Mourning Ring

1550-1600 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

A devout Christian in sixteenth century Europe would be conscious of the fragility of life and the ever present threat of death, through disease, accident or if lucky, old age. Christians therefore felt the need to prepare their souls for everlasting judgment through prayer and reflection. 'Memento mori' (remember you must die) inscriptions and devices such as hourglasses, skulls, crossbones and skeletons became fashionable on many types of jewellery. A ring worn on the finger would be a daily reminder to prepare for life in the world to come. Rings decorated with this funereal imagery were also left in wills to family and friends.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the practice of bequeathing rings belonging to the deceased to friends and family was gradually replaced by the custom of leaving a sum of money to buy commemorative and mourning rings. Later in the seventeenth century, rings were distributed at the funeral service to be worn in memory of the deceased.

The inscription on this ring reads: 'Nosse te psum', a variation on 'Nosce te ipsum' or 'know yourself', which was a popular motto on memento mori jewellery. In 1617, the will of Nicholas Fenay of Yorkshire describes a ring which was to be left to his son:

'having these letters NF for my name thereupon ingraved with this notable poesie about the same letters NOSCE TEIPSUM [sic know thyself] to the intent that my said son William Fenay in the often beholding and considering of that worthy poesye may be the better put in mynde of himselfe and of his estate knowing this that to know a man's selfe is the beginning of wisdom'. The inscription 'Dye to lyve' refers to the need to give up earthly life in favour of eternal life in Heaven.

This ring forms part of a collection of 760 rings and engraved gems from the collection of Edmund Waterton (1830-87). Waterton was one of the foremost ring collectors of the nineteenth century and was the author of several articles on rings, a book on English devotion to the Virgin Mary and an unfinished catalogue of his collection (the manuscript is now the National Art Library). Waterton was noted for his extravagance and financial troubles caused him to place his collection in pawn with the London jeweller Robert Phillips. When he was unable to repay the loan, Phillips offered to sell the collection to the Museum and it was acquired in 1871. A small group of rings which Waterton had held back were acquired in 1899.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the practice of bequeathing rings belonging to the deceased to friends and family was gradually replaced by the custom of leaving a sum of money to buy commemorative and mourning rings. Later in the seventeenth century, rings were distributed at the funeral service to be worn in memory of the deceased.

The inscription on this ring reads: 'Nosse te psum', a variation on 'Nosce te ipsum' or 'know yourself', which was a popular motto on memento mori jewellery. In 1617, the will of Nicholas Fenay of Yorkshire describes a ring which was to be left to his son:

'having these letters NF for my name thereupon ingraved with this notable poesie about the same letters NOSCE TEIPSUM [sic know thyself] to the intent that my said son William Fenay in the often beholding and considering of that worthy poesye may be the better put in mynde of himselfe and of his estate knowing this that to know a man's selfe is the beginning of wisdom'. The inscription 'Dye to lyve' refers to the need to give up earthly life in favour of eternal life in Heaven.

This ring forms part of a collection of 760 rings and engraved gems from the collection of Edmund Waterton (1830-87). Waterton was one of the foremost ring collectors of the nineteenth century and was the author of several articles on rings, a book on English devotion to the Virgin Mary and an unfinished catalogue of his collection (the manuscript is now the National Art Library). Waterton was noted for his extravagance and financial troubles caused him to place his collection in pawn with the London jeweller Robert Phillips. When he was unable to repay the loan, Phillips offered to sell the collection to the Museum and it was acquired in 1871. A small group of rings which Waterton had held back were acquired in 1899.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Enamelled gold |

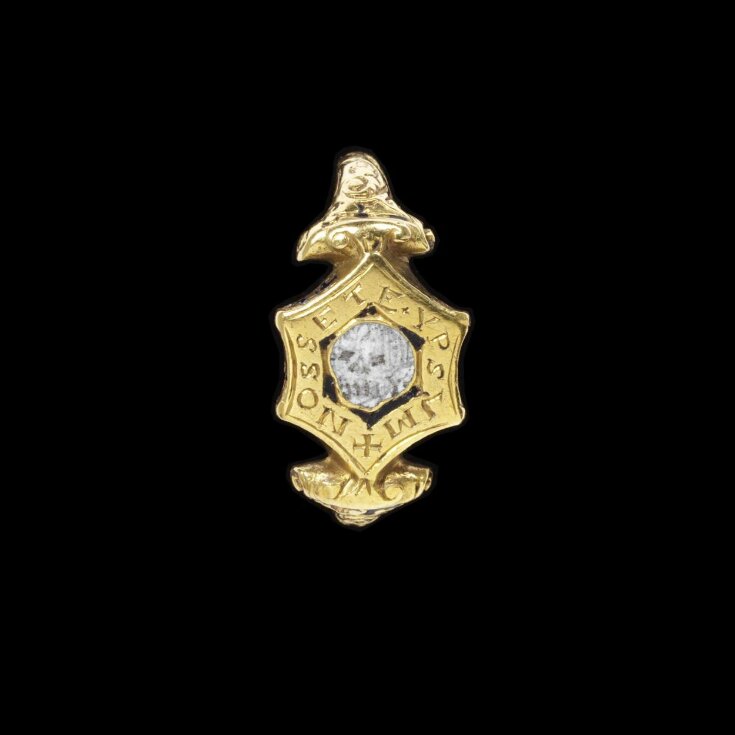

| Brief description | Enamelled gold ring, the hexagonal bezel enamelled with a skull and the inscription + NOSSE TE. YPSUM (Know yourself) and 'Dye to lyve' with volutes and foliated shoulders enamelled in black, England, about 1550-1600. |

| Physical description | Enamelled gold mourning ring, the hexagonal bezel with incurving sides, enamelled in white with a skull surrounded by the inscription + NOSSE TE. YPSUM and on the edge + DYE TO LYVE with volutes and foliated shoulders enamelled in black |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Object history | Ex Waterton Collection. The custom of wearing a memento mori ring was obviously well known in sixteenth century England. Shakespeare alludes to it when Falstaff urges Mistress Tearsheet not to speak like a death's head in Henry Iv (act II, scene 4) and in Love's Labour's Lost, Lord Biron compares the schoolmaster Holofernes to 'a death's head in a ring' (Act 2, scene 2). A less known play by Marston, The Dutch Courtesan, 1605, alludes to the fate of the courtesans thus: "As for their death, how can it be bad, since their wickedness is always before their eyes, and a death's head most commonly seen on their middle finger'. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | A devout Christian in sixteenth century Europe would be conscious of the fragility of life and the ever present threat of death, through disease, accident or if lucky, old age. Christians therefore felt the need to prepare their souls for everlasting judgment through prayer and reflection. 'Memento mori' (remember you must die) inscriptions and devices such as hourglasses, skulls, crossbones and skeletons became fashionable on many types of jewellery. A ring worn on the finger would be a daily reminder to prepare for life in the world to come. Rings decorated with this funereal imagery were also left in wills to family and friends. In the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the practice of bequeathing rings belonging to the deceased to friends and family was gradually replaced by the custom of leaving a sum of money to buy commemorative and mourning rings. Later in the seventeenth century, rings were distributed at the funeral service to be worn in memory of the deceased. The inscription on this ring reads: 'Nosse te psum', a variation on 'Nosce te ipsum' or 'know yourself', which was a popular motto on memento mori jewellery. In 1617, the will of Nicholas Fenay of Yorkshire describes a ring which was to be left to his son: 'having these letters NF for my name thereupon ingraved with this notable poesie about the same letters NOSCE TEIPSUM [sic know thyself] to the intent that my said son William Fenay in the often beholding and considering of that worthy poesye may be the better put in mynde of himselfe and of his estate knowing this that to know a man's selfe is the beginning of wisdom'. The inscription 'Dye to lyve' refers to the need to give up earthly life in favour of eternal life in Heaven. This ring forms part of a collection of 760 rings and engraved gems from the collection of Edmund Waterton (1830-87). Waterton was one of the foremost ring collectors of the nineteenth century and was the author of several articles on rings, a book on English devotion to the Virgin Mary and an unfinished catalogue of his collection (the manuscript is now the National Art Library). Waterton was noted for his extravagance and financial troubles caused him to place his collection in pawn with the London jeweller Robert Phillips. When he was unable to repay the loan, Phillips offered to sell the collection to the Museum and it was acquired in 1871. A small group of rings which Waterton had held back were acquired in 1899. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 920-1871 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | July 11, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest