The Walrus and the Carpenter

Wood-Engraving

1872 (made)

1872 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

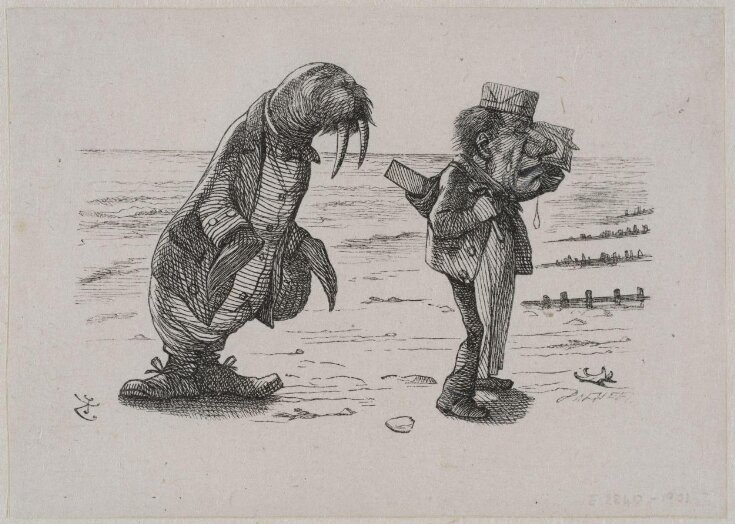

Tenniel was essentially self-taught, but his drawings to illustrate Carroll's Alice books owe much to the work of the French caricaturist and illustrator Grandville (1803-47), especially his comic animal imagery of the 1830s. Tenniel's illustrations to Through the looking-glass include many of his most memorable inventions such as Humpty Dumpty, Jabberwocky, and the two characters seen here, the Walrus and the Carpenter. Here they are shown wandering along a beach, having lured the 'little oysters' and then eaten them.

In the story, the characters Tweedledum and Tweedledee tell Alice a story about the ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’. This verse parodies a well-known cautionary tale called ‘The Spider and the Fly’, which warns against trusting strangers who use flattery to disguise their true intentions. The young oysters, tempted away from their bed by the Walrus and Carpenter, met a similar tragic fate to the fly of the original source material.

These proofs and partial pulls are wood engravings illustrating the second of Lewlis Carroll's storybooks about Alice, Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there', published in 1872.

The first of the two storybooks Alice's adventures in Wonderland originated a decade earlier during a boat trip. One ‘golden afternoon’ in July 1862, according to legend, Charles Dodgson, mathematics teacher at Christ Church College, Oxford University, rowed up the river Thames from Oxford to Godstow for a picnic with his friend Robinson Duckworth and Alice, Edith and Lorina Liddell, the daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church College. On the way, he told a story to entertain his companions. Alice begged Dodgson to write the story down for her as a keepsake, and the first version of 'Alice’s adventures under ground' still survives in a manuscript (in the British Library), which Dodgson presented to Alice for Christmas in 1864. In a diary entry sometime later, the writer described how he and a friend ‘took the three Liddells up to Godstow’ again and ‘had to go on with my interminable fairy-tale of “Alice’s Adventures”’. This exasperated report suggests that while the story of the single ‘golden afternoon’ has become part of literary legend, there may have been more than a few storytelling occasions.

Dodgson worked with the publisher Macmillan & Co. and the acclaimed illustrator John Tenniel to create the published edition of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland. Tenniel’s interpretations of the characters helped to establish the success of the book, and of its sequel Through the looking-glass.

On the suggestion of his friend, the fantasy writer George Macdonald, Dodgson decided to publish his Alice story in 1863. He took the pen name Lewis Carroll, formed from a reversed Latin version of his first and middle names, Charles Lutwidge (Ludovic Carolus). The book was eventually published in November 1865. An unproven author, Dodgson took on all of the risk for the publication. Having created his own manuscript, at first he intended to illustrate the published book himself, spending over two years preparing his imagery. Eventually, though, he commissioned acclaimed illustrator John Tenniel. Carroll and Tenniel, both perfectionists, drew up detailed plans to agree the subjects, placement and size of the book’s many illustrations. Tenniel drew rough sketches on paper before transferring his finished drawings directly onto woodblocks, which were then engraved by the Dalziel Brothers, a prominent word engraving firm. After a false start, which saw two thousand copies of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland rejected for their poor printing quality (copies survive in a US published version), and a new printer Richard Clay appointed, Carroll declared the reprint: ‘a perfect piece of artistic printing’.

When Alice’s adventures in Wonderland appeared, reviewers described the book as ‘delicious nonsense’, noting its appeal both to adults and children. Carroll had a ‘floating idea of writing a sort of sequel’, which he called ‘Looking-Glass House’ as early as August 1866, but Tenniel was busy. The pair began discussing plans for the new illustrations in 1869. Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there eventually appeared on 6 December 1871. It was highly rated and rekindled interest in the first story, causing sales of the earlier book to double within a year. Tenniel’s illustrations for the second book established what has become Alice’s iconic and much imitated look, including her striped stockings and hairband.

The Looking-glass story follows an eccentric version of a game of chess. At the start of the book is a list of the characters, each relating to a chess piece, with Alice a white pawn. In the story, she passes through a chequered landscape of fields separated by brooks, which she must cross to change squares. Carroll enjoyed playing with logic and inventing alternative rules to games. In Looking-glass the rules of the chess game reflect the logic of the narrative rather than chess as we know it today.

In the story, the characters Tweedledum and Tweedledee tell Alice a story about the ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’. This verse parodies a well-known cautionary tale called ‘The Spider and the Fly’, which warns against trusting strangers who use flattery to disguise their true intentions. The young oysters, tempted away from their bed by the Walrus and Carpenter, met a similar tragic fate to the fly of the original source material.

These proofs and partial pulls are wood engravings illustrating the second of Lewlis Carroll's storybooks about Alice, Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there', published in 1872.

The first of the two storybooks Alice's adventures in Wonderland originated a decade earlier during a boat trip. One ‘golden afternoon’ in July 1862, according to legend, Charles Dodgson, mathematics teacher at Christ Church College, Oxford University, rowed up the river Thames from Oxford to Godstow for a picnic with his friend Robinson Duckworth and Alice, Edith and Lorina Liddell, the daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church College. On the way, he told a story to entertain his companions. Alice begged Dodgson to write the story down for her as a keepsake, and the first version of 'Alice’s adventures under ground' still survives in a manuscript (in the British Library), which Dodgson presented to Alice for Christmas in 1864. In a diary entry sometime later, the writer described how he and a friend ‘took the three Liddells up to Godstow’ again and ‘had to go on with my interminable fairy-tale of “Alice’s Adventures”’. This exasperated report suggests that while the story of the single ‘golden afternoon’ has become part of literary legend, there may have been more than a few storytelling occasions.

Dodgson worked with the publisher Macmillan & Co. and the acclaimed illustrator John Tenniel to create the published edition of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland. Tenniel’s interpretations of the characters helped to establish the success of the book, and of its sequel Through the looking-glass.

On the suggestion of his friend, the fantasy writer George Macdonald, Dodgson decided to publish his Alice story in 1863. He took the pen name Lewis Carroll, formed from a reversed Latin version of his first and middle names, Charles Lutwidge (Ludovic Carolus). The book was eventually published in November 1865. An unproven author, Dodgson took on all of the risk for the publication. Having created his own manuscript, at first he intended to illustrate the published book himself, spending over two years preparing his imagery. Eventually, though, he commissioned acclaimed illustrator John Tenniel. Carroll and Tenniel, both perfectionists, drew up detailed plans to agree the subjects, placement and size of the book’s many illustrations. Tenniel drew rough sketches on paper before transferring his finished drawings directly onto woodblocks, which were then engraved by the Dalziel Brothers, a prominent word engraving firm. After a false start, which saw two thousand copies of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland rejected for their poor printing quality (copies survive in a US published version), and a new printer Richard Clay appointed, Carroll declared the reprint: ‘a perfect piece of artistic printing’.

When Alice’s adventures in Wonderland appeared, reviewers described the book as ‘delicious nonsense’, noting its appeal both to adults and children. Carroll had a ‘floating idea of writing a sort of sequel’, which he called ‘Looking-Glass House’ as early as August 1866, but Tenniel was busy. The pair began discussing plans for the new illustrations in 1869. Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there eventually appeared on 6 December 1871. It was highly rated and rekindled interest in the first story, causing sales of the earlier book to double within a year. Tenniel’s illustrations for the second book established what has become Alice’s iconic and much imitated look, including her striped stockings and hairband.

The Looking-glass story follows an eccentric version of a game of chess. At the start of the book is a list of the characters, each relating to a chess piece, with Alice a white pawn. In the story, she passes through a chequered landscape of fields separated by brooks, which she must cross to change squares. Carroll enjoyed playing with logic and inventing alternative rules to games. In Looking-glass the rules of the chess game reflect the logic of the narrative rather than chess as we know it today.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Walrus and the Carpenter (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | Wood engraving, proof on India paper |

| Brief description | Print, wood engraved illustration to Through the Looking-Glass, and what Alice found there, engraved by Dalziel Brothers after Sir John Tenniel, 1871. |

| Physical description | Illustration to Alice Through the Looking-Glass. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | Illustration to 'Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice found there' by Lewis carroll, 1872. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Literary reference | Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, Lewis Carroll (London: Macmillan, 1872) |

| Summary | Tenniel was essentially self-taught, but his drawings to illustrate Carroll's Alice books owe much to the work of the French caricaturist and illustrator Grandville (1803-47), especially his comic animal imagery of the 1830s. Tenniel's illustrations to Through the looking-glass include many of his most memorable inventions such as Humpty Dumpty, Jabberwocky, and the two characters seen here, the Walrus and the Carpenter. Here they are shown wandering along a beach, having lured the 'little oysters' and then eaten them. In the story, the characters Tweedledum and Tweedledee tell Alice a story about the ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’. This verse parodies a well-known cautionary tale called ‘The Spider and the Fly’, which warns against trusting strangers who use flattery to disguise their true intentions. The young oysters, tempted away from their bed by the Walrus and Carpenter, met a similar tragic fate to the fly of the original source material. These proofs and partial pulls are wood engravings illustrating the second of Lewlis Carroll's storybooks about Alice, Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there', published in 1872. The first of the two storybooks Alice's adventures in Wonderland originated a decade earlier during a boat trip. One ‘golden afternoon’ in July 1862, according to legend, Charles Dodgson, mathematics teacher at Christ Church College, Oxford University, rowed up the river Thames from Oxford to Godstow for a picnic with his friend Robinson Duckworth and Alice, Edith and Lorina Liddell, the daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church College. On the way, he told a story to entertain his companions. Alice begged Dodgson to write the story down for her as a keepsake, and the first version of 'Alice’s adventures under ground' still survives in a manuscript (in the British Library), which Dodgson presented to Alice for Christmas in 1864. In a diary entry sometime later, the writer described how he and a friend ‘took the three Liddells up to Godstow’ again and ‘had to go on with my interminable fairy-tale of “Alice’s Adventures”’. This exasperated report suggests that while the story of the single ‘golden afternoon’ has become part of literary legend, there may have been more than a few storytelling occasions. Dodgson worked with the publisher Macmillan & Co. and the acclaimed illustrator John Tenniel to create the published edition of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland. Tenniel’s interpretations of the characters helped to establish the success of the book, and of its sequel Through the looking-glass. On the suggestion of his friend, the fantasy writer George Macdonald, Dodgson decided to publish his Alice story in 1863. He took the pen name Lewis Carroll, formed from a reversed Latin version of his first and middle names, Charles Lutwidge (Ludovic Carolus). The book was eventually published in November 1865. An unproven author, Dodgson took on all of the risk for the publication. Having created his own manuscript, at first he intended to illustrate the published book himself, spending over two years preparing his imagery. Eventually, though, he commissioned acclaimed illustrator John Tenniel. Carroll and Tenniel, both perfectionists, drew up detailed plans to agree the subjects, placement and size of the book’s many illustrations. Tenniel drew rough sketches on paper before transferring his finished drawings directly onto woodblocks, which were then engraved by the Dalziel Brothers, a prominent word engraving firm. After a false start, which saw two thousand copies of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland rejected for their poor printing quality (copies survive in a US published version), and a new printer Richard Clay appointed, Carroll declared the reprint: ‘a perfect piece of artistic printing’. When Alice’s adventures in Wonderland appeared, reviewers described the book as ‘delicious nonsense’, noting its appeal both to adults and children. Carroll had a ‘floating idea of writing a sort of sequel’, which he called ‘Looking-Glass House’ as early as August 1866, but Tenniel was busy. The pair began discussing plans for the new illustrations in 1869. Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there eventually appeared on 6 December 1871. It was highly rated and rekindled interest in the first story, causing sales of the earlier book to double within a year. Tenniel’s illustrations for the second book established what has become Alice’s iconic and much imitated look, including her striped stockings and hairband. The Looking-glass story follows an eccentric version of a game of chess. At the start of the book is a list of the characters, each relating to a chess piece, with Alice a white pawn. In the story, she passes through a chequered landscape of fields separated by brooks, which she must cross to change squares. Carroll enjoyed playing with logic and inventing alternative rules to games. In Looking-glass the rules of the chess game reflect the logic of the narrative rather than chess as we know it today. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | E.2840-1901 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | July 25, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest