mashiko Ceramics Competition in 2007. This was of a scale and format similar to the works shown here, but it was more brightly coloured in shades of grey and blue. His recent preference for black, grey and white, also seen in the piece selected for last year’s 9th International Ceramics Competition Mino, reveals an intensification of purpose indicative of his growing maturity. It is interesting that both artists eschew the use of artificial glazes, preferring to let the mineral oxides within the clay react with the flames of the kiln to produce colour schemes reminiscent of primitive pottery. Izumita makes use of the full range of oxidisation-to-reduction orange-to-black. Gomi, on the other hand, works only with the cooler effects of reduction firing. While chance plays its role, it is evident that both artists are very much in control of what takes place within their respective kilns. The elimination of glazes allows Gomi and Izumita to explore the materiality of clay with direct immediacy. Much time is clearly spent mixing materials to produce the textures that are such powerfully defining aspects of their work. Although similar in this respect, their ceramics are almost diametrically opposed in terms of what one might call their musicality. Izumita’s sharp-edged forms twist and roll, rise and slide like the impossible-to-finger notes of a Bach partita. Gomi’s forms, by contrast, are weighty, majestic and charged with a spirituality reminiscent of a Brucknerian adagio. On the question of spirituality or religiosity, I was struck by the fact that Gomi received his training as a ceramicist at the Tsuboya kilns in Okinawa, home of the iconic jiishigami or funeral urn. Lifting the lid from a Gomi vessel, which I have done on the two occasions I have encountered his work, is like taking off the cover of a jiishigami – trepidation at handling something so heavy and fragile mixed with awe at the dull-ringing interior void, receptacle for the washed bones of the dead. Gomi’s forms have none of the elaborate modelling of Okinawan jiishigami, but they convey a strong sense of something similarly otherworldly and strange. Izumita’s works are compelling less for their quietude than the dynamism of their folded and curved, surface-rich forms. On the other hand, and this is evident from the titles he uses and statements he has made about his work, he is interested in the slow, long-term workings of nature, whether the erosion of the sea shore through the action of waves or the more dramatic upheavals caused by typhoons and volcanic eruptions. In this regard there is a sad poetry in the fact that Izumita was born in Rikuzentakata, one of the many coastal towns devastated by the tsunami that followed the Tōhoku earthquake of 11 March 2011, and lives and works less than a hundred miles to the north. This may be reading too much into the exhibition, but for me its combination of the work of an artist who experienced first hand the tragedy of March 2011 with that of a maker whose work speaks so eloquently of death and the afterlife makes for a lamentation of the most poignant kind. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | FE.59-2012 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | August 30, 2013 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest